By Arthur Cecil Perry and Gertrude A. Price in 1914

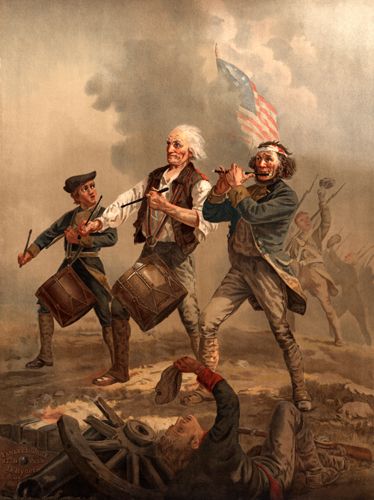

Battle of Princeton

The people, I believe, are as truly loyal as any subjects the king has; but they are a people jealous of their liberties, who, if those liberties should ever be violated, will vindicate them to the last drop of their blood.

— A member of the British House of Commons during a heated discussion concerning the British colonies in North America

~~

For more than a century, England had possessed thirteen colonies stretching along the coast between Canada and Florida. In 1763, by the treaty that followed the French and Indian War, her sway had been extended over the greater part of North America. Though England was immensely proud of the large territory her colonists had helped her to win from the French, she used strange means of showing her gratitude. Like the other leading nations of Europe, she believed that colonies were beneficial for trading. One reason why England maintained colonies was that she might sell goods to them at great profit.

The British Parliament made many laws that benefited the English merchants. For instance, if a prosperous Virginian wished to buy for his wife some shimmering silks from Paris, the law forbade him to send directly to France for them. He was allowed to purchase them only through English merchants, which added greatly to the cost. Again, although another country might be willing to pay him a better price for his tobacco and rice, England was the only land he was allowed to send them to. The colonists felt they were unfairly treated for these reasons and many others. Naturally, they began to do what they could to secure better conditions.

Even as early as 1676, a spirit of rebellion had appeared in Virginia. When the Indians killed several colonists, Governor William Berkeley was asked to take action, but he refused. It has been said that he was trading with these Indians and wished to keep on friendly terms with them. When they attacked the plantation of a young lawyer, Nathaniel Bacon, and killed his overseer, he asked the governor’s permission to punish the red men. The governor again refused.

Then, Bacon, with a party of young men as bold and vigorous as himself, marched against the Indians and punished them so severely that they troubled the colonists no more. But, because Bacon and his men had acted without permission, the governor declared them outlaws.

However, Bacon had the support of many of the colony’s people, and the governor was afraid of his power. For months, the two men waged a contest for government control. First, one and the other would gain possession of Jamestown, Virginia. Finally, Bacon destroyed the village by fire to ensure it would not again shelter the governor. When rebuilding time came, a better site was chosen. The new capital was known as Williamsburg. Bacon’s Rebellion was only one instance of trouble between the colonists and their governors. There were many other cases of dispute, which, however, did not lead to open revolt.

By 1750 England had passed many laws to encourage trade with her colonies. Some of the laws forbade them to trade with other countries or, in some cases, with one another. Had all these laws been rigidly carried out, the great Revolution might have come before it did.

Colonists Complain

But, they were not so enforced. The colonists were able to evade them in many ways. For example, they smuggled goods into the country and out, violating the laws. The royal governors made the best of it and pretended not to see what was happening. At the same time, they did many things that displeased the liberty-loving colonists. Sent over by the king, the governors felt and acted as though they had his power. But, the colonists regarded their Assemblies as having more authority than the governors. This, of course, angered the governors and the king.

While France was a power in America, England had seen that she must keep on good terms with her colonists, lest France steps in and win them over to her side.

After that danger was past, the English government thought it was quite a time to enforce the laws. It determined to stop the secret trading between the colonists and other countries. Customs officers were encouraged to search for smuggled goods.

This they could do by using warrants known as “writs of assistance.” Such a writ gave the officers the right to enter, in their search, any store or private residence. They could break down doors and open trunks on the mere suspicion that goods had been smuggled. The colonists were indignant. James Otis of Massachusetts argued eloquently against these writs of assistance, but the courts decided that such writs were lawful.

The French and Indian War had given the colonists new confidence in themselves. Fighting side by side, they had learned to respect one another. They had discovered that their men were good fighters and had able leaders, such as George Washington, John Stark, and Israel Putnam. They had lost both men and money in the war, but they gloried the loss because they were Englishmen fighting for England. At this time, the colonists were not anxious to be rid of their mother country. Far from this, they were true patriots asking for the rights of Englishmen.

However, this would begin to change when England decided to keep a standing army in the colonies for their protection and to force the colonists to bear a part of its cost. To help raise the needed money, the Stamp Act was passed. This law compelled the people to buy stamps that had to be placed on business contracts, legal papers, and newspapers. Some stamps cost but a penny or two; others, from twenty to fifty dollars.

The colonists were incensed, not because of the tax, but because of how it was levied and its purpose. One of the rights an Englishman holds most precious is that of being represented in the lawmaking body that decides upon the taxes. The Americans indeed had their own Assemblies, but they were not represented in Parliament, the English taxing body. And it was Parliament that had levied the Stamp Tax and had made other unsatisfactory laws for the colonists. Moreover, the colonists did not believe a standing army was needed in America during peace.

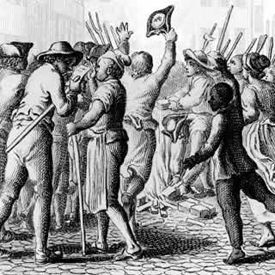

People in Boston greeted the Stamp Act as they would have greeted some great sorrow. The church bells were tolled, the flags were put at half-staff, and a storm of protest broke forth.

In New York, copies were made of the law, but a grinning skull appeared in place of the king’s coat of arms, usually printed on all legal papers. The people then destroyed boxes of the hated stamps and stamped paper and threatened the men appointed to collect the stamp tax. James Otis suggested that Congress be called to take action. Nine of the colonies sent delegates to this Congress, held in New York, and signed a petition sent to the king and Parliament.

After much debate, the Parliament saw they had made a mistake and repealed the Stamp Act. However, King George saw it differently. Not willing to listen to his advisers, he believed in showing the colonists “their place.” With his influence, Parliament passed several laws taxing the colonists in other ways, including duties on various imports such as glass, lead, paper, and tea. The levying of these taxes and the presence of British troops sent to the colonies caused further anger among the colonists.

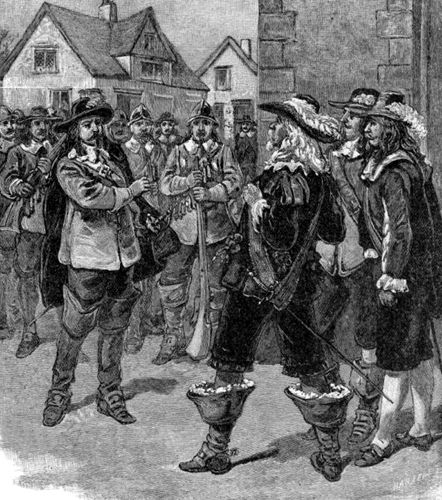

On January 17, 1770, British soldiers sawed down a “Liberty Pole,” which had been placed in what is now City Hall Park in New York City by the “Sons of Liberty,” a group of American Patriots. The pole, complete with banners, had been set up to celebrate the Stamp Act repealed in 1765. Two days later, the soldiers also began posting British handbills titled “God and a Soldier,” which attacked the Sons of Liberty as “the real enemies of society.” A man named Isaac Sears and several others tried to stop them. The group then captured some soldiers and marched his captives toward the mayor’s office. More colonists gathered, and when more soldiers arrived to disburse them, it resulted in a skirmish known as the Battle of Golden Hill. In the melee, several of the soldiers were severely bruised, and one had a severe wound. Some townsfolk were also wounded, and one had been fatally stabbed.

Two months later, On March 5, a similar clash occurred in Boston. That evening, when a party of boys taunted a British sentry in front of the custom-house door, a guard came out, and a crowd gathered. As the crowd grew larger, more people began to harass the soldiers, and in the end, shots were fired. Five civilians were killed and several wounded.

The resentment of the colonists grew. Throughout the country rang the bold words of Patrick Henry of Virginia: “Taxation without representation is tyranny!” The colonists refused to buy goods from English merchants until the taxes were repealed. This, in turn, called forth a protest from the merchants, who were rapidly losing money. But, the king’s party argued that if all the taxes placed upon the colonists were taken away, the colonists would feel they had won.

So another plan was adopted. Most of the taxes were removed, but a small tax on tea was retained. The tax was so small that it was cheaper for the colonists to buy their tea from England than to smuggle it from Holland and the English merchants were sure they would get back their trade.

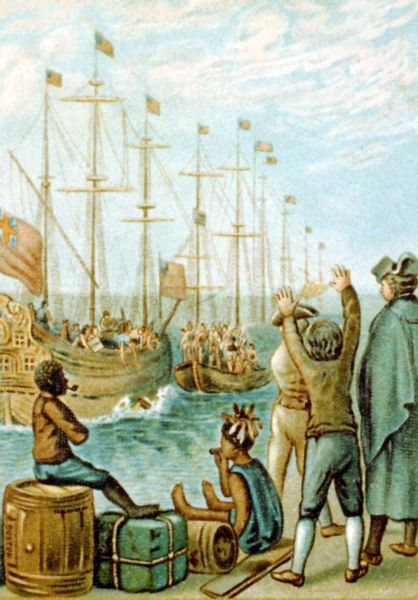

But, the Americans still refused to buy their tea, and when three shiploads came into the Boston harbor in the fall of 1773, the colonists decided to act. They warned the ship’s master that “it was at his peril if he suffered any of the tea brought by him to be landed.” They urged him to take his tea back to England. But the governor would not permit him to sail out of the harbor and kept warships on the watch to prevent his doing so.

On the morning of December 16, 1773, thousands of people gathered at a town meeting. “How will tea mingle with salt water?” someone hinted. The action was taken that very evening. At about nine o’clock, there rang through the quiet streets the war-whoop of Mohawk Indians. Fifty white Party men in Indian guise, hatchet in hand, rushed down to the wharf and boarded the ships. The tea chests were then opened, and their contents were thrown overboard into the sea.

The news of this daring spread to the other cities where tea had been sent — New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. The action of brave little Boston inspired them, and they, too, refused to buy the tea. Boston’s punishment came quickly. Her port was ordered closed until she should pay for the destroyed tea. This meant that nearly all her business was stopped, and she could not get supplies by sea. The English government thought that making an example of Massachusetts in this way would frighten the other colonies into submission. But, it was mistaken. The colonies felt that Boston was suffering for them all, so they loyally rallied around her and sent her supplies, accompanied by messages of courage. The women, in societies known as the “Daughters of Liberty,” pledged to wear homespun clothes and not drink tea.

On September 5, 1774, representatives from all the colonies, except Georgia, met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania at a meeting known as the First Continental Congress. Georgia did not send delegates as, at the time, they were seeking help from London in pacifying its smoldering Indian frontier. The 56 members met to consider their options, including an economic boycott of British trade, publishing a list of rights and grievances, and petitioning King George to redress those grievances. The delegates also called for a second meeting if their petition was unsuccessful in halting the enforcement of the Intolerable Acts.

When their appeal to the Crown had no effect, the Second Continental Congress was convened the following year, on May 10, 1775, to organize the colonies’ defense at the onset of the American Revolutionary War. The delegates also urged each colony to set up and train its own militia.

It had been but a month or two before that Patrick Henry had stood up in old St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, and cried, “We must fight. I repeat it, sir, we must fight. I know not what course others may take, but, as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

And he had voiced the feelings of the greater part of the colonists. For a long time, they had been working together to avoid war. Now, they had to work together to prepare for it.

Meanwhile, in all the towns, civilians secretly met at night, practicing and drilling so they might be ready for war at a minute’s notice. For this reason, they were called Minute Men. Further, preparations were made by storing away supplies such as powder, shot, and food.

Though all this was done secretly, Governor Gage of Massachusetts discovered that supplies were being stored at Concord. At about the same time, he received orders to arrest and send to England for treason, two of the leaders — Samuel Adams and John Hancock. But, neither Adams nor Hancock was to be found in Boston, and it was reported that they were in Lexington.

Governor Gage thought that if he could make a quick, unexpected dash for Lexington and Concord, he might succeed in capturing the men and the hidden stores. Accordingly, in the dead of night, on April 18, 1775, he sent British soldiers from Boston to secretly make their way to Lexington. But, the Americans had been warned by Paul Revere.

When the British arrived at Lexington the next morning on April 19, Adams and Hancock had gone, and the Minute Men were drawn up on the village green. The astonished English commander ordered the patriots to disperse, but they stood their ground. The commander drew his pistol and gave the order to fire. Eight Minute Men fell dead with the first volley, and ten more were wounded. The Revolutionary War had begun.

The British then continued their advance for Concord to get possession of the supplies. However, when the soldiers arrived, the supplies mysteriously disappeared. Still more surprising than the disappearance of the stores was the great number of Minute Men who guarded the city and drove back some 200 Redcoats from the Concord Bridge. As the British began their retreat to Boston, they were fired upon by patriots hiding in the bushes along the roadside.

The news of the war quickly spread through the colonies. On all sides came the call, “Minute Men to arms!” How this call was answered is well illustrated by the zeal of Israel Putnam, an old fighter of the French and Indian War. When a horseman galloped by his field, giving the cry to arms, Putnam rode quickly to Boston, where Minute Men had gathered from all parts of the colony.

In colonial days, Boston occupied only one of the several peninsulas the city now covers, and the British army was quartered on one. Across the channel was the village of Charlestown and, beyond it, Bunker Hill. The Americans saw that they would command Boston if they could fortify and hold this hill.

So, on the night of June 16, 1775, their men crept up the slope and set to work throwing up rude fortifications. When morning dawned, they stood in firm possession of the hill. The British realized that to keep Boston; they must dislodge the Americans from their position. They debated as to the best method of attack. Had they gone by sea to the rear of the hill, they might have been easily successful, but they decided to make a charge at the front.

The Americans had little powder, so their two commanders, General Putnam and Colonel Prescott, warned the men to wait until the enemy was close upon them. Up the hill marched the well-trained soldiers of England. Closer yet closer, they came, with no sign from the Americans.

Then, quick and sharp, came the order from behind the breastworks, “Fire!” A great volley broke forth, scattering the British and forcing them down the hill. Again they formed, and again they climbed the hill.

Again that death-dealing volley forced them back and down. A third time they tried. The American powder was nearly exhausted, yet the fearless defenders fought on with guns, stones, knives, and even their fists. But the British were too strong. The Americans were forced back, and the British held the hill. Putnam was disappointed. It seemed to him that the patriots should have held out longer after such gallant fighting, but others said that the defense that day was beautiful, even though it ended in defeat. Throughout the country, there was great rejoicing.

But, there were great difficulties ahead. An army was needed, but it was hard to get each colony to promise its share of men. To make matters more complicated, the new Congress was constantly bickering, which weakened its power and discouraged the people. They did make one very wise decision, however, that of appointing George Washington as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army. His remarkable military skill, already shown in the French and Indian War, and his high character made him a fitting leader in the great cause.

When told of his appointment, Washington said, “I beg every gentleman may remember it in this room, that, I this day declare, with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.” Despite his modest doubts, he would bring honor and glory to himself and his country.

Beneath a famous old elm tree at Cambridge, Massachusetts, on July 3, 1775, Washington, tall and dignified, first stood before the eager young soldiers and drew forth his sword as commander of the American Army. No one knew better than Washington the great task that was before him. The drilling of the soldiers until they were weary, the constant begging for supplies, which were so slow in coming, the petty quarrels among the soldiers themselves — all these difficulties, together with the great responsibility of the position, would have daunted most men.

Several great battles and hundreds of skirmishes would take place over the next eight years in the fledgling nation’s struggle for independence.

In April 1782, the British Commons voted to end the war in America, and preliminary peace articles were signed in Paris at the end of November 1782. However, the formal end of the war did not occur until the Treaty of Paris and the Treaties of Versailles were signed on September 3, 1783. The last British troops left New York City on November 25, 1783, and the United States Congress of the Confederation ratified the Paris treaty on January 14, 1784.

The total loss of life resulting from the American Revolutionary War is unknown, but it is estimated that some 25,000 American Revolutionaries died during active military service. Only about 8,000 of these deaths were in battle; the other 17,000 soldiers died from the disease. The number of patriots seriously wounded or disabled by the war has been estimated from 8,500 to 25,000.By Perry, G. Price, 1914. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

About the Article: This article on the American Revolution was, for the most part, written by Arthur Cecil Perry and Gertrude A. Price and included in a chapter of their book American History, published in 1914. However, the original content has been heavily edited, and additional information has been added.

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm, —

A cry of defiance and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

— Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Paul Revere’s Ride

Also See:

Paul Revere and His Midnight Ride

Causes of the American Revolution

Initial Battles for Independence

American History (main page)