Dorothea Lange, a documentary photographer, and photojournalist, is best known for her Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Lange’s photographs humanized the consequences of the Great Depression and influenced the development of documentary photography.

Born on May 26, 1895, in Hoboken, New Jersey, she was initially named Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn at birth. Her early life was not easy, as she contracted polio at the age of seven, which left her with a weakened right leg and a permanent limp. Another traumatic event occurred when she was 12, and her father abandoned the family. After this, she dropped her middle name and assumed her mother’s maiden name.

Lange studied photography in New York City and, in 1918, decided to travel the world with a friend. However, that was cut short in San Francisco, California, when she was robbed, forcing her to stay where she earned her living as a portrait photographer for more than a decade.

In 1920, Lange married Maynard Dixon, a well-known western artist, and with Dixon, she had two boys, Daniel in 1925 and John in 1930.

During the Depression’s early years, Lange’s interest in social issues grew, and she began photographing the economy’s effects on city residents.

A 1934 exhibition of these photographs introduced her to Paul Taylor, an associate professor of economics at the University of California at Berkeley. In February 1935, the couple documented migrant farmworkers in Nipomo and the Imperial Valley for the California State Emergency Relief Administration. Copies of the reports Lange and Taylor produced reached Roy Stryker, who headed the Resettlement Administration and offered Lange a job in August 1935. Unlike the agency’s other photographers, Lange did not move to Washington but used her Berkeley home as a base of operations. Lange divorced Dixon and married Paul Taylor that winter.

Lange returned to the Imperial Valley in early 1937 for the Resettlement Administration. The valley was in a state of crisis, and on February 16, 1937, Lange reported on the situation to Stryker:

“I was forced to switch from Nipomo to the Imperial Valley because of the conditions there. They have always been notoriously bad, as you know, and what goes on in the Imperial is beyond belief. The Imperial Valley has a social structure all its own, and partly because of its isolation in the state, those in control get away with it. But, this year’s freeze practically wiped out the crop, and what it didn’t kill is delayed – in the meanwhile, because of the warm, no-rain climate and possibilities for work, the region is swamped with homeless moving families. The relief association offices are open day and night, 24 hours. The people continue to pour in, and there is no way to stop them and no work when they get there.”

As many as 6,000 migrants arrived in California from the Midwest every month, driven by unemployment, drought, and the loss of farms… In An American Exodus, which Paul Taylor co-authored with Lange, he wrote that the Okies and Arkies had “been scattered like the shavings from a clean-cutting plane.” Many drifted to the Imperial Valley after completing the Boulder (Hoover) Dam in 1936, which guaranteed the valley water supply for irrigation. This put further pressure on the migrants, who were already competing with Mexicans and other immigrants for work.

In October 1936, due to shortages, funds forced Stryker to lay off the photographers; however, after just two months, he was able to rehire Lange in late January 1937. The several hundred photographs she took that year document the terrible conditions in California at the time, including makeshift camps on the banks of irrigation ditches, use of irrigation water for cooking and washing, crowds at the relief offices, and, when work was available, the stooped labor of working in the fields.

Lange’s photographs were intended to bolster support for establishing migrant camps in the area by the Resettlement Administration. On March 12, 1937, Lange wrote Stryker that her “negatives are loaded with ammunition.” She added that the situation was “no longer a publicity campaign for migratory agricultural labor camps” but rather “a major migration of people and a rotten mess.” To get the “word” out, the photographs were provided to state emergency relief offices, the U.S. Senate, for a Works Progress Administration (WPA) exhibit in San Francisco, and by several newspapers and periodicals, including Life magazine.

In 1941, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for excellence in photography. However, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, she gave up the prestigious award to record the forced evacuation of Japanese Americans to relocation camps on assignment for the War Relocation Authority (WRA). She photographed the rounding up of Japanese Americans and their internment in relocation camps. Her images were so critical that the Army impounded them at the time.

In 1945, Lange was invited by Ansel Adams to accept a position at the first fine art photography department at the California School of Fine Arts, which she accepted. Seven years later, in 1952, she co-founded the photographic magazine Aperture.

She suffered from poor health in the last two decades, including gastric problems, bleeding ulcers, and post-polio syndrome. Dorothea Lange died of esophageal cancer on October 11, 1965, at the age of 70.

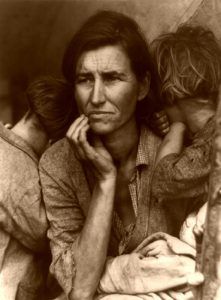

Migrant Mother, 1936 by Dorthea Lange.

She left behind thousands of photographs held by several California museums, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Library of Congress.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

Also See:

Dust Bowl Days or the “Dirty Thirties”

Farm Security Administration – A New Deal

Photographers Documenting History

0