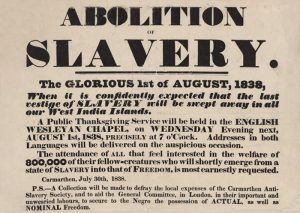

Abolitionists were people who believed that slavery was immoral and wanted to end slavery in the United States. They influenced political debates in the United States from the late 17th century through the Civil War.

The first attempts to end slavery in the British/American colonies came from Thomas Jefferson and some of his contemporaries. Even though Jefferson was a lifelong slaveholder, he included strong anti-slavery language in the original draft of the Declaration of Independence. Still, other delegates took it out before it was finalized. Benjamin Franklin, also a slaveholder for much of his life, became a leading member of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, the first recognized abolitionist organization in the United States. Following the American Revolution, several Northern states abolished slavery, beginning with Vermont in 1777 and Pennsylvania in 1780. Other states with more of an economic interest in slaves, such as New York and New Jersey, also passed gradual emancipation laws, and by 1804, all the northern states had abolished it.

In 1831 William Lloyd Garrison began the publication of the Liberator, the first newspaper in the United States to take a radical stand for the abolition of slavery. Two years later, the National Anti-Slavery Society was organized in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In a short time, the organization members became divided to some extent as to the methods to be pursued in the efforts to secure the emancipation of the slaves. Some clung to the theory of gradual freeing of the slaves, compensating the slaveholders as a last resort. In contrast, others advocated the immediate and unconditional liberation of every slave, by force if necessary, and without compensating their owners. These extremists in 1835 were nicknamed “abolitionists” by those who favored slavery and also by the conservative element in the society. Although this name was first applied in a spirit of derision, the extremists accepted it as an honor. In a short time, several abolitionist orators, speakers of more than ordinary ability, came forward. Among these men were Wendell Phillips, Gerrit Smith, and Charles Sumner, who never lost an opportunity of presenting their views.

The society became divided in 1840 on the question of organizing a political party on anti-slavery lines. From that time, each branch worked in its own way. By the time Kansas was organized as a territory, the abolitionists — the radical wing of the original society — had become strong enough to attract attention from one end of the country to the other.

The society became divided in 1840 on the question of organizing a political party on anti-slavery lines. From that time, each branch worked in its own way. By the time Kansas was organized as a territory, the abolitionists — the radical wing of the original society — had become strong enough to attract attention from one end of the country to the other.

The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which organized these two territories for settlement, also allowed the residents of each state to vote on whether or not to allow slavery when the territory became a state. This approach was called popular sovereignty.

Among the pro-slavery men, there was no distinction between those who favored the gradual, peaceable emancipation of the slave and those who were in favor of immediate emancipation at whatever cost. Many pro-slavery advocates regarded the Free-State men as “abolitionists” indiscriminately.

At a pro-slavery squatter meeting near Leavenworth, Kansas, on June 10, 1854, a resolution was adopted declaring that “We will afford protection to no abolitionist as a settler in Kansas.” A pro-slavery meeting in Lafayette County, Missouri, on December 15, 1854, denounced the steamboats plying on the Missouri River for carrying abolitionists to Kansas. As a result of this agitation, the Star of the West in the spring of 1856 was allowed to carry about 100 persons from Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina to Kansas unmolested. Still, on her next trip, with several Free-State passengers, she was held up at Lexington, Missouri, where the passengers were disarmed, and upon arriving at Weston, Missouri, was not permitted to land. Other steamers encountered similar opposition.

In February 1855, Lawrence, Kansas, was denounced because it was “the home of about 400 abolitionists.” At a Law and Order meeting at Leavenworth on November 15, 1855, John Calhoun said: “You yield, and you will have the most infernal government that ever cursed a land. I would rather be a painted slave over in Missouri, or a serf to the Czar of Russia, than have the abolitionists in power.”

On October 5, 1857, occurred the election for members of the Territorial Legislature. On October 23rd, the Doniphan Constitutionalist, a pro-slavery newspaper, accounted for the Free-State victory by saying that the “sneaking abolitionists were guilty of cutting loose the ferry boats at Doniphan and other places on the day of the election, by order of James H. Lane.” To this, the Lawrence Republican retorted: “Badman, that Jim Lane, to order the boats cut loose; great inconvenience to the Missourians and the Democratic Party.”

At the beginning of the border troubles, the Platte Argus said editorially: “The abolitionists will probably not be interfered with if they settle north of the 40th parallel of north latitude, but south of that line they need not set foot.”

A pro-slavery convention at Lecompton, Kansas, on December 9, 1857, adopted resolutions denunciatory of Governors Reeder, Geary, and Walker for their efforts “to reduce and prostitute the Democracy to the unholy ends of the abolitionists.”

These instances might be multiplied indefinitely, but enough has been said to show that the pro-slavery men made no distinction whatever between the radical and conservative wings of the Free-State party. If a man was opposed to slavery, though willing to let it alone where it already existed, he was just as much of an “abolitionist” as the extremist who would be satisfied with nothing less than the immediate emancipation of all slaves, without regard to constitutional guarantees or the simplest principles of equity.

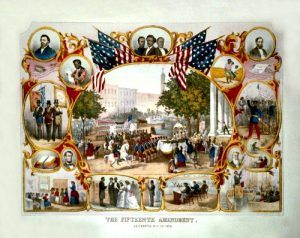

The radical anti-slavery people claimed that the Civil War was an anti-slavery conflict and maintained that this view was justified by the emancipation proclamation of President Abraham Lincoln, notwithstanding Lincoln’s previous utterance that he was not striving to abolish slavery but to preserve the Union.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2021.

Also See:

Kansas-Missouri Border War Timeline

Pro-Slavery Movement in Kansas

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.

Kansapedia

Wikipedia