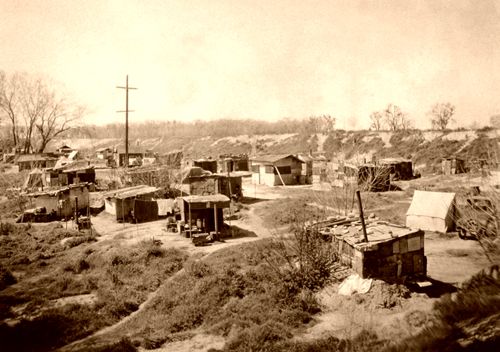

Hooverville: A crudely built camp put up usually on the edge of a town to house the many poverty-stricken people who had lost their homes during the Depression of the 1930s.

~~

Many shanty towns that sprung up all over the nation during the Great Depression were facetiously called Hoovervilles because so many people at the time blamed President Herbert Hoover for letting the nation slide into the Great Depression. Coined by Charles Michelson, the Publicity Chief of the Democratic National Committee, it was first used in print media in 1930 when The New York Times published an article about a shantytown in Chicago, Illinois. The term caught on quickly and was soon used throughout the country.

Though homelessness has been a problem throughout the ages and was a common sight in the 1920s, as hobos and tramps lounged in city streets and rode the rails, it has never been more present in the United States than it was during the Great Depression.

The causes of the Great Depression varied, beginning with rapid economic growth and financial excess of the “Roaring Twenties.” During this time, many Americans quickly bought automobiles and appliances and speculated in the stock market. Unfortunately, much of this wild spending was done on credit, and while businesses were making huge gains, the average workers’ wages were not increasing at anywhere near the same rate.

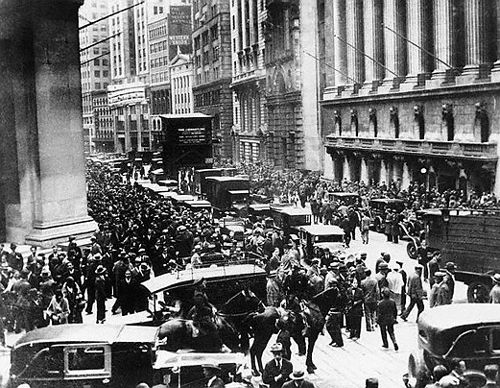

But, like other “booms” throughout history, the cycle soon led to a “bust.” As manufacturing output continued and farmers were overproducing, circumstances changed, leading to falling prices and rising debt. At the same time, there was a major banking crisis and serious policy mistakes by the Federal Reserve Board. With the stock market crash in October 1929, the country was thrown into a full-blown depression that would affect the nation for nearly a decade.

Businesses began to lay off people, quickly followed by homelessness as the economy crumbled in the early 1930s. Homeowners lost their property when they could not pay mortgages or pay taxes. Renters fell behind and faced eviction. Many squeezed in with relatives, but hundreds of thousands were less fortunate. Some defied eviction, staying where they were. Others found refuge in one of the increasing numbers of vacant buildings, and more found shelter under bridges, culverts, empty water mains, or on vacant public lands, where they built crude shacks. When the Dust Bowl began in 1931, it made matters even worse. By 1932, millions of Americans were living outside the “normal” housing market. Between 1929 and 1933, more than 100,000 businesses failed nationwide, and when President Hoover left office in 1933, the national unemployment rate was nearly 25%.

As these many people used whatever means they had at their disposal for survival, they blamed Hoover for the downfall of economic stability and lack of government help. Making matters worse, the minimal federal help that was provided often didn’t go to the sick, hungry, and homeless, as many state and local politicians of the time were corrupt.

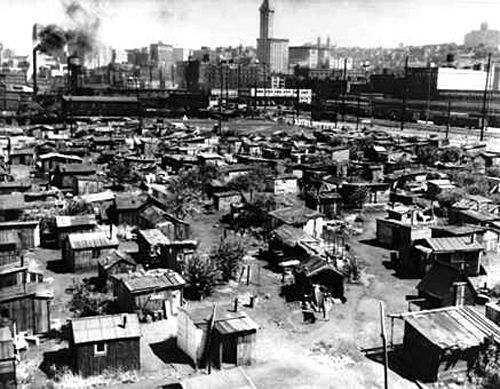

These teeming communities of makeshift shacks, known as “Hoovervilles,” were often concentrated in cities close to soup kitchens run by charities. The shelters varied widely, from stone houses and fairly solid structures built by those with construction skills to many thrown together with wooden crates, cardboard, tar paper, scraps of cloth and metal, and various other discarded materials. Within their shelters, most people had a small stove, a few cooking implements, some bedding, and little else.

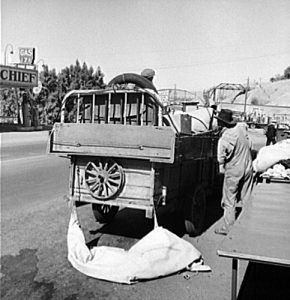

More derogatory terms blaming Hoover were also coined, including a “Hoover blanket,” which was an old newspaper used for blanketing; “Hoover leather,” was cardboard used to line a shoe when the sole had worn through; a “Hoover wagon” was an automobile with horses tied to it because the owner could not afford fuel; freight cars used for shelter were called “Hoover Pullmans,” and a “Hoover flag” was an empty pocket turned inside out.

These settlements were often established on empty land and were rarely “recognized” by authorities as they were tolerated or ignored out of necessity. However, that was not always the case, especially if the occupants were trespassing on private lands and some cities would not allow them.

In May 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” enacted a special relief program called the Federal Transient Service (FTS). Shelters were established by the program that provided food, clothing, medical care, and training and education programs. The relief also provided for rooms in boarding houses and rent payments. A few camps were established in rural areas, but in the cities, the Federal Government saw the problem as a local one.

The program helped many, but it could not help thousands of others, and just two years later, in 1935, it was phased out. The plan was to get the homeless into work-related programs, such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA). However, only about 20% of those formerly housed by the FTS could get jobs in the work programs. Though some were eligible for the Resettlement Administration camps established for migratory workers, they were still insufficient.

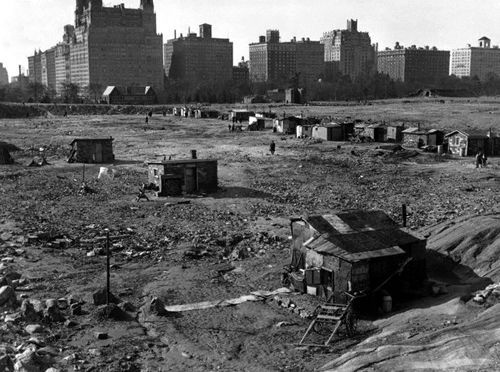

Upper West Side, Manhattan, New York — Hooverville in Central Park 1933 — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

One such Hooverville “town” was located in New York City’s Central Park. When the stock market crashed in 1929, it occurred just as a rectangular reservoir north of Belvedere Castle was being taken out of service. By 1930, a few homeless people set up an informal camp at the drained reservoir but were soon evicted. But, having nowhere to go, they would return, and as public sentiment became more sympathetic, they were allowed to stay. Called “Hoover Valley,” the reservoir soon sported several shacks on what was labeled “Depression Street.” One was even built of brick with a roof of inlaid tile constructed by unemployed bricklayers. Others built a dwelling from stone blocks of the reservoir, including one shanty that was 20 feet tall. Though the settlement could not have been popular with the tenants of the new Fifth Avenue and Central Park West apartments, they mounted no protest.

There were other such settlements in New York – one called “Hardlucksville,” which boasted some 80 shacks between Ninth and 10th Streets on the East River. Another called “Camp Thomas Paine” existed along the Hudson in Riverside Park. Central Park disappeared sometime before April 1933 when work on the reservoir landfill resumed.

In Seattle, Washington, stood one of the country’s largest, longest-lasting, and best-documented Hoovervilles, standing for ten years between 1931 and 1941. Though several were located about the city, Hooverville was on the tidal flats adjacent to the Port of Seattle. The camp began when an unemployed lumberjack Spread over nine acres; it housed a population of up to 1,200. The camp began when an unemployed lumberjack named Jesse Jackson and 20 other men started building shacks on the land. Within a few days, 50 shanties were made available to the homeless. However, the Health Department soon posted notices on every shack to vacate them within a week. When the residents refused, the shacks were burned down. But, they were immediately rebuilt, burned, and rebuilt again, this time underground, with a roof made of tin or steel. With Jesse Jackson acting as a liaison between Hooverville residents and City Hall, the Health Department finally relented and allowed them to stay on the condition that they adhere to safety and sanitary rules. Jackson became the de facto mayor of the shantytown, including its form of community government. Before World War II, the “town” existed until the land was needed for shipping facilities.

Chicago, Illinois Hooverville sprung up at the foot of Randolph Street near Grant Park, which also claimed its form of government, with a man named Mike Donovan, a disabled former railroad brakeman and miner, as its “Mayor.” In an interview with a reporter, Donovan would say, “Building construction may be at a standstill elsewhere, but down here, everything is booming. Ours is a sort of communistic government. We pool our interests, and when the commissary shows signs of depletion, we appoint a committee to see what leavings the hotels have.”

Another large Hooverville was situated along the banks of the Mississippi River in St. Louis, Missouri. Supporting some 500 people, it consisted of four distinct racial sectors, though the people integrated to “support” their city. They also had an unofficial mayor named Gus Smith, who was also a pastor. The community, which depended primarily on private donations and scavenging, created its churches and other social institutions. It remained a viable community until 1936, when the federal Works Progress Administration allocated slum clearance funds for the area.

These are a few examples: Hoovervilles existed all over the United States — at the edges of Portland, Oregon, Washington D.C., Los Angeles, California, and everywhere in between.

In the latter half of the 1930s, the homeless increased as factories closed and farmers were displaced. The problem was made worse as more and more states increased residency requirements for the homeless to apply for relief, requiring them to have lived there a certain amount of time and other conditions. For the many transients, this made them ineligible.

The private shelters were overwhelmed, and city officials were trying to “police” the many vagrants, which led to increased hostility towards the homeless. Some communities, especially in the South and West, used extralegal means, such as border patrols, indigent laws, forced removals, and unwarranted arrests, to keep the homeless out.

California was the “hardest hit” by transients during the Depression years. Having only 4.7% of the population when it began, they would wind up with 14% of the nation’s transients. Overwhelmed officials tried to figure out how to absorb as many as 6,000 migrants crossing its borders daily. Also, feeling the effects of the Depression, California infrastructures were already overburdened, and the steady stream of newly arriving migrants was more than the system could bear.

Los Angeles’s answer was the “Bum Blockade.” In February 1936, Los Angeles Police Chief James E. “Two-Gun” Davis, with the support of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, many public officials, the railroads, and hard-pressed state relief agencies, dispatched 136 police officers to 16 major points of entry on the Arizona, Nevada, and Oregon borders, with orders to turn back migrants with “no visible means of support.” This continued for several months until it was finally withdrawn when the use of city funds for this project was questioned, and several lawsuits were threatened.

When John Steinbeck’s book, The Grapes of Wrath, was published in 1939, it raised public sympathy for the homeless. However, his book focused on the drought refugees moving westward rather than most of the homeless population living in cities. In the end, though, it would encourage assistance. Just a month after the movie version was released in 1940, a Congressional House committee began hearings on interstate migration of the destitute. But, it would be World War II that would end the “problem.” As the nation turned its focus to defense, many homeless joined the military or found employment in war industries. Shelters closed, and relief programs were reduced. In the meantime, the American Civil Liberties Union, fighting states’ rights to restrict interstate migration, took their case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1941, agreeing that states could not restrict access by poor people or any other Americans. But, it would be almost three more decades, in 1969, before the Supreme Court declared the residency requirements for benefit eligibility unconstitutional.

Getting rid of these many Hoovervilles was difficult as their residents had nowhere to call home. Though numerous attempts were made to eliminate these villages during the 1930s, they were unsuccessful. The New Deal programs helped to eliminate many of the shantytowns. Still, some cities were not enthusiastic about federal initiatives, arguing that public housing would depress property values and make their cities susceptible to Communist influence.

Finally, in 1941, a shack elimination program was implemented, and the many Hoovervilles across the country were systematically eliminated. By this time, employment levels had risen, gradually providing shelter and security for formerly homeless Americans.

Homelessness would not recapture national attention until the late 1970s when it was thrust to the forefront due to deindustrialization and urban renewal.

The term “Hooverville” is still used to portray modern tent cities. However, the terms “Bushville” and “Obamaville” became more common when describing the encampments of the homeless and unemployed that appeared in the wake of mortgage foreclosures and the financial crisis of 2007–2010. Ironically, the current era of financial strife, preceded by decades of excess, includes many of those very same factors as the Great Depression, such as a major banking crisis, policy mistakes of the Federal Reserve Board, and excessive debt.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See:

The Bum Blockade – Stopping the Invasion of Depression Refugees