Nathan Hale Statue

By Inez Nellie Canfield McFee in 1913

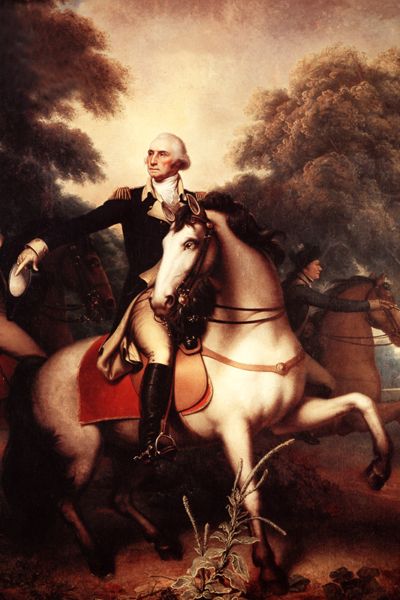

After his defeat in the battle of Long Island, New York, on August 27, 1776, George Washington was greatly troubled about what he should do. He had withdrawn his forces to New York City, but he knew not whether it was wiser to stay and defend the city or to fly to a place of greater security. The outlook was dark indeed. A fourth of the army was sick; a third had no tents, and many, chiefly new recruits, were short of clothing, shoes, and blankets. Altogether the patriot army numbered only 14,000 men fit for duty, scattered along a distance of 12 or more miles.

The British army of 25,000 brave and well-trained veterans lay encamped in front of them along the shores of New York Bay and the East River. Moreover, the British had a large fleet of warships lying at anchor and ready for service while spy ships sailed about continually, watching every movement of the Americans.

General George Washington

Winter was not far away, and Washington feared the effect upon the patriot cause if no effort was made to attack the British, yet it must be made in the face of almost certain defeat. His raw, suffering troops had little chance against twice the number of British regulars. What should be done?

Washington’s headquarters were in the home of Robert Murray, a Quaker merchant, and here he called his officers together to consider the grave and perplexing question. It had just been decided to move northward to Harlem Heights — a position much stronger than New York, as it allowed for a more open line of retreat if that were necessary, for Washington had no intention of being surrounded on Manhattan Island for the winter by the King’s forces, or, more probably, of losing his entire army in one swoop — when scouts came hurrying with the news that the British seemed to be getting ready to move. But no one knew where they were going.

“Gentlemen,” said Washington, “the fate of our army depends upon our finding out the enemy’s plans at once.” As all agreed, it was determined to send a spy into the British camp to pick up all the information he could find.

Washington entrusted the matter of finding the right man to Colonel Knowlton, one of his aids, who had greatly distinguished himself on many occasions. It proved to be a difficult task. All who were capable of filling the part shrank from it. At last, Colonel Knowlton thought of a clever scout who had undertaken many daring deeds and was noted for his rashness and bravery. He was sent for, but the dangerous task was too much even for him. The penalty, if captured, was too dreadful to contemplate.

“No, Colonel Knowlton,” he said firmly, “I am willing to serve my country in any honorable way. I will take any risks as a scout or fight the redcoats anywhere, but, sir, I cannot be a spy, even for General Washington, much as I respect and admire him.”

This seemed to be the sentiment of all. Colonel Knowlton was about to give up the search when he was startled by a low, firm voice at his elbow: “I will go. A soldier should never consult his fears when duty calls.”

He turned in surprise. The voice was that of Captain Nathan Hale, a brilliant young officer scarcely recovered from a severe illness. Hale’s friends pleaded with him not to go. It was madness, they said, for one whose prospects were so brilliant to undertake so dangerous a mission. But Hale was not to be dissuaded, for he did not consider the value of his life where his country’s needs were concerned.

“I wish to be useful,” he said, with a kindling face and eyes alight with the fire of patriotism, “and the mission is not without honor since it involves the fate of the army. My country’s claims are willful, and I am glad of this opportunity to serve her.”

Nathan Hale was Captain of a company of Connecticut volunteers. His men fairly worshiped him. He was the steward of their rations, clothing, and money and the sympathetic confidant of every lad in his regiment. He was a careful student of military tactics and often served on picket duty. But, despite all this, he found time to arrange wrestling matches for his men, to play ball and checkers, and, on Sundays, to hold open-air religious services.

He was born in a little old-fashioned house in Coventry, Connecticut, on June 6, 1755. Eight brothers and three sisters made the home a bright and joyous place. Both father and mother were people of sterling worth. Mr. Hale governed his family in a strict Puritan fashion, fearing the Lord. He was very loyal to his country, and after the war began, all the wool raised on his farm was made into blankets for the army. Three of his sons he dedicated to the ministry. Nathan was one of these.

As a lad, young Hale was bright, active, and passionate about all boyish sports. He liked books and read with interest everything that came his way. He entered Yale College at age 15 and graduated in 1773, just two years before the Battle of Bunker Hill. Shortly afterward, he entered the career of “schoolmaster” and was later elected principal of a select school in New London, not far from his hometown.

Professor Hale was well-liked by all his pupils. He earnestly sought to implant the principles of courage, manliness, and patriotism in their minds. On the playground, as well as in the schoolroom, he was their leader. No one was a better wrestler or ballplayer.

Battle of Lexington, April 19, 1775. illustration by John H. Daniels & Son, 1903.

When news came of the bloodshed at Lexington, young Hale was fired with enthusiasm. That evening, he attended a rousing mass meeting and was among the most ardent speakers. “Let us march at once,” he cried, “and never lay down our arms until we obtain our independence!”

A company was formed at white heat and marched for Cambridge the next day. The same promptness and dispatch marked his conduct after accepting Washington’s mission. Within a few hours, he had taken leave of his friends and, in company with one of his trusted soldiers, lay in wait for an opportunity to cross Long Island Sound. This was an impossibility in the vicinity of Harlem because of the British spy ships patrolling the Sound. So Hale and his companion crept stealthily along the Connecticut side until Norfolk was reached — a distance of 50 miles. Here a sloop was found to carry Hale across to the other side.

En route, he changed his uniform for a suit of citizen’s clothes and landed on Long Island as a schoolmaster searching for a school. Of course, he “accidentally” stumbled into a British camp and at once began to make friends with the dragoons, who, as Hale was a likable young fellow, he received him warmly.

Thus two weeks passed away. Hale journeyed from one point to another, constantly keyed to the highest pitch and scarcely sleeping at night. He was anxious to note everything that might serve the American cause.

At last, his mission was completed. He had made the rounds of the British camps and returned to his starting point, unharmed and unsuspected. He had learned all that his General desired and more and had his drawings and notes carefully concealed in the soles of his shoes. It seemed as if he was going to get home in safety. Perhaps this fact made him the least bit careless. He was exhausted and hungry, and, feeling that no one would recognize him in the schoolmaster’s garb, he ventured boldly into a tavern kept by a woman nicknamed “Mother Chick” that was the favorite loafing place of all the Tories in the vicinity. Hale should have been wise enough to avoid such a place, but the goal was so near that our hero felt no fear. He ate a good supper and spent the night at the tavern.

Bright and early next morning, Hale was up and secretly on the lookout for the boat he expected to meet him. Suddenly old Mother Chick burst into the room, crying, “Look out, boys! A strange boat is heading close in shore!” The Tories scattered like wildfire, and Hale carefully reconnoitered. It was not exactly the spot where he had arranged to meet his friends, yet it looked very much like the sloop, so he hastened down to the beach.

It was not the boat he expected, but he did not realize his mistake until he was too close to retreat, with six British marines pointing their muskets straight at him and crying, “Surrender or die!” ringing in his ears. Escape was impossible, and poor Hale was forced to give himself up almost in sight of victory! But he did it bravely and unflinchingly, as he became a true and noble soldier, and the British captain and sailors could but admire him. When young Hale was brought before General Howe, he looked him fearlessly in the eye and bravely owned that he was an American officer. He said he was sorry that he could not serve his country better. Without trial, the British General condemned him to die the death of a spy.

Poor, brave boy! How cruelly brief was the time left to him. Yet he took the sentence as calmly and nobly as he had the capture, but this time no words of sympathy came from the heart of his captor. He was unfeelingly turned over to Cunningham, the brutal provost marshal, and confined, under a strong guard, in the greenhouse at the rear of the mansion where Howe had his headquarters.

Here he spent the night alone, denied by his heartless keeper even the Bible he had asked for, but morning found him calm and ready. At the last moment, while preparations for his execution were being made, a young officer, moved by Hale’s noble bearing, kindly allowed him to sit in his tent long enough to write brief farewell messages to his mother and sweetheart. These were passed to Cunningham to be sent. After reading these sacred letters, the brutal officer tore them into shreds before his captive’s eyes, declaring that the “rebels should never know they had a man who could die so bravely.”

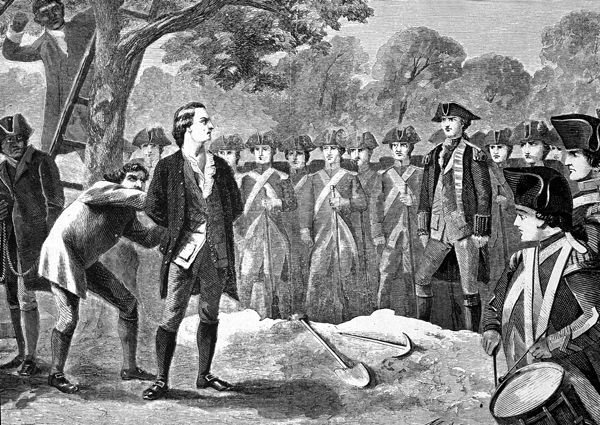

Just before sunrise on September 22, 1776, on a lovely Sabbath morning, Nathan Hale was led out to die. Early as it was, several men and women had gathered about the apple tree to serve for a gallows. This, perhaps, excited the provost marshal to more than his usual show of cruelty, for as the doomed youth mounted the ladder, he bawled coarsely, “Give us your dying speech, you young rebel!”

Nathan Hale paused where he was and, lifting his eyes to heaven, said in a clear, steady voice, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

So perished Captain Nathan Hale, the earliest martyr in the cause of American freedom. He gave his life fully and freely to his beloved country, thereby winning immortal fame. More than a century later, a handsome statue was erected to his memory in New York City. It stands in City Hall Square, one of the busiest spots of the metropolis, where he made his great sacrifice.

By I.N. McFee 1913. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated August 2023.

About the Author: This article was written in 1913 by Inez Nellie Canfield McFee and included in her book American Heroes From History. McFee also authored several other books on American History, poetry, birds, and more. The article as it appears here, however, is not verbatim as it has been edited and includes some additional information.