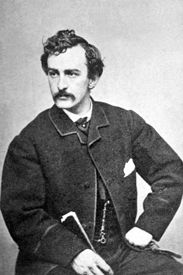

John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth loved acting but was even more passionate about his politics, leading to one of the darkest days in American History and the loss of a beloved President.

Born May 10, 1838, into the prominent Booth family of Maryland, he was the ninth of ten children whose father was Junius Booth, a famous and eccentric actor. Junius, who was estranged from his wife in England, came to the U.S. with his mistress, John’s mother, Mary Ann Holmes, in 1821. Junius wouldn’t officially marry Holmes until John’s 13th birthday in 1851.

John was athletic, popular as a boy, and skilled in horsemanship and fencing. John attended an Episcopal military academy in Catonsville, Maryland, when his father made him legitimate by marrying Holmes. However, he left school at the age of 14 after his father’s death.

A couple of years later, at age 16, Booth gained interest in the theatre and politics. Looking to follow in the acting footsteps of his father and older brothers Edwin and Junius Jr., John began practicing formal speaking daily and studied Shakespeare. He also became a young delegate to a rally for the ‘Know-Nothing Party’ anti-immigrant candidate Henry Winter Davis in his congressional run of 1854.

By the time he was 17, he made his own stage debut in Baltimore, appearing in Richard III. His performance did not go well, but he kept at it, acting at Baltimore’s Holliday Street Theatre, a frequent stage for the Booth’s. In 1857, he joined the Arch Street Theatre stock company in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and played a full season. By 1858, he was a stock company actor at the Richmond Theatre in Virginia, performing in 83 plays that year. Reportedly, his favorite role was that of Shakespeare’s Brutus, the slayer of a tyrant.

With his athletic build and romantic personal attraction, Booth was a hit with the ladies. By the end of the 1850s, he was already becoming famous and wealthy, earning $20,000 a year. During this time, Booth kept active in politics and, as an ardent supporter of slavery, joined a Virginia Company that aided in the capture of John Brown after his raid at Harpers Ferry. Booth was an eyewitness to Brown’s execution.

In 1860, Booth’s acting career took him on a tour of the Deep South, where he was widely acclaimed. At the same time, his anger toward the newly elected President Abraham Lincoln grew. After the Civil War began in 1861, he would smuggle medicines to the Confederacy during his travels. His entire family did not share Booth’s hatred for the Union and Lincoln, and John wound up feuding with his brother Edwin, who refused to make stage appearances in the South.

Booth was also outspoken about his admiration for the South, which did not play well with audiences in New York. Some citizens called for his arrest for treasonable statements. This did not seem to hamper reviews from critics, however, who continued to praise him as “the most promising young actor on the American stage.”

In 1863, Booth was arrested in St. Louis while on tour after he was heard saying he wished the President and the whole government would go to hell. He was charged with treasonous remarks against the government but was released after taking an oath of allegiance to the Union and paying a substantial fine. Later that year, family friend John T. Ford opened Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., where John was one of the first leading men to appear on stage. During a performance attended by President Lincoln, Booth is said to have shaken his finger at the President as he delivered a line of dialogue.

In November of 1864, Booth would perform for the only time with both his actor brothers, Edwin and Junius Jr., in a single benefit performance of Julius Caesar in New York. This time, he played Mark Anthony, with his brother Edwin playing Brutus, in a performance acclaimed as the greatest theatrical event in New York history. The proceeds from the event paid for a statue of William Shakespeare in Central Park, which still stands today.

John Wilkes Booth and brothers Edwin and Junius in the play Julius Caesar in 1864

That same month, President Lincoln was re-elected, filling Booth with more rage. In a letter to his mother leading up to the election, Booth wrote, “I have begun to deem myself a coward and to despise my own existence”. In fact, Booth had already begun to formulate plans to kidnap Lincoln and smuggle him to Richmond. Booth’s plans called for the President to be exchanged for Confederate prisoners and, in Booth’s mind, help bring the war to an end by emboldening opposition to the war in the North or forcing Union recognition of the Confederate government.

While no exact proof exists that Booth was acting as a Confederate Spy, some historians insist he was. They point to a trip Booth made in October 1864 to Montreal, then a center for clandestine Confederate activity. He reportedly spent ten days in the city, staying for a time at St. Lawrence Hall, a known rendezvous point for the Confederate Secret Service.

Lincoln won re-election on a platform advocating the abolishment of slavery through the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which prompted Booth to devote increasing energy and resources to his plan. He brought Southern sympathizers into the plot, including David Herold, George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell (a.k.a. Lewis Payne), and John Surratt, a rebel agent. John also began fighting more with his brother Edwin, who finally told him he was no longer welcome at his home in New York. Of Lincoln, Booth would tell his sister, Asia, “That man’s appearance, his pedigree, his coarse low jokes and anecdotes, his vulgar similes, and his policy are a disgrace to the seat he holds. He is made the tool of the North to crush out slavery.” Asia would write later that as a Union victory became more certain in 1865, Booth would go into wild tirades over Lincoln.

That February, Booth became secretly engaged to Lucy Hale, the daughter of U.S. Senator John Hale of New Hampshire. Unaware of his deep hatred for Lincoln, Hale invited John to Lincoln’s second inauguration on March 4. His co-conspirators were also in the crowd, but no attempt was made against the President. Later, Booth would remark about his excellent chance to kill the President if he had wished. An attempt to kidnap Lincoln later that month failed when the President’s plans changed, taking him away from a stretch of road where Booth and his men were waiting.

After Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, Booth’s kidnapping plan was mute. He reportedly told a friend of John Surratt that he was done with acting and that the only play he wanted to present was Venice Preserv’d. Though the meaning was lost to Surratt’s friend, the play he referred to was about an assassination plot.

On the morning of Good Friday, April 14, while Booth was at Ford’s Theatre getting his mail, John Ford’s brother told him that Lincoln and his wife, along with General and Mrs. Ulysses Grant, would be attending the play “Our American Cousin” that evening. Booth immediately gathered his co-conspirators with plans of assassinating not only the President but also General Grant, Secretary of State William Seward, and Vice President Andrew Johnson. His hope was to throw the Union into chaos by decapitating the Government, thus allowing the Confederate government to re-organize, or at the least avenge the South’s defeat.

Booth’s plan came together that evening, with his cohorts assigned to kill Seward and Johnson, while he would go to Ford’s theatre to kill the President and General Grant. Lewis Powell went to take out Seward, who was bedridden due to a carriage accident. Powell stabbed Seward, but the Secretary of State would survive. Meanwhile, Atzerodt, who was to assassinate Vice President Johnson, lost his nerve and wound up drinking all night, never making an attempt. General Grant changed his plans and would not attend the play with the President that night, instead of leaving Washington D.C. to visit relatives in New Jersey. However, the President and First Lady kept their plans for the Ford Theatre, which Booth had full access to due to his relationship with John Ford.

Around 10 p.m. that evening, as the play progressed, Booth slipped into the theatre’s Presidential Box and shot the President in the back of the head. Major Henry Rathborne, who was with the President, lunged at Booth, but John stabbed him, then jumped from the box to the stage and shouted “Sic semper tyrannis”, which is Latin for “Thus always to tyrants”. Booth fled the stage through a door to the alley where a getaway horse was waiting and, at some point, injured his leg. Booth would later say that it was during his jump to the stage; however, others say he was injured when the horse tripped and fell on him during his escape. Regardless, Booth and David Herold made it to southern Maryland and en route to rural Virginia.

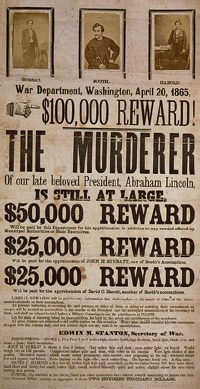

John Wilkes Booth Wanted Poster

After stopping at Surratt’s Tavern, where they had stored guns and equipment during their kidnapping plot, the fugitives continued on to the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, who treated Booth’s leg fracture in the early morning of April 15. That same morning, shortly after 7 a.m., President Lincoln died.

Booth and Herold went to Samuel Cox’s home and hid in the woods the next day. Cox then contacted his foster brother and Confederate agent, Thomas Jones. By this time, Federal troops were searching southern Maryland, and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton advertised a $100,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of Booth and his accomplices.

As Booth and Herold waited in the Maryland woods, some of the co-conspirators were captured, including Mary Surratt, mother of John Surratt, Lewis Powell, along with Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen, whom Booth had earlier recruited as underground operators for the Confederacy. John was aware of their arrests as he was brought newspapers every day by Jones. He was dismayed how even anti-Lincoln newspapers showed little sympathy for him.

On April 21, Booth and Herold decided it was time to cross the Potomac River into Virginia. After a failed attempt that landed them back in Maryland, they finally made it on April 23. Another Confederate agent provided them with horses, and the pair found refuge at Richard H. Garrett’s farm just south of Port Royal on April 24. The Garretts were told that Booth was James Boyd, a Confederate soldier who was returning home, and they were unaware of the President’s assassination.

Federal Soldiers tracked The pair there, and on the morning of April 26, they were found hiding in Garrett’s barn. Herold surrendered, but Booth refused. After the soldiers set the barn ablaze, Booth was moving about in the barn and was shot by Sergeant Boston Corbett, who says Booth had raised his pistol at him. Booth was fatally wounded in the neck and dragged from the barn to Garrett’s porch, where he died three hours later. His body was identified by a doctor who had operated on Booth the year before and was secretly buried, then re-interred four years later. Despite many theories that Booth actually escaped, there is no acceptable evidence to support the rumors.

Eight others were implicated in the assassination and were tried by a military tribunal in Washington, D.C., all of them being found guilty on June 30, 1865. Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, Mary Surratt, and David Herold were executed on July 7. Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold, and Michael O’Laughlen were sentenced to life in prison. While O’Laughlen died of yellow fever in 1867, the others were eventually pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in 1869.

©Dave Alexander /Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

The Largest K.G.C. Treasure Ever Found

Abraham Lincoln – Standing as a Hero

Assassination of President Abraham Lincoln

Civil War (main page)

Civil War Photo Print Galleries

Sources: