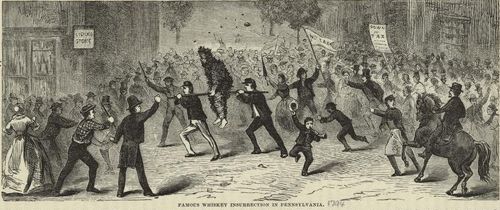

What started as a tax in 1791 led to the Western Insurrection, better known as the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, when protesters used violence and intimidation to prevent federal officials from collecting.

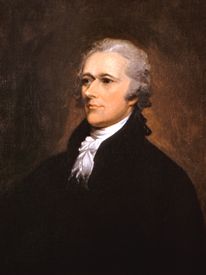

On March 3, 1791, Congress instituted a tax on distilled liquors to help pay off the debt from the American Revolution. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton had initiated a program to increase central government power, and the tax was to fund his policy of assuming the war debt of those states who failed to pay.

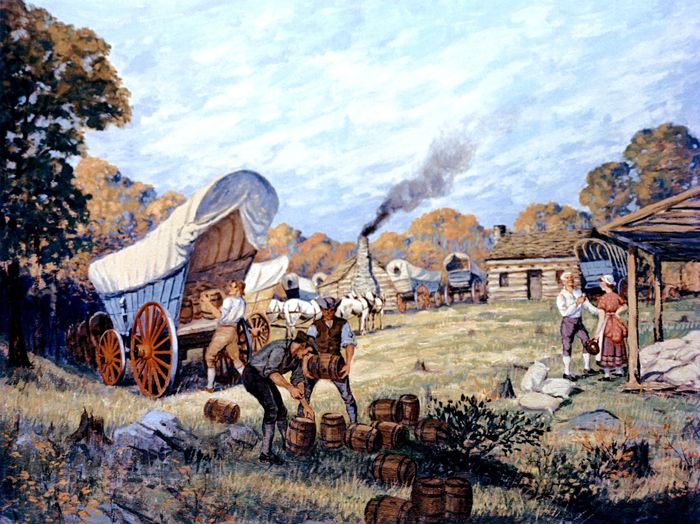

During this time, the Allegheny Mountains separated the western part of Pennsylvania from the east. Farmers, the majority of the population, found there was a limited market for their grain locally, and it was difficult to transport the grain to the east for sale. So, instead, farmers converted their grain to whiskey, which made it easier to transport and more marketable.

The excise tax, passed in 1791 on all distilled spirits, was based on the capacity of the still rather than the quantity of production. In addition, it was required to be paid in cash, which at the time was unusual since those in western Pennsylvania often used whiskey to pay for goods and services. The tax was also uneven in collecting it between small and large producers. Smaller still operations were required to pay the tax throughout the year at about nine cents per gallon. Larger producers in the east, who benefited from cheaper transportation costs, could decrease their tax by increasing their volume and were allowed to make annual payments that amounted to six cents per gallon.

The farmers of western Pennsylvania were already upset with the government over a lack of protection against Indian attacks. The tax just added to their frustration, and they felt that this direct interference by the government in their business was unjust and a violation of their rights. Many of them war veterans argued they were fighting for the principles of the American Revolution and taxation without local representation. This immediately led to organized resistance to the tax in the summer of 1791, with many farmers refusing to pay. Collectors were ambushed and humiliated, and some were even tarred and feathered.

The violence continued to escalate over the next several years and spread to other counties until it came to a head in the summer of 1794. Subpoenas were issued for over 60 distillers who had not paid the tax that May. Under the law, those served with the subpoenas were obligated to travel to Philadelphia to appear in federal court, which burdened those on the western frontier and beyond many of their means. So in June, Congress modified the law so that they could appear in local state courts, but by that time, U.S. Marshall David Lenox, under Alexander Hamilton’s direction, was already serving writs saying they had to come to Philadelphia. Over the years, historians have argued that Hamilton intentionally did not wait for the change in the law to serve the writs to provoke violence that would justify federal military intervention. Others have called it a string of ironic coincidences.

Regardless, Federal Marshal Lenox had served most of the writs without incident by mid-July. However, on July 15, Lenox and Federal Tax Inspector General John Neville were fired upon at the farm of Oliver Miller, about 10 miles south of Pittsburg. The men split up, with Lenox retreating to Pittsburgh and Neville returning home to Bower Hill. That next day, around 30 Mingo Creek militiamen showed up at Bower Hill demanding the surrender of Lenox, who wasn’t there. Neville responded by firing a shot from his fortified home, mortally wounding Oliver Miller. The rebels then retreated to Couch’s Fort for reinforcements. By the time they returned the next day, they had 600 men and were now commanded by Major James McFarlane, a Revolutionary War veteran.

Neville also had some reinforcements with 10 U.S. soldiers from Pittsburgh under the command of Major Abraham Kirkpatrick, who, before the rebels arrived, had Neville leave the house to a nearby ravine. In the meantime, Lenox and Neville’s son returned to the area but were captured by rebels. Historians say it is unclear how many casualties resulted, but after failed negotiations between the rebels and Kirkpatrick, shots were fired, and after an hour, rebel leader McFarlane called for a cease-fire. As he stepped into the open, a shot from the house killed him, which enraged the rebels, who then set fire to the house, forcing Kirkpatrick to surrender. Kirkpatrick, along with Lenox and Neville’s son Presley, were kept as prisoners but later escaped.

McFarlane’s death fueled rage among the rebels, whose leaders started urging more violent resistance. In late July, a group led by David Bradford robbed the U.S. mail as it left Pittsburgh so they could go through the letters and see who opposed them. Finding several, Bradford called for men to meet at Braddock’s field on August 1.

Some 7,000 showed up, many of them not even landowners nor distillers but upset over the tax and other economic issues. Much of the anger was directed at wealthy families without connection with the tax. There was even talk of declaring independence from the United States. Some plans included marching through Pittsburgh and looting and burning the homes of the wealthy. Luckily, this was defused by Pittsburgh citizens who banished several men who opposed the rebels and expressed support for the rebellion.

In the meantime, President George Washington was doing his best to confront the armed insurrection while maintaining positive public opinion. He decided to send a peace commission to meet the rebel committee, but at the same time, he tried to raise a militia through the states. Hamilton, writing under the name of “Tully” in Philadelphia newspapers, denounced the mob violence in western Pennsylvania and advocated military action.

On August 7, 1794, Washington issued a proclamation stating that, with the deepest regret, the militia would be called to suppress the rebellion. He called for the rebels to disperse by September 1. Enacting the Militia Act of 1792, which allowed the President, with Federal court approval, to use State militiamen for instances like this, letters were sent to governors of Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia requesting almost 13,000 men. This also caused problems as few men volunteered, and a draft was used to fill the ranks. Protests and riots, along with draft evasion, were widespread.

In a last-ditch effort to avoid confrontation, the peace commission, consisting of Attorney General William Bradford, Pennsylvania Senator James Ross, and Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Jasper Yeates, met with rebels for several days in late August and early September. After the talks failed, they reported back on September 24 that it was “absolutely necessary that the civil authority should be aided by military force to secure a due execution of the laws.”

During this time, Washington’s militia of 13,000 were gathered at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. On September 19, President Washington began leading the troops on a nearly month-long march west over the Allegheny Mountains to the town of Bedford. On September 25, after getting the report from the peace commission, Washington issued a proclamation that he would not allow “a small portion of the United States dictate to the whole union.” He called on all citizens not to aid the rebels. Washington remains the only sitting President to lead troops in the field personally. After getting them to Bedford, Washington returned to Philadelphia, placing General Henry Lee in command. Alexander Hamilton also remained with the troops.

In late October, the Federalized militia began entering the western counties of Pennsylvania, and the rebel organization began falling apart. By mid-November, 150 rebels, including 20 of its leaders, had been arrested. On November 29th, under the direction of President Washington, General Lee issued a general pardon for all but 33. Of those, only a few were tried, and two were convicted, who were also later pardoned. President John Adams would later pardon David Bradford in 1799. Bradford had escaped to Spanish-controlled New Orleans.

While the physical and violent opposition to the tax was over, the political opposition continued. That opposition would help Thomas Jefferson defeat President Adams in the 1800 election. In 1802, Congress repealed the distilled spirits excise tax and all other internal Federal taxes, relying solely on import tariffs for revenue, which were growing along with the nation’s foreign trade.

The Whiskey Rebellion is significant in American history because it was the first test of federal authority in the United States and enforced the idea that the newly formed government had the right to levy taxes that would impact citizens in all states. It also enforced the right of the government to pass laws impacting all states.

©Dave Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

American History Photo Galleries

Sources:

U.S. Department of the Treasury – Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau

Library of Congress

Wikipedia