By John D. Billings in 1861

A false impression about the quantity and quality of the food furnished to the soldiers has been obtained. I have often been asked whether I always got enough to eat in the army and have surprised inquirers by answering in the affirmative. Some old soldier who sees this may reply, “Well, you were lucky. I didn’t.” But I should at once ask him to tell me for how long his regiment was ever without food of some kind. Of course, I am not now referring to our prisoners of war, who were starved by the thousands. And, I would be very much surprised if he should say more than 24 or 30 hours outside. I would grant that he might have been so situated as to be deprived of food a longer time, possibly when he was on an exposed picket post, serving as rear-guard to the army or doing something that temporarily separated him from his company. Still, his case would be the exception and not the rule.

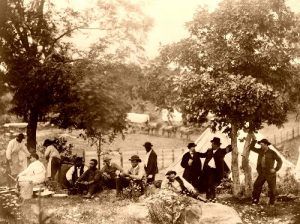

Sometimes, when active operations were in progress, the army was compelled to wait a few hours for its trains to come up, but no general hardship to the men ever ensued on this account. Such a contingency was usually known sometime in advance. The men would husband their last issue of rations or perhaps, if the country admitted, would make additions to their bill of fare in the shape of poultry or pork. Usually, it was the latter, for the Southerners did not pen up their swine as the Northerners but let them wander about, getting their living much of the time as best they could.

I will now give a complete list of the rations served to the rank and file as I remember them. They were salt pork, fresh beef, salt beef, rarely ham or bacon, hard bread, soft bread, potatoes, an occasional onion, flour, beans, split peas, rice, dried apples, dried peaches, desiccated vegetables, coffee, tea, sugar, molasses, vinegar, candles, soap, pepper, and salt.

It is scarcely necessary to state that these were not all served at one time. There was but one kind of meat served at once, usually pork. When it was hard bread, it wasn’t soft bread or flour; when it was peas or beans, it wasn’t rice.

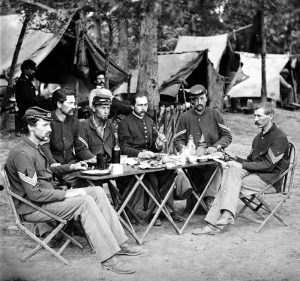

The commissioned officers fared better in camp than the enlisted men. Instead of drawing rations after the manner of the latter, they had a certain cash allowance, according to rank, with which to purchase supplies from the Brigade Commissary, an official whose province was to keep stores on sale for their convenience.

I will speak of the rations more in detail, beginning with the hard bread or using the name by which it was known in the Army of the Potomac, Hardtack. What was hardtack? It was a plain flour-and-water biscuit. Two that I possess as mementos measure three and one-eighth by two and seven-eighths inches and are nearly half an inch thick. Although these biscuits were furnished to organizations by weight, they were dealt out to the men by number, nine constituting a ration in some regiments and ten in others. Still, there were usually enough for those who wanted more, as some men would not draw them. While hardtack was nutritious, a hungry man could eat his ten quickly and still be hungry. When they were poor and fit objects for the soldiers’ wrath, it was due to one of three conditions: first, they may have been so hard that they could not be bitten; it then required a powerful blow of the fist to break them; the second condition was when they were moldy or wet, as sometimes happened, and should not have been given to the soldiers: the third condition was when from storage they had become infested with maggots.

When the bread was moldy or moist, it was thrown away and made good at the next drawing so that the men were not the losers. Still, in the case of its being infested with the weevils, they had to stand it as a rule, but hardtack was not so bad an article of food, even when traversed by insects, as may be supposed. Eaten in the dark, no one could tell the difference between it and untenanted hardtack. It was not uncommon for a man to find the surface of his pot of coffee swimming with weevils after breaking up hardtack in it, which had come out of the fragments only to drown, but they were easily skimmed off and left no distinctive flavor behind.

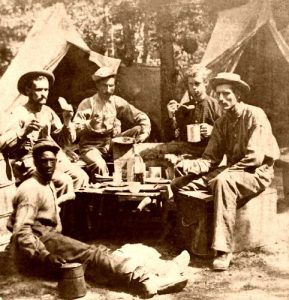

Having gone so far, I know the reader will be interested to learn of the styles in which the soldiers served up this particular article. Of course, many of them were eaten just as they were received — hardtack plain; then I have already spoken of their being crumbed in coffee, giving the “hardtack and coffee.”

Probably more were eaten this way than in any other, for they thus frequently furnished the soldier his breakfast and supper. But there were other and more appetizing ways of preparing them. Many of the soldiers, partly through a slight taste for the business but more from the force of circumstances, became, in their way and opinion, experts in the art of cooking the greatest variety of dishes with the smallest amount of capital.

Some of these crumbed them in soups for want of other thickening. For this purpose, they served very well. Some crumbed them in cold water, then fried the crumbs in the juice and fat of meat. A dish akin to this one, which was said to make the hair curl and certainly was indigestible enough to satisfy the cravings of the most ambitious dyspeptic, was prepared by soaking hardtack in cold water, then frying them brown in pork fat, salting to taste. Another name for this dish was Skillygalee. Some liked them toasted, either to crumbs in coffee or to butter if a sutler was at hand whom they could patronize. The toasting generally took place from the end of a split stick.

Then they worked into milk-toast made of condensed milk at 75 cents a can, but only a recruit with a big bounty, or an old vet, the child of wealthy parents, or a reenlisted man did much in that way. A few who succeeded by hook or by crook in saving up a portion of their sugar ration spread it upon hardtack. And so, in various ways, the ingenuity of the men was taxed to make this plainest and commonest, yet most serviceable of army food to do duty in every conceivable combination.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2020.

Notes and Author: This tale is adapted from a story written by a soldier named John D. Billings. The article is not verbatim from Billings’ original tale, as it has been edited for clarity. Note that it was written in 1861. As the Civil War continued, conditions for the troops on both sides of the line worsened as the war dragged on. It might have been interesting to know how Mr. Billings’ feelings might have changed had he written another account three years later. Hardtack and Coffee was a chapter included in Albert Bushnell Hart’s book, The Romance of the Civil War, published in 1896. However, the text as it appears here is not verbatim, as it has been edited.

Also See: