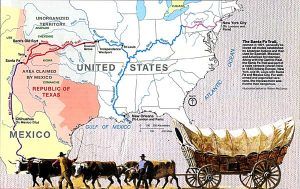

Between 1821 and 1880, the Santa Fe Trail was primarily a commercial highway connecting Missouri and Santa Fe, New Mexico. From 1821 until 1846, it was an international commercial highway used by Mexican and American traders. In 1846, the Mexican-American War began. The Army of the West followed the Santa Fe Trail to invade New Mexico. When the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war in 1848, the Santa Fe Trail became a national road connecting the United States to the new southwest territories. Commercial freighting along the trail continued, including considerable military freight hauling to supply the southwestern forts. Stagecoach lines also used the trail, thousands of gold seekers heading to the California and Colorado gold fields, adventurers, fur trappers, and emigrants. In 1880 the railroad reached Santa Fe, and the trail faded into history.

The Great Prairie Highway

The Santa Fe Trail stirs imaginations as few other historic trails can. For 60 years, the trail was one thread in a web of international trade routes. It influenced economies as far away as New York and London. Spanning 900 miles of the Great Plains between the United States (Missouri) and Mexico (Santa Fe), it brought together a cultural mosaic of individuals who cooperated and sometimes clashed. In the process, the rich and varied cultures of Plains Indians were caught in the middle and changed forever.

Spain jealously protected the borders of its New Mexico colony, prohibiting manufacturing and international trade. Missourians and others visiting Santa Fe told of an isolated provincial capital starved for manufactured goods and supplies, a potential gateway to Mexico’s interior markets.

In 1821, the Mexican people revolted against Spanish rule. With independence, they unlocked the gates of trade, using the Santa Fe Trail as the key. Encouraged by Mexican officials, the Santa Fe trade boomed, strengthening and linking the economies of Missouri and Mexico’s northern provinces.

Soldiers used the trail during the 1840s disputes between the Republic of Texas and Mexico, the 1846-48 Mexican-American War, and the Civil War, and troops policed conflicts between traders and Indian tribes. With the traders and military freighters tramped a curious company of gold-seekers, emigrants, adventurers, mountain men, hunters, American Indians, guides, packers, translators, reporters, and more.

The close of the Civil War in 1865 released America’s industrial energies, and the railroad pushed westward, gradually shortening and then replacing the Santa Fe Trail.

Life on the Trail

Movies and books often romanticize Santa Fe Trail treks as sagas of constant peril, replete with violent prairie storms, fights with Indians, and thundering buffalo herds. A glimpse of bison, elk, pronghorn antelope, or prairie dogs was sometimes the only break in the monotony of eight-week journeys. Trail travelers mainly experienced dust, mud, gnats and mosquitoes, and heat. But, occasional swollen streams, wildfires, hailstorms, strong winds, or blizzards could imperil wagon trains.

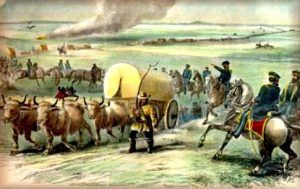

At dawn, trail hands scrambled in noise and confusion to round up, sort, and hitch up the animals. The wagons headed out, the air ringing with whoops and cries of “All’s set!” and soon, “Catch up! Catch up!” and “Stretch out!” Stopping at mid-morning, crews unhitched and grazed the teams, hauled water, gathered wood or buffalo chips for fuel, and cooked and ate the day’s main meal from a monotonous daily ration of one pound of flour, one pound or so of bacon, one ounce of coffee, two ounces of sugar, and a pinch of salt. Beans, dried apples, or bison, or other game were occasional treats. Crews then repaired their wagons, yokes, harnesses, greased wagon wheels, doctored animals, and hunted.

They moved on soon after noon, fording streams before the night’s stop because overnight storms could turn trickling creeks into torrents. Livestock that was cold in the harness first thing in the morning tended to be unruly. At day’s end, crews took care of the animals, made necessary repairs, chose night guards, and enjoyed a few hours of well-earned leisure and sleep.

“The Vast Plains, Like A Green Ocean”

Freight Team on the Plains

Westward from Missouri, forests – and then tallgrass prairie – give way to the prairie in Kansas. In western Kansas, roughly at the 100th Meridian, semi-arid conditions develop. For trail travelers, venturing into the unknown void of the plains could hold the fear of hardship or the promise of adventure. Long days traveling through seemingly endless expanses of tall and short grass prairie, with a few narrow ribbons of trees along waterways, evoked vivid descriptions. “In spring, the vast plain heaves and rolls around like a green ocean,” wrote one early traveler. Another marveled at a mirage in which “horses and the riders upon them presented a remarkable picture, apparently extending into the air… 45 to 60 feet high… At the same time, I could see beautiful clear lakes of water with… bulrushes and other vegetation…” Other trail travels dreamed of cures for sickness from the “purity of the plains.”

Deceptively empty of human presence as the prairie landscape might appear, the lands the trail passed through were the long-held homelands of many American Indian people. Here were the hunting grounds of the Comanche, the Kiowa, southern bands of the Cheyenne and the Arapaho, and the Plains Apache, as well as the homelands of the Osage, the Kanza (Kaw), the Jicarilla Apache, the Ute, and the Pueblo Indians. Most early encounters were peaceful negotiations centering on access to tribal lands and trade in horses, mules, and other items that Indians, Mexicans, and Americans coveted.

As trail traffic increased, so did confrontations – resulting from misunderstandings and conflicting values that disrupted traditional lifeways of American Indians and trail traffic. Mexican and American troops provided escorts for wagon trains. Growing numbers of trail travelers and settlers moved west, bringing the railroad with them. As lands were parceled out and the bison were hunted nearly to extinction, Indian people were pushed aside or assigned to reservations.

Soldiers and Forts

Suspicion and tension between the United States and Mexico accelerated in the 1840s. With the American need for territorial expansion, Texans raided into New Mexico, and the United States annexed Texas. The Mexican-American War erupted in 1846. General Stephen Watts Kearny led his Army of the West down the Santa Fe Trail to take and hold New Mexico and upper California and protect American traders. He marched unchallenged into Santa Fe and, although communities such as Taos and Mora rebelled, American control prevailed. In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war.

The Santa Fe Trail became the lifeline for protection and communication between Missouri and Santa Fe. From a succession of military forts such as Forts Mann (1847), Atkinson (1850), and Larned (1859) in Kansas, Fort Union (1851) in New Mexico, and Fort Lyon (1860) in Colorado, the army controlled conflicts between American Indians and trail travelers. As the military presence grew, freighting and merchant operations burgeoned. In 1858, many of the 1,800 wagons traveling the Santa Fe Trail carried military supplies.

In 1862, the Civil War arrived in the West. Confederates from Texas pushed up the Rio Grande Valley into New Mexico, intent on seizing the territory and Fort Union, and ultimately the rich Colorado goldfields. Albuquerque and Santa Fe fell. But the tide turned at Glorieta Pass, New Mexico, on the Santa Fe Trail. In the most decisive western battle of the Civil War, Union forces secured victory when they torched the nearby Confederate supply train. The Confederates abandoned hope of reaching Fort Union – and keeping their foothold in New Mexico. The Union Army held the Southwest and its vital Santa Fe Trail supply line.

Commerce of the Prairies

The story of the Santa Fe Trail is a story of business – international, national, and local. In 1821, William Becknell, bankrupt and facing jail for debts, packed goods to Santa Fe and made a profit. Entrepreneurs and experienced business people followed – James Webb, Antonio Jose Chavez, Charles Beaubien, David Waldo, and others.

The Santa Fe Trade developed into a complex web of international business, social ties, tariffs, and laws. Merchants in Missouri and New Mexico extended connections to New York, London, and Paris. Traders exploited social and legal systems to facilitate business. Partnerships such as Goldstein, Bean, Peacock, and Armijo formed and dissolved. Dave Waldo converted to Catholicism and also became a Mexican citizen. Dr. Eugene Leitensdorfer of Missouri married Soledad Abreu, daughter of a former New Mexico governor. Trader Manual Alvarez claimed citizenship in Spain, the United States, and Mexico.

After the Mexican-American War, trail trade and military freighting boomed. Both firms and individuals – such as Russell, Majors, and Waddell, Otero and Sellar, and Vincente Romero – obtained and subcontracted lucrative government contracts. Others operated mail and stagecoach services.

Trade created other opportunities. From New York, Manuel Harmony shipped English goods to Independence for freighting over the Santa Fe Trail. New Mexican saloon owner Dona Gertrudis “La Tules” Barcelo invested in the trade, and trader Charles Ilfeld ran mercantile stores. Wyandotte Chief William Walter leased a warehouse in Independence, and his tribe invested in the trade. Hiram Young bought his freedom from slavery and became a wealthy maker of trade wagons and one of the largest employers in Independence. Blacksmiths, hotel owners, arrieros (muleteers), lawyers, and others found their places along the trail. Trade flourished. In 1822, trade totaled $15,000; by 1860, $3.5 million, or more than $53 million in today’s dollars.

The route played a significant role in bringing people, goods, and ideas to and from Santa Fe for almost 60 years. However, the Santa Fe Trail was rarely a static entity because the route across the plains and the trail’s eastern terminus were constantly in flux. This was especially true during the last 15 years of the trail’s history when the westward push of the railroads incrementally shortened the distance between Santa Fe and the most recently-built, end-of-track, “hell on wheels” railroad town.

Santa Fe Trail Timeline

1821

In 1821, Mexico gained its independence from Spain. Shortly after that, freighter and trader William Becknell blazed the Santa Fe Trail. Along with four trusted companions and mules packed with $300 worth of trade goods, he left Franklin, Missouri, on September 1, 1821. His route led him past the western boundary of Missouri and into the unorganized Indian Territory, which became the State of Kansas 40 years later.

His mule train passed through Morris County at what became known as Council Grove and then traveled across the open prairies to the Great Bend of the Arkansas River. They followed the river into Colorado, where they crossed it in the vicinity of present-day LaJunta. They then entered into a foreign land owned by Mexico. Following a well-worn trail, the men and mules struggled over the heights of Raton Pass and later came across a group of soldiers who escorted them into Santa Fe. This route over the Raton Mountains in present-day New Mexico was the forerunner for what became known as the Mountain Route. They had traveled 934 miles.

Arriving in mid-November, Becknell’s party spent the next month trading. On December 13, they left Santa Fe with their saddlebags overflowing with silver, having converted their three hundred dollars in goods to approximately six thousand dollars in coin.

The whole distance from the settlements on the Missouri to the mountains in the neighborhood of Santa Fe is a prairie country, with no obstructions to the route… A good wagon road can… be traced out, upon which a sufficient supply of fuel and water can be procured, at all seasons, except in winter.”

— Alphonso Wetmore, 1824

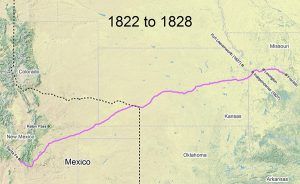

1822 – 1828

When William Becknell and his men returned home, he avoided the Raton Mountains and took a shorter, more direct route, which soon became known as the Cimarron Route. Most of those who made the trek in later years followed in Becknell’s footsteps. A few westbound parties started from Lexington, Missouri, but most departed from Franklin, Missouri. Independence, Missouri, founded in March 1827, also played a role as a trail town during this period. After returning along the Cimarron Route, having traveled some 890 miles, Becknell and his men arrived back in Franklin on January 22, 1822.

Almost immediately, Becknell began planning his next second journey to Santa Fe. This time, he chose to haul trade goods by wagon instead of pack mules and altered his original route to accommodate them slightly. The wagon train, which included three wagons of merchandise and 21 men, left Franklin, Missouri, in May 1822, making the trip on the Cimarron Route. The party proceeded to a point probably in present Rice County, Kansas, where they forded the Arkansas River. Beyond there, the party struck a southwest course for the Mexican Country. Before long, their journey brought them to a semi-arid region known by the Mexicans as Jornada Del Muerto, the journey of death.

After considerable hardship, including nearly dying of thirst, he and his men arrived in Santa Fe 48 days after their departure. The second trip proved to be even more profitable than the first. Taking an estimated $3,000 in goods to Santa Fe, Becknell’s party returned with a profit of around $91,000. Becknell would make a third profitable trip to Santa Fe in 1824.

However, word of the profits spread fast, and by the time Becknell made his second journey, he already had competition from other Santa Fe Traders. Colonel Benjamin Cooper with 15 men left Missouri for New Mexico two weeks before Becknell, and another party headed by John Heath caught up with and joined Becknell en route. Within the next two years, trade from Missouri along the Santa Fe Trail was in full swing. In 1824 a party of 80 men with 25 wagons, guided by Alexander Le Grand, carried $35,000 worth of goods and successfully sold them in New Mexico. His caravan returned from Santa Fe with $180,000 in gold and silver and $10,000 in furs, as well as mules.

Following Becknell’s initial trips, New Mexican officials encouraged American merchants to trade with Mexico. In 1824, Chihuahua and New Mexican merchants traveled from Santa Fe to Missouri, and Mexican merchants were sent to Washington D.C. to negotiate commercial agreements.

Within no time, a steady stream of American and European manufactured goods were on their way to New Mexico. However, the small population of New Mexico could only absorb a limited amount of trade goods, so many of those who followed in Becknell’s footsteps were forced to continue to Chihuahua to sell their wares, where they were met by resistance both from Mexican merchants.

In March 1825, President John Quincy Adams appointed three commissioners to mark a road to Santa Fe and negotiate a treaty with the Osage Indians for a right of way. These commissioners were Benjamin Reeves of Missouri, Thomas Mathers of Illinois, and Major George C. Sibley, an Indian agent at Fort Osage on the Missouri River. Sibley became the head of the expedition and was aided by William Becknell in mapping the trail for the surveyors.

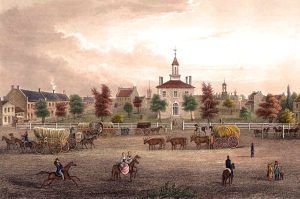

Fort Osage, Sibley, Missouri

In April 1825, the expedition set out from Fort Osage, Missouri. On a tributary of the Neosho River, the commissioners met with the leaders of the Kanza and Osage tribes, negotiating agreements for safe passage. Sibley noted the occasion by naming a nearby copse of oak trees “Council Grove.” Today, the town of Council Grove, Kansas, stands on this location.

The party then continued to the Arkansas River and followed it to the 100th Meridian, the contemporary border with New Mexico. As part of the survey, the group erected mounts to guide travelers from Fort Osage to this point. They waited here for approval to enter Mexico, which they received in late September. Then, Sibley pushed on toward Santa Fe, and the other commissioners returned to Missouri.

The reduced party followed the north bank of the Arkansas River for about 40 miles, crossing at a ford. After following the river a few more miles, Sibley led them south toward the Cimarron River. Their path roughly traced what would later become known as the Cimarron Cutoff, bisecting the corner of the present Oklahoma Panhandle. After suffering from lack of water in what became known as the “Cimarron Desert,” the party reached Taos, New Mexico.

The group was treated warmly by the local government and eventually received permission to survey the route in New Mexico. However, the other commissioners never arrived, and in August 1826, the group returned to Missouri. After several delays, the commissioners submitted their report in October 1827. However, the survey had little impact because the constant traffic to Santa Fe had by 1827 left a clear path for others to follow.

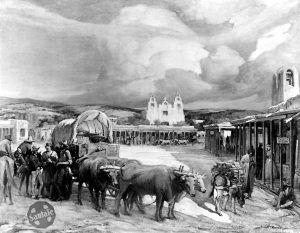

Independence, Missouri Square, 1855

In 1827, the town of Independence, Missouri, was founded and, by 1832, would become the eastern terminus and outfitting point for the Santa Fe Trail.

In addition to the challenges of competition and lack of water in the “Cimarron Desert,” Santa Fe Traders faced another problem — an increase in Indian attacks. In 1827 Pawnee Indians in Kansas made off with more than 100 mules and other livestock from a wagon train returning from New Mexico. The following year, several Pawnee warriors killed two members of a wagon train. In retribution, the traders shot and killed a group of presumably innocent Indians in the area. Thus began a period of harassment by the Indians of wagon trains along the trail, and soon U. S. troops were enlisted to accompany wagon trains across the Great Plains, with Mexican troops meeting them at the Arkansas River, which was, at the time, the international border between the United States and Mexico.

The Cimarron Route was the only wagon road to Santa Fe until the 1840s, when the Mountain Branch was opened.

1829 – 1830

In 1826 and particularly in 1828, Extensive Missouri River flooding destroyed Franklin as the primary Santa Fe Trail jumping-off spot. In addition, steamship traffic encouraged upriver development, and during this transition period, westbound trading caravans began leaving from a variety of locations, including New Franklin, Fayette, Lexington, and Independence, Missouri. The mileage from Lexington to Santa Fe was 837 miles.

In 1929, military escorts began traveling with the traders because of the increase in Indian attacks. The first was under the command of Major Bennett Riley, who escorted a Santa Fe Trail wagon train to the Mexican border, which, at that time, was in the vicinity of present-day Dodge City. This army escort used the first oxen on the Trail, and these animals proved to be better able to withstand the hardships of trail travel, were less attractive to the Indians to steal, and could be eaten if needed.

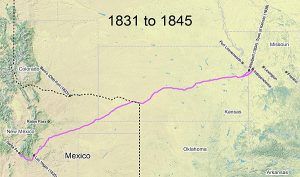

1831 – 1845

By 1831, Independence, Missouri had grown into a substantial town. Given an improved connection between Independence and two Missouri River landings, the city captured most of the Santa Fe Trail traffic during this period. Rival Westport (Kansas City), Missouri, was founded in 1832, and by the mid-1830s, nearby Westport Landing was attracting a small but increasing portion of the New Mexico trade. The trail length from Independence to Santa Fe via the Cimarron Route was 800 miles.

In 1833 a cavalry unit named the United States Dragoons was organized to fight Indians in the West, and the Santa Fe Trail became one of their most important routes.

Also occurring in 1833 was the establishment of Bent’s Fort (Fort William) on the upper Arkansas River in Colorado. Built as a fur trading post by brothers William and Charles Bent and Ceran St. Vrain. In the summer of 1834, one of their groups, with wagons, eastbound from Santa Fe, New Mexico traveled by way of Taos and Raton Pass to Bent’s Fort; then came down the Arkansas River to the Santa Fe Trail — thus opening the Bent’s Fort branch of the Santa Fe Trail.

After 1839 and until the coming of the railroad in 1880, Mexican entrepreneurs from Santa Fe and Chihuahua were active participants in the trade with the United States, driving their wagon trains over the Trail to Missouri and returning with manufactured goods from the eastern United States and Europe.

In the early 1840s, organized bands of guerrillas began to prey on the trading parties along the Santa Fe Trail. One of these bands was formed in the fall of 1842, under the leadership of one John McDaniel, who claimed to hold a captain’s commission in the Texan army. Early in 1843, McDaniel started for the trail to join his force with that of another Texan bandit named Charles Warfield, who had plundered and burned the town of Mora, New Mexico. Before the two groups joined up, Warfield’s gang was dispersed by a party of New Mexicans. McDaniel’s force robbed and murdered the trader Don Antonio Jose Chavez in the early spring of 1843. When the Warfield band was broken up, some of the stragglers joined Major Jacob Snively, another Texan. These recruits gave Snively a force of some 200 men, with which he met and defeated a detachment of Armijo’s command south of the Arkansas River in Kansas. The unsettled conditions along the trail made a military escort necessary. In May 1843, a train left Independence under the protection of 200 United States dragoons commanded by Captain Philip St. George Cooke. Upon arriving at the Caches, Captain Cooke was visited by Snively, who, with about 100 men, was encamped on the opposite side of the river. The boundary between the United States and Texas had not yet been settled. Still, Cooke took the position that Snively was operating within the territory of the United States, disarmed his men, and ordered them to disband.

In 1844 trader, explorer, and naturalist Josiah Gregg chronicled his trips over the Santa Fe Trail in his popular book Commerce of the Prairies. The two-volume set was an account of his time spent as a trader on the Santa Fe Trail from 1831 to 1840 and included commentary on the geography, botany, geology, and culture of New Mexico. The book established Gregg’s literary reputation.

In 1845, Colonel Stephen Kearny left the Santa Fe Trail east of Willow Springs. He blazed a route northeastward to Fort Leavenworth, ferrying the Kansas River, near the mouth of the Wakarusa River, on flatboats operated by Shawnee Indians. The following year, Kearny would dispatch his Army of the West to New Mexico over this Fort Leavenworth branch of the Santa Fe Trail.

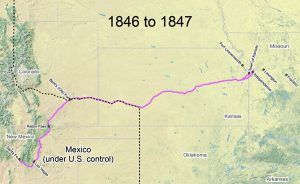

1846 – 1847

In May 1846, the U.S. Congress declared war against Mexico. A month later, General Stephen W. Kearny’s Army of the West left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and by the end of August, his forces had gained control of New Mexico. Indian raids made the Cimarron Route increasingly dangerous, so most trail traffic was diverted to the Mountain Route. From Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, the trail length via the Mountain Route was 844 miles. This new branch of the Santa Fe Trail from Fort Leavenworth was much traveled in 1846, becoming a military supply route. Much-traveled in 1846, the road seems to have had limited use after that, though some ’49ers traveled it. Kearny assured the residents that the army would take care of their “Indian” problems, and military posts were established in New Mexico. During this time, the Mountain Route or Bent’s Fort Route over Raton Pass became popular.

That same year, Susan Shelby Magoffin became the first American woman to travel the Santa Fe Trail. She accompanied her older husband, a well-established American merchant. She wrote of the many hardships along the trail — heat, thirst, mosquitoes, wolves, and a wagon accident in her diary. But, she also wrote enthusiastically about the scenery and the excitement of the journey. In one of her entries, she said simply, “It is the life of a wandering princess mine.” The diary was edited by Stella M. Drumm and published in 1926 under the title, Down the Santa Fe Trail and into New Mexico.

Beginning in 1847, antagonism against the Americans by the Indians and Mexicans made travel on the Cimarron Cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail extremely hazardous.

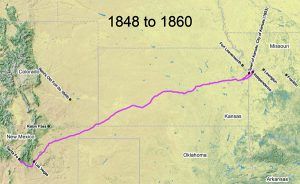

1848 – 1860

In 1848 the Mexican-American War ended. With the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, New Mexico and the surrounding territory were now part of the U.S. Southwest. Military traffic joined commercial traffic along the Santa Fe Trail. The Cimarron Route was again the most commonly-used route to and from Santa Fe. The Town of Kansas (later Kansas City) had supplanted Independence as the predominant eastern trailhead. Trail length from the Town of Kansas to Santa Fe via the Cimarron Route was 788 miles.

On June 19, 1848, 14 people, including Lucien Maxwell, Charles Town, Peter Joseph. About 150 Jicarilla Apache Indians attacked Elliott Lee, Indian George, and two children in Manco Burro Pass, New Mexico, and several of the party were killed or wounded. Nine men and two children survived.

In 1849 the California Gold Rush dramatically increased traffic on the Santa Fe Trail. At that time, Waldo, Hall & Co. held the government contract to carry the United States mail to Santa Fe, a point 700 miles west of the Missouri River. Passenger stage service also began along the trail. Passengers paid $150 for the 25-30 day trip and were required to sleep on the ground at night. The capacity was nine passengers inside and two on top. An army patrol escorted some wagons. The service continued until 1861.

At the same time, new branch trails were established, including one from the Missouri border by way of Fort Scott, Kansas, and another from Harrisonville, Missouri, which joined the Santa Fe Trail east of Council Grove, Kansas. In 1849 and succeeding years, westbound emigrants in increasing numbers, began to use the trail for other purposes, including taking the Mountain Route to the upper Arkansas River in Colorado and then traveling northward by a trail along the base of the Rocky Mountains to the South Platte River, and Fort Laramie, Wyoming.

On October 28, 1849, the White Massacre occurred in northeastern New Mexico along the Santa Fe Trail. James White, a merchant who plied his trade between Independence, Missouri, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, traveled west with a wagon train led by a well-known wagon master, Francois X. Aubrey. After the wagon train passed what was considered the dangerous part of the trip, it encamped. White, “a veteran of the trail,” along with his wife Ann, baby daughter, a servant, and several other men, decided to separate from the train and advance to Santa Fe alone. After a few days of traveling by themselves, they paused at a well-known landmark called the Point of Rocks. Their camp was Jicarilla Apache warriors, Mr. White and 12 other men were killed, and Mrs. White, her daughter, and her servant were kidnapped. Mrs. White was later also killed. Her daughter and servant were never found.

In May 1850, an express stage carrying mail from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to Santa Fe was attacked by Jicarilla Apache and Mohuache Ute Indians near Santa Clara Spring, New Mexico. All of the messengers were killed in a canyon northwest of Wagon Mound. Indian attacks continued through the mid-1850s.

The gold rush to California brought Asiatic cholera to the Great Plains and by 1850 it was epidemic. In Osage County, Kansas, there are unmarked gravesites at Soldier Creek Crossing. The creek was reportedly named after an army unit that suffered heavy losses to cholera at this location in 1851. It is thought these soldiers were part of Brevet Colonel Edwin V. Sumner’s May-June expedition with the First Dragoons, who were headed southwest to establish Fort Union, New Mexico. During their journey, at least 35 men were lost to cholera along the trail between the Kansas River and the crossing of the Arkansas River. However, the vast majority of the Dragoons made it to New Mexico and soon established Fort Union in Mora County to help protect trail commerce.

That same year discovered an alternative to a portion of the Cimarron branch of the trail that avoided the dry Jornada Del Muerto (Cimarron Desert). Although slightly longer, the alternate route, known as the “Aubry Cutoff,” left the Arkansas River further west near present Syracuse, Kansas. It then joined the original trail at Cold Springs, Oklahoma, and continued past Camp Nichols, Oklahoma, before moving into New Mexico.

Wootton Ranch on the Santa Fe Trail

In 1858, the Colorado Gold Rush began, bringing more travelers along the Santa Fe Trail along the Mountain Branch. The following year, Fort Larned, Kansas, was established to protect travelers along the trail. 1859 and 1860, travel became almost impossible because of attacks by the Comanche and Kiowa Indians along the Santa Fe Trail.

The Majors, Waddell, & Russell Freight Company was hauling along the Cimarron Cutoff in the summer and along the Mountain Branch over Raton in the winter until 1860 when they were caught in Raton Pass in a snowstorm. They had to build cabins and camp there until Spring. Dick Wooton later built his tollgate at the cabin site.

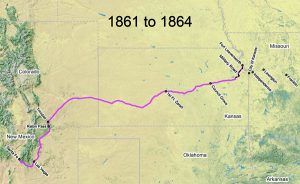

1861 – 1864

With the coming of the Civil War, the activities of border ruffians east of Council Grove made the trail in eastern Kansas unsafe to travel, so most westbound traffic commenced from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Due to dangers from Indian raids, most people traveled over the Mountain Route. The trail length from Fort Leavenworth to Santa Fe was 834 miles — 49 miles on Fort Leavenworth Military Road and 785 miles on the main trail. In 1862, the Battle of Glorieta Pass took place in Northeast New Mexico, holding the southwest for the Union.

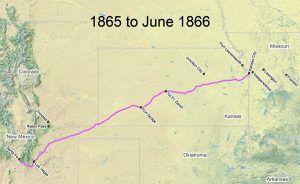

1865 – 1866

After the Civil War, traffic over the trail returned to its prewar pattern. The trail began or ended in Kansas City, and most traffic used the Cimarron Route. The trail length from Kansas City to Santa Fe via the Cimarron Route was 788 miles.

In 1865 Richens Lacy “Uncle Dick” Wootton built a 27-mile toll road over Raton Pass, with a tollgate just north of the Colorado State line. The Colorado Territorial Legislature passed an act to incorporate the Trinidad and Raton Mountain Wagon Road Company on February 20, 1865. Until Wootton built the road, the route across the pass had been in terrible condition, and it took five days to travel the 27 miles. The road made 18 steep crossings of Raton Creek.

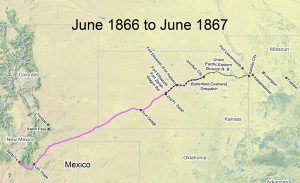

1866 – 1867

Though the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad began to be built west from the Kansas City area in 1863, the rails didn’t reach Junction City and Fort Riley until June 1866. When it did, he, long wagon trains that had previously formed at Council Grove, now formed at Junction City and moved westward over the Smoky Hill route. The Stage Company moved its entire outfit from Council Grove to Junction City. The caravans moved west to Fort Ellsworth, then southwest on a connecting road to Fort Zarah (Great Bend, Kansas), where they resumed the main trail. The long-distance Santa Fe Trail traffic east of Fort Zarah slowed to a trickle. The trail length from Junction City to Santa Fe was 699 miles — 76 miles from Junction City to Fort Ellsworth, 40 miles from Fort Ellsworth to Fort Zarah, and 583 miles from Fort Zarah to Santa Fe. Over the next few years, as the railroad continued to expand westward, the Santa Fe Trail would shorten at its eastern end. Between 1866 and 1867, a cholera epidemic decimated many U.S. cities. About 200 a day died in St. Louis, Missouri, during the height of the epidemic.

In 1866, Barlow & Sanderson’s Southern Overland Mail & Express Co. received the mail contract and started running stage service between Kansas City and Santa Fe weekly. Home and swing stations were built, and the trip took 13 days. The following stage stops along the Mountain Branch were made in the Raton and Springer area of New Mexico:

- Willow Spring – Water stop and emergency station.

- Clifton House (Stockton Station, Red River Station) – Home station (where the passengers got food and lodging for the night), corrals, and blacksmith shop.

- Crow Creek – Swing station (where the stock tenders changed the horses).

- Verrnejo – Swing station.

- Cimarron – Home station, stables.

- Rayado – Swing (?) station, a seven-room hotel lay on the west side of Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail on the south side of Ocate Creek near present Calhoun Cemetery. Wild Bill Hickok reportedly drove a stagecoach over Raton Pass for Barlow, Sanderson & Co. The company ran stages from the end of the track as the railroad was extended westward. In 1872, the firm’s name was changed o Barlow and Sanderson Co. The freighting business also was forced to gradually move westward from the end of the track. After the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad reached the east end of the Cimarron Cutoff in western Kansas in 1872, the cutoff was no longer used, and the Aubrey Route or the Mountain Branch was used. Probably about this same time, Mathias Heck opened a stage station and store at the crossing of Sweetwater Creek on the Mountain Branch south of Rayado.

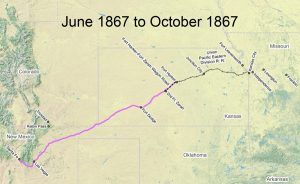

1867

The Union Pacific Railroad reached Fort Harker, Kansas (near Fort Ellsworth) in June 1867. For the next several months, most Santa Fe-bound travelers began their trail trips at this point. The trail length from Fort Harker to Santa Fe was 623 miles – 40 miles from Fort Harker to Fort Zarah and 583 miles from Fort Zarah to Santa Fe.

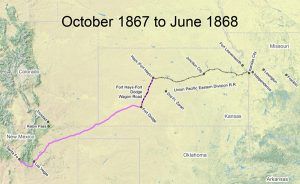

1867 – 1868

The Union Pacific Railroad reached Hays City (near Fort Hays) in October 1867, after which wagons and stagecoaches used this point to begin their westward trips. Most long-distance trail traffic stopped east of Fort Dodge, Kansas. The trail length from Hays to Santa Fe was 568 miles: 75 miles from Hays to Fort Dodge and 493 miles from Fort Dodge to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Beginning in the fall of 1867, Barlow, Sanderson, and Co. ran stages from Hays City, Kansas, to Santa Fe.

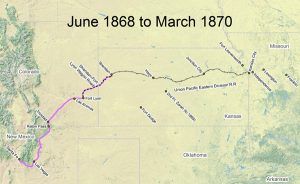

1868 – 1870

The Union Pacific Railroad tracks reached the town of Sheridan, Kansas, in June 1868, and then westbound freight headed southwest over a wagon road to Fort Lyon, Colorado, on the main trail. The Cimarron Route was abandoned after June 1868, and most long-distance Mountain Route traffic ceased east of Fort Lyon. The trail length from Sheridan to Santa Fe was 428 miles — 120 miles from Sheridan to Fort Lyon and 308 miles from Fort Lyon to Santa Fe.

In 1869 Barlow, Sanderson & Co.. began running a connecting stage line from Denver, Pueblo, and Trinidad, Colorado. ln June 1869, the Southern Overland Mail Co. started tri-weekly service to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

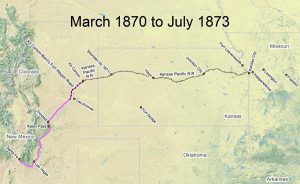

1870 – 1873

The Kansas Pacific (formerly the Union Pacific Railroad) reached Kit Carson, Colorado, in March 1870. The primary connecting route between there and the main Santa Fe Trail was a 66-mile freight route that went southwest to the site of Bent’s Old Fort. The trail length from Kit Carson to Santa Fe, via the freight route, was 358 miles — 66 miles from Kit Carson to Bent’s Old Fort site and 292 miles from the fort site to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

1873

A new railroad — the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, was also building west from eastern Kansas and began to compete for Santa Fe Trail traffic in July 1873 when it reached Granada, in eastern Colorado. Most trail traffic began running over the Granada-Fort Union wagon road, although some traffic continued through Trinidad. The trail length from Granada to Santa Fe was 323 miles — 224 miles on the connecting road and 99 miles along the main trail right of way. The days of the Santa Fe Trail as the main transportation route were over.

1873 – 1875

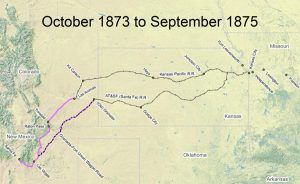

The Kansas Pacific Railroad, in a bid to stay competitive with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, completed a 58-mile spur line in October 1873 from Kit Carson to Las Animas, Colorado, located adjacent to the Santa Fe Trail. For the next two years, significant trail traffic continued to move over two separate routes. The trail length from Las Animas to Santa Fe was 304 miles.

1875

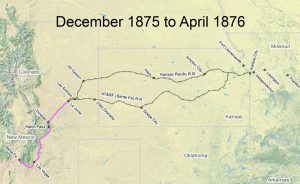

In September 1875, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad tracks reached Las Animas, Colorado, and for the next several months, both railroads had railheads in the same town. Virtually all Santa Fe Trail traffic now went over the main route via Raton Pass, and the Granada-Fort Union wagon road, as far as Santa Fe Trail traffic was concerned, was abandoned. The trail length from Las Animas to Santa Fe was 304 miles.

1875 – 1876

Kansas Pacific track crews, building westward from Las Animas, reached the boomtown of La Junta in mid-December 1875, and within two weeks, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad tracks reached there as well. For the next several months, both railroads were equally competitive to serve points in southeastern Colorado. The trail length from La Junta to Santa Fe was 285 miles.

1876 – 1878

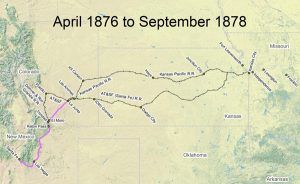

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad tracks railroad track crews, building westward from La Junta, reached Pueblo in March 1876. Just one month later, the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad completed a line south from Pueblo to El Moro (5 miles northeast of Trinidad). As a result, mail traffic and some stage passengers began their Santa Fe Trail journey south from El Moro, but Santa Fe-bound freight traffic continued to run southwest from La Junta. The trail length from El Moro to Santa Fe was 207 miles.

1878 – 1879

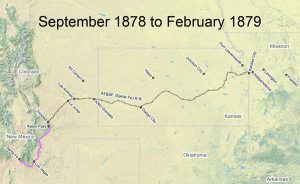

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad tracks reached Trinidad in September 1878. Construction of this line had begun at La Junta in May, following a February confrontation south of Trinidad that resulted in Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad tracks crews gaining the right to build over Raton Pass. Santa Fe’s victory at Raton Pass eliminated the Kansas Pacific as a railroad competitor. The Kansas Pacific route between Kit Carson, Las Animas, and La Junta was abandoned soon afterward. The Santa Fe Railroad bought “Uncle Dick” Wootton toll road to use for the train. Santa Fe was 202 miles.

1879

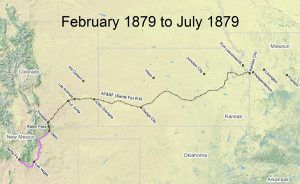

Santa Fe tracks reached the top of Raton Pass and entered New Mexico on November 30, 1878; the first locomotive came over Raton Pass on December 7, 1878. In February 1879, crews extended the tracks to Otero. Near the old Clifton House stage station (just south of present-day Raton), this impromptu camp served as the temporary railhead while construction crews pushed toward Las Vegas, New Mexico. The trail length from Otero to Santa Fe was 176 miles. On July 7, 1879, a tunnel was completed under the pass. The use of the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail significantly decreased.

1879 – 1880

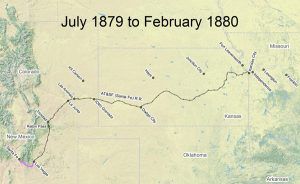

Santa Fe railroad tracks reached Las Vegas, New Mexico, on July 1, 1879, and the first train entered the city three days later. Las Vegas served as the railhead and eastern trail terminus for the last few months that the Santa Fe Trail served as a long-distance route. The trail length from Las Vegas to Santa Fe was 64 miles.

1880

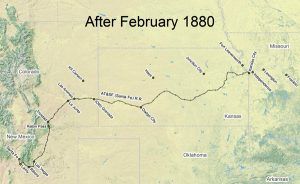

The first Santa Fe railroad train entered Santa Fe, New Mexico, on February 9, 1880, via an 18-mile spur track that Santa Fe County voters had funded in an October 1879 bond election. The entire 835-mile Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail, from Kansas City to Lamy and Santa Fe, could now be traversed by rail. After this date, the Santa Fe Trail either served local needs or fell into disuse.

In 1906, the Daughters of the American Revolution began erecting Trail markers. In 1985, the Santa Fe Trail Association was formed to help preserve and promote awareness and appreciation of the trail. Two years later, in 1987, Congress designated the Santa Fe National Historic Trail under the National Trails System Act.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

Tails and Trails of the American Frontier

Sources:

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture

History of the Santa Fe Trail & William Becknell

New Mexico History

Santa Fe National Historic Trail

Santa Fe Trail Association

Santa Fe Trail History