I have never, on the field of battle, sent you where I was unwilling to go myself; nor would I now advise you to a course which I felt myself unwilling to pursue. You have been good soldiers; you can be good citizens.

— General Forrest’s farewell address to his troops, Gainesville, Alabama, May 9, 1865

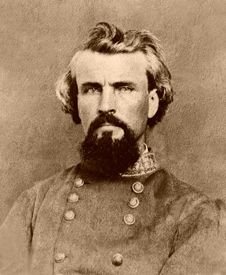

Nathan Bedford Forrest was a wealthy plantation owner who distinguished himself in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. A cavalryman, he saw extensive service in the Western Theater and became one of the most feared Confederate officers in the region. He was a master of mobile warfare and is often remembered for his fast attacks and raids.

Born to a poor Scots-Irish family in Chapel Hill, Tennessee, on July 13, 1821, Forrest was the first of twelve children. His father died when he was 17, and the ambitious young man soon pulled his family out of poverty, becoming a business and plantation owner and a slave trader in Mississippi. By the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, he had become one of the wealthiest men in the South.

Although his status as a significant planter exempted him from service, Forrest enlisted in the Confederate Army as a private, joining the Tennessee Mounted Rifles in June 1861. When he began to buy horses and equipment for the regiment, using his own money, he gained the attention of the “higher-ups,” who were surprised he enlisted. They commissioned him Lieutenant Colonel and tasked him to recruit and train a regiment of mounted rangers, Forrest’s Tennessee Cavalry Battalion. That October, he was given command over the 3rd Tennessee Calvery.

Though he had no formal military training or experience, he quickly proved himself to be an exemplary officer, first distinguishing himself in the Battle of Fort Donelson, Tennessee, in February 1862, where he refused to capitulate with the rest of the Confederate forces and made his way out before the fort was surrendered. That helped earn him Colonel in March of 1862 over the 3rd Tennesee Calvery, which he led in the April Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee. Forrest suffered the first of several battle wounds during the war here. Several months later, in July, he was promoted to Brigadier General and took part in the Confederate Heartland Offensive, leading his battalion in the Battle of Murfreesborough, Tennessee.

In December 1862, Forrest’s veteran troopers were reassigned by General Braxton Bragg to another officer against his protest. As a result, Forrest had to recruit a new brigade composed of about 2,000 inexperienced recruits, most of whom lacked weapons. Again, General Bragg ordered a raid into west Tennessee to disrupt the communications of the Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant. They were threatening the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Forrest protested that sending such untrained men behind enemy lines was suicidal, but Bragg insisted, and Forrest obeyed his orders.

In the raid, he showed his brilliance, leading thousands of Union soldiers in west Tennessee on a “wild goose chase” to try to locate his fast-moving forces. Never staying in one place long enough to be attacked, Forrest led his troops in raids as far north as the banks of the Ohio River in southwest Kentucky. He returned to his base in Mississippi with more men than he had started with. By then, all were fully armed with captured Union weapons. As a result, Union General Ulysses S. Grant was forced to revise and delay the strategy of his Vicksburg Campaign. A friend of General Grant’s was quoted as saying of Forrest, “He was the only Confederate cavalryman of whom ant stood in much dread.”

Forrest continued to lead his men in small-scale operations until April 1863, when he was dispatched into the backcountry of northern Alabama and west Georgia to defend against an attack of 3,000 Union cavalrymen commanded by Colonel Abel Streight, who had orders to cut the Confederate railroad south of Chattanooga, Tennessee, cut off Bragg’s supply line, and force Bragg and his troops to retreat into Georgia. With a force far smaller than those of the Union, Forrest and his troops chased Streight’s men for 16 days, harassing them all the way. On May 3, Forrest caught up with Streight’s unit east of Cedar Bluff, Alabama. Though his men were much fewer, he repeatedly paraded some around a hilltop to appear like a more significant force and convinced Streight to surrender his 1,500 exhausted troops.

Forrest served with the main army at the Battle of Chickamauga, Georgia, in September 1863 and took hundreds of Union prisoners. Like several others under Bragg’s command, he urged an immediate follow-up attack to recapture Chattanooga, which had fallen a few weeks before. When Bragg failed to do so, the two got into a confrontation, and Bragg reassigned him to an independent command in Mississippi.

On December 4, 1863, Forrest was promoted to major general. He would continue to lead his troops in more battles, including Paducah, Kentucky, Brice’s Cross Roads in Mississippi, where he defeated a superior Union force, and conflicts at Spring Hill, Franklin, Fort Pillow, and Nashville, Tennessee. By February 1865, he had been promoted to Lieutenant General.

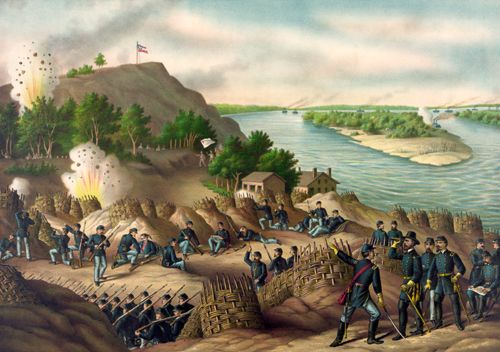

Fort Pillow Massacre, Tennessee

In his strategies and tactics, Forrest was often described as a “born military genius.” However, one blemish on his record was the Massacre of Fort Pillow, Tennessee, on April 12, 1864. In keeping with Confederate policy, Forrest ordered his troops to “take no more Negro prisoners” when they assaulted and captured Fort Pillow. A Congressional investigation committee verified the slaughter of more than 300 black men, women, and children within the fort.

He was forced back at Selma, Alabama, in April 1865 and surrendered his entire command in May. During the war, he was one of the most highly regarded cavalry and partisan rangers and one of the most innovative and successful generals. Modern soldiers still study his tactics of mobile warfare.

After the war, Forrest settled in Memphis, Tennessee, but was financially ruined due to abolishing slavery. Eventually, he took a job with the Marion & Memphis Railroad, where his business skills soon placed him in the position of President. At this time, the Ku Klux Klan movement was forming, and by 1867, he was made its first Grand Wizard. This choice and allegations of brutality in the Battle of Fort Pillow led to Forrest’s heroic reputation suffering dramatically. However, in 1869, Forrest, who disagreed with the increasingly violent tactics of the Ku Klux Klan, ordered it disbanded. Though the order was ignored, Forrest distanced himself from the organization.

In October 1877, he died from complications of diabetes and was buried at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis. In 1904, his remains were moved to Forrest Park, a Memphis city park.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Also See: