by Wilbur F. Gordy in 1903

Dr. Benjamin Franklin, a leading Founding Father of the United States, was also an author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat. He earned the title of “The First American” for his tireless campaigning for colonial unity.

Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 17, 1706, the 15th child in a family of 17 children. His father was a candle maker and soap boiler. Intending to make a clergyman of Benjamin, he sent him to a grammar school to fit him for college at the age of eight. The boy made rapid progress, but before the end of his first school year, his father took him out due to the expense and put him into a school where he would learn more practical subjects, such as writing and arithmetic. The last study proved very difficult for him.

Two years later, at the age of ten, he began to work in his father’s shop, where he spent his time cutting wicks for the candles, filling the molds with tallow, selling soap in the shop, and acting the part of errand boy.

He had often watched the vessels sailing in and out of Boston Harbor and often, in his imagination, had gone with them on their journeys. Now he longed to become a sailor and, quitting the drudgery of the candle shop, to roam out over the sea in search of a more interesting life. But his father wisely refused to let him go. However, his fondness for the sea took him frequently to the water, and he learned to swim like a fish and row and sailboats with great skill. In these sports, as in others, he became a leader among his playmates.

With all his dislike for the business of candle-making and soap-boiling and with all his fondness for play, he was still faithful in doing everything that his father’s business required. His industry, his liking for good books, and his keen desire for knowledge went far toward supplying the lack of school training. He spent most of his leisure time reading and devoted his savings to collecting a small library.

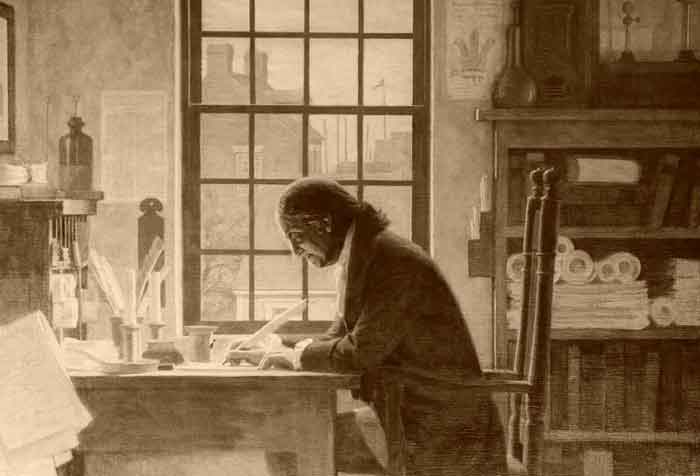

His father, noting his bookish habits, apprenticed Benjamin to his older brother, James, a printer in Boston. Benjamin was to serve until he was 21 and to receive no wages until the last year. In this position, he saw more books and used his opportunities well. Often, he would read, far into the night, a borrowed book that had to be returned in the morning. He also wrote some verses and peddled them about the streets until his father discouraged him by ridiculing his efforts.

About this time, to get money for books, he told his brother that he would be willing to board himself on half the money the board had been costing. To this, his brother agreed, and Benjamin lived on a very meager diet. Remaining in the printing office at noon, he ate a simple lunch as a biscuit or slice of bread and a bunch or two of raisins. As a meal like this required but little time, young Franklin could spend most of the noon hour reading. By living this way, he easily saved half of what his brother allowed him and at once spent his savings on books.

His youth was never idle because he put a high value on time; he was never wasteful of money because he knew the easiest way to make money was to save what he had. These were qualities that helped Benjamin Franklin to get on in the world. But, during this period, he had great hardships to bear, for his brother was a stern taskmaster and so hot-tempered that he would sometimes beat Benjamin cruelly. Ultimately, the two brothers had so many disagreements that Benjamin determined to run away and seek his fortune elsewhere. Having sold some of his books for a little money, he secured a passage on board a sloop for New York at 17. Upon his arrival, friendless and almost penniless, he began to visit the printing offices in search of work. But failing to find any and being told that he would be more likely to succeed in Philadelphia, he soon headed to Pennsylvania.

At that time, the journey, just a distance of 90 miles, was difficult. He first had to go by sailboat from New York to Amboy on the New Jersey coast. A storm came up on the way, tearing the sails and driving the boat to the Long Island shore. All night, Franklin lay in the hold while the waves dashed angrily over the boat. At length, after 30 hours, during which he was without food or water, he landed at Amboy. As he had no money to spare for coach hire, he started to walk along the rough country roads, the fifty miles across New Jersey to Burlington. For over two days, he trudged along in a downpour of rain. At the end of his first day’s journey, he was so wet and mud-spattered and had such an appearance of neglect that on reaching an inn, there was talk of arresting him for being a runaway servant.

Having arrived at Burlington, he was still 20 miles from Philadelphia and boarded a boat for the remainder of his journey. With no wind, the passengers had to take turns at the oars, so they continued down the Delaware River. The next day, they reached Philadelphia, and young Franklin, poorly clad and travel-soiled, with only a little money in his pocket, was making his way alone through the streets of Philadelphia. But he was cheerful and full of hope.

He found work quickly with one of the two master printers in Philadelphia. One day, while at work in the printing office, he received a call from Sir William Keith, Governor of Pennsylvania. Governor Keith’s attention had been directed to this 17-year-old youth by Franklin’s brother-in-law, and he called on this occasion to urge him to start a printing press of his own. When Franklin said he had no money to buy a printing press and type, the Governor offered to write a letter for Franklin to take to his father in Boston, asking him to furnish the loan. The following spring, Franklin took the letter to his father, who refused to lend him the money.

Upon Franklin’s return to Philadelphia, Governor Keith advised him to go to England to select the printing press and other things necessary for the business outfit, promising to provide funds. Franklin took him at his word and sailed for London, expecting to secure the money upon his arrival there. But, the faithless Governor failed to keep his word, and Franklin was again stranded in a strange city. Without friends and money, he once more found work in a printing office, where he remained during the two years of his stay in London.

After earning enough money, he finally returned to Philadelphia in 1726. Four years later, in 1730, 24-year-old Franklin publicly acknowledged an illegitimate son named William, who would eventually become the last Loyalist governor of New Jersey. That same year, he established a common-law marriage with Deborah Read on September 1, 1730. The couple took in Franklin’s young, recently acknowledged illegitimate son, William, and would later have two children of their own.

In the meantime, he had set up the printing business for himself but, in so doing, had to carry a heavy debt. He worked early and late to pay it off, sometimes making his own ink and casting his own type. He would also, at times, go with a wheelbarrow to bring the paper he needed to the printing office. His wife assisted him by selling stationery in his shop, and the family lived very simply.

On observing how hard Franklin worked, people said, “There is a man who will surely succeed. Let us help him.” During these early struggling years, Franklin was cheerful and light-hearted and diligently continued his reading habits, constantly trying to improve himself. He also adopted rules of conduct, some of which, in substance, were: Be temperate; speak honestly; be orderly about your work; do not waste anything; never be idle; when you decide to do anything, do it with a brave heart.

Some of the wisest things Franklin ever said appeared in his Almanac, which he called Poor Richard’s Almanac. Beginning when he was 26 years old, he published it yearly for 25 years, building up a very large circulation. It contained many homely maxims, which are as good today as they were in Franklin’s time. Here are a few of them:

- “God helps them that help themselves.”

- “Early to bed and early to rise, Makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.”

- “There are no gains without pains.”

- “One today is worth two tomorrows.”

- “Little strokes fell great oaks.”

- “Keep thy shop, and thy shop will keep thee.”

Benjamin Franklin always had a deep interest in public welfare. He started a subscription library in Philadelphia and established an academy, which finally grew into the University of Pennsylvania. Having a decidedly practical turn of mind, he had significant influence in organizing a better police force and a better fire department. He invented the Franklin stove, which became popular because it was much better than the open fireplace. But the most wonderful thing he ever did was prove that lightning was the same thing as electricity.

Before making this discovery, men of science had learned how to store electricity in a Leyden jar. But Franklin wished to discover something about the lightning that flashed across the clouds during a thunderstorm. Therefore, making a kite out of silk and fastening to it a small iron rod, he attached a string made of hemp to the kite and the iron rod.

One day, when a thundercloud was coming up, he went out with his little son and took his stand under a shelter in the open field. An iron key was fastened at one end of the hempen string, and to this was tied a silken string, which Franklin held in his hand. As electricity will not run through silk, he protected himself against the electric current by using this silken string.

Franklin watched intently when the kite rose high into the air to see what might follow. After a while, the fibers of the hempen string began to move, and then, putting his knuckles near the key, Franklin drew forth sparks of electricity. He was delighted, for he had proved that the lightning in the clouds was the same thing as the electricity that men of science could make with machines. It was a great discovery and made Benjamin Franklin famous. From some of the leading universities in Europe, he received the title of Doctor, and he was now recognized as one of the great men in the world.

Franklin rendered his country with numerous distinguished public services, so many they cannot all be mentioned here. More than 20 years before the outbreak of the American Revolution, he perceived that the principal source of weakness among the colonies was their lack of union. With this great weakness in mind, Franklin proposed, in 1754, at a time when the French were threatening to cut off the English from the Ohio Valley, his famous “Plan of Union.” Although it failed, it prepared the colonies for union in the struggle against King George and the English Parliament.

Ten years after proposing the “Plan of Union,” Franklin was sent to England to make a strenuous effort to prevent its passage during the agitation over the Stamp Act. He was unsuccessful in accomplishing his mission but later did much toward securing the repeal of the Stamp Act.

Returning from England two weeks after the Battle of Lexington and Concord, he immediately took a prominent part in the Revolution. He was one of the five appointed to a committee to write the Declaration of Independence. During their discussion, he allegedly said, ” Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

After signing the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, he was sent to France to secure aid for the American cause. The French people gave him a cordial reception. There were feasts and parades in his honor, crowds followed him on the streets, and his pictures were displayed everywhere. The simplicity and directness of this white-haired man of 70 years charmed the French people and won him a warm place in their hearts. On one of the great occasions, a very beautiful woman was appointed to place a crown of laurel upon his white locks and to give the old man two kisses on his cheeks. All this was a sincere expression of admiration and esteem. He did very much to secure from France the aid that that country gave us. He indeed rendered services to his country, whose value may be compared with those of George Washington.

Franklin left France in 1785 after having represented his country ably for ten years. All of France was sorry to have him leave. Since it was hard for him to endure the motion of a carriage, the King sent one of the Queen’s litters, in which he was carried to the coast. He also bore with him a portrait of the King of France “framed in a double circle of four hundred and eight diamonds.”

Although he had to endure much idleness and pain in his last years, he was uniformly patient and cheerful, loving life to the end. He died on April 17, 1790, at the age of 84, one of the greatest American statesmen and heroes.

As a scientist, he was a significant figure in the American Enlightenment and the history of physics for his discoveries and theories regarding electricity. He invented the lightning rod, bifocals, the Franklin stove, a carriage odometer, and the glass armonica. He formed the first public lending library in America and the first fire department in Pennsylvania. Though he was world-famous as a scientist and a diplomat at the time of his death, he named himself in his will simply “Benjamin Franklin, Printer.”

By Wilbur F. Gordy, 1903. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

About the Article: This article was, for the most part, written by Wilbur F. Gordy and included in a chapter of his book American Leaders and Heroes, published in 1903 by Charles Scribner and Sons, New York. However, the original content has been heavily edited, and additional information has been added.

Also See: