Commonly called America’s Second War of Independence, the War of 1812 was a major conflict with Great Britain in the early years of the nineteenth century. Unlike the American Revolution, the causes of the War of 1812 were far more economically and politically motivated than idealistic.

Instead, the War of 1812 pitted the fledgling United States, barely twenty years old, against Great Britain in a conflict centered on recognizing American commercial and political rights. Specifically, the reasons included trade restrictions brought about by Britain’s ongoing war with France, the impressment of American merchant sailors into the Royal Navy, British support of American Indian tribes against American expansion, and outrage over insults to national honor after humiliations on the high seas.

The signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 ended the Revolutionary War and established the United States among the world’s nations. The treaty, however, neither guaranteed the new nation’s survival nor ensured that the powers of Europe would respect its rights. In upholding its rights to trade freely with all of the world’s countries, the United States government struggled to balance military preparedness and diplomacy. The prolonged wars between Britain and France (1793-1815), kicked off by the French Revolution, greatly complicated America’s ability to protect the rights of its shipping and sailors. Additionally, many Americans along the nation’s western frontier believed that the British in Canada encouraged Indian raids on their settlements.

After the American Revolution, the United States sought to insulate itself from European affairs and build up the new nation. George Washington, in his Farewell Address of 1796, laid out this policy of American neutrality in European affairs:

“The great rule of conduct for us, regarding foreign nations, is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence, therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves, by artificial ties, in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities.”

However, this would prove to be impossible, as the French Revolution sent Europe into political upheavals. Both the British and the French expected American support during the war and would not accept American neutrality in the matter. Both sides attacked and impounded American shipping, trusting that the United States Navy could not respond effectively to this violation of American neutrality.

The British, confident that the American experiment in democracy was doomed to failure, continued to harass American merchantmen and impress American seamen. Desperate for sailors to man their warships, British captains increasingly boarded American ships and “impressed” or forced sailors into service, claiming that the merchant seamen were deserters from the Royal Navy. In the meantime, British agents in North America supported insurrections by Native American tribes against the United States government in the Old Northwest. America’s efforts to preserve its neutral rights by stopping all trade with the warring powers had no effect other than to hurt the U.S. economy.

At the same time, the American alliance with the French, dating back to the American Revolution, was beginning to unravel. The first forts built in the United States, beginning in the 1790s, were designed and overseen by French military engineers. However, with the French Revolution and the United States’ neutral stance, the alliance was soon tossed aside. Attacks by the French on American shipping led to an undeclared naval war from 1798 to 1801, known as the Quasi-War. When war between Britain and France started again in 1803, Britain forbade neutrals, including the United States, from trading with France and her allies. Many Americans believed Britain’s measures were an attempt to re-impose colonial status on them.

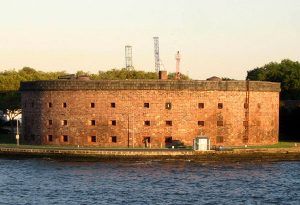

With the breakdown with the French, the United States badly needed to design and build its own fortifications, and Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Williams, the commandant of the Army Corps of Engineers and the superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point, was assigned the task. Williams was a relative of Benjamin Franklin’s. While Franklin spent the American Revolution in Paris negotiating the French alliance, Williams studied military engineering from the same engineers who would soon become America’s enemies. Full of these ideas, Williams was selected to improve American coastal fortifications in the years leading up to the War of 1812. From 1807 to 1811, Williams designed and completed the construction of Castle Williams and Castle Clinton in New York Harbor.

After all the diplomatic issues with Great Britain, from preventing trade to impressing sailors, the United States declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812.

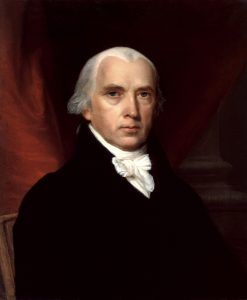

President James Madison’s war message to Congress echoed the language of the Declaration of Independence. Less than a month later, Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Williams resigned from the Army in July 1812 because the Secretary of War, William Eustis, refused to give him command of Castle Williams. At that time, the State of New York appointed Williams in charge of constructing fortifications for New York City.

Although the outbreak of the war had been preceded by years of diplomatic disputes, neither Britain nor the United States was prepared. Britain was heavily engaged in war with the French, and in the United States, the military was understaffed, and the government did not have the money to finance the war adequately. President Madison assumed that the state militias would quickly seize Canada and that negotiations would follow. However, from the beginning, the war was highly unpopular, especially in New England, which would later make threats of secession.

The U.S. Army, consisting of fewer than 12,000 men, was not nearly enough to achieve Madison’s goals. Congress authorized the expansion of the army to 35,000 men; however, the service was voluntary, offered poor pay, and few trained and experienced officers. Britain exploited these weaknesses, blockading only southern ports for much of the war and encouraging smuggling.

On July 12, 1812, General William Hull led a force of about 1,000 untrained, poorly-equipped militia across the Detroit River. He occupied the Canadian town of Sandwich (now a neighborhood of Windsor, Ontario). By August, Hull and his troops, which had increased to about 2,500 men, quickly withdrew to the American side of the river after hearing the news of the capture of Fort Mackinac by the British. In Detroit, he also faced unfriendly Native American forces, which threatened to attack. Hull surrendered Fort Detroit to Sir Isaac Brock on August 16, 1812. The surrender cost the United States the village of Detroit and control over most of the Michigan territory.

Numerous battles and skirmishes would be fought over the next two years while the United States suffered critically without proper leadership. This un-preparedness eventually drove United States Secretary of War William Eustis from office in January 1813, though military and civilian leadership remained a critical American weakness until 1814.

When the government turned to building warships on the Great Lakes, things began to improve. Recruiting some 3,000 men, 11 warships were built on Lake Ontario, and in 1813, the Americans won control of Lake Erie and cut off British and Native American forces in the west from their supply base. On October 5, 1813, the Americans attacked and won a victory over the British and Native Americans at the Battle of the Thames in Ontario, Canada. During the battle, Shawnee Chief Tecumseh was killed, and his Indian coalition disintegrated.

The powerful Royal Navy blockaded much of the coastline at sea, though it allowed exports from New England, which traded with Canada in defiance of American laws. The blockade to the south devastated American agricultural exports, but it helped stimulate local factories that replaced previously imported goods. Though the Americans fought valiantly against the British on the coastline, their small gunboats were no match for the Royal Navy.

The British raided the coast with several successful attacks on the eastern ports and cities, including the burning of the White House, the Capitol, the Navy Yard, and other public buildings, in the “Burning of Washington.” Britain’s success in Washington led them to levy “contributions” on bayside towns in return for not burning them to the ground. It also resulted in U.S. Secretary of War John Armstrong being dismissed.

After Napoleon abdicated in April 1814, the British were able to send their armies to the United States in full force; but, by that time, the Americans had learned how to mobilize and fight. The Treaty of Ghent, the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812, was signed on December 24, 1814, restoring relations between the two nations with no loss of territory. Because of the era’s slow communications, it took weeks for news of the peace treaty to reach the United States. As a result, the Battle of New Orleans was fought in January 1815, where General Andrew Jackson defeated the British. The victory made Jackson a national hero, restored the American sense of honor, and ruined the Federalist party’s efforts to condemn the war as a failure.

In military terms, the War of 1812 was inconclusive, though the United States benefited when Britain ended trade restrictions and the impressment of American sailors. The three-year conflict also resulted in an upsurge in American nationalism, increased funding of the peacetime military, better coastal defenses, a more secure western frontier, and a final confirmation of the American Revolution’s outcome. At the war’s conclusion, a French diplomat commented that “the war has given the Americans what they so essentially lacked, a national character.”

Though considered one of America’s “forgotten wars,” the War of 1812 is preserved in the National Park System in areas as diverse as Fort McHenry National Monument in Maryland, Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial in Ohio, George Rogers Clark National Historical Park in Indiana, as well as Gulf Islands National Seashore along the coast of Mississippi and Florida, and Cumberland Island National Seashore in Georgia.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Source: National Park System

Also See:

Andrew Jackson – Dominating American Politics

American History (main page)

American Wars and Military Photo Print Galleries