By William Francis Bailey in 1906

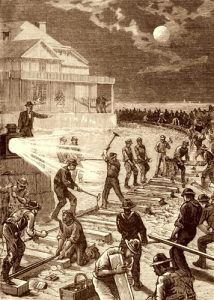

By the terms of the supplementary Charter of 1864, a great incentive was given to the two Companies, the Union Pacific Railroad and the Central Pacific Railroad, to get down as great a mileage as possible. In addition to the Government grant of Land and Bonds based on mileage, there was the traffic of the Mormon country and Salt Lake City at stake. Besides this, it was readily seen that the line having the greatest haul would correspondingly benefit when subdividing earnings on trans-continental business. With these incentives, both companies put forth every effort to cover the ground. In the early part of 1869, the rails of each Company were going down from six to ten miles a day. Records in track-laying were made then that have never been broken. Near Promontory, a still-standing sign announces “Ten miles of track laid in one day.”

Actual figures are not obtainable, but reliable contemporaries at that time stated there were twenty-five thousand men employed on the construction of the two lines and 6,000 teams, and 200 construction trains. Both Companies were anxious to establish a point of advantage that they could use in the controversy that was inevitable and which would determine the mileage and territory each was to enjoy.

On April 29th, nine and a half miles remained unfinished. Three and a half for the Central Pacific Railroad, they having laid ten miles the day before, and six miles for the Union Pacific Railroad, the latter being the ascent of Promontory Hill and including a stiff bit of rock work. When the two tracks came together, the Central Pacific Railroad had nearly 60 miles of grading parallel to the Union Pacific Railroad track—from Promontory east to the mouth of Weber Canon. In contrast, the Union Pacific Railroad had located their line to the California State line, and most of the grading was done as far west as Humboldt Wells, Nevada, four hundred and 50 miles from Ogden.

As stated, the two tracks were brought together at Promontory, Utah, on May 9th, 1869. Still, two rail lengths were kept open until the issues’ questions were adjusted and a suitable program could be arranged for celebrating the event. Everything satisfactorily arranged, Monday, the 10th of May 1869, was set for the ceremonies.

The Central Pacific Railroad completed its track up to Promontory on May 1st. It was the intention to have the opening ceremonies on Saturday, May 8th, and the Central Pacific officials were on hand for that purpose. The Union Pacific party coming west was delayed some 48 hours at Piedmont by a gang of graders and track-layers, who, not having received their wages, sidetracked the special train with Vice-President Durant and his party, holding them as hostages until the Company had paid over to the contractor some two hundred and fifty thousand dollars due him and which he in turn distributed among his men.

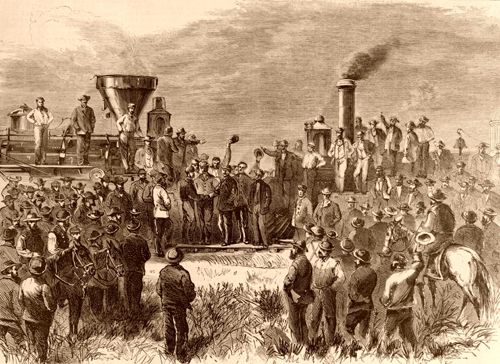

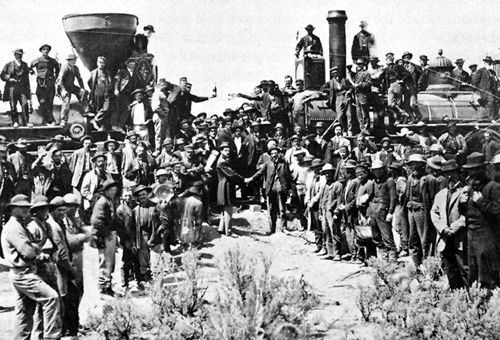

As early as 8:00 A.M. on the 10th, the spectators, mostly workmen of the respective companies or other citizens of the railway camps, commenced arriving. At 8:45, a special over the Central Pacific Railroad came in with many passengers. At 9:00, the Union Pacific Railroad contingent arrived in two trains, and at 11:00, the Central Pacific Railroad’s second train, carrying President Stanford and other officers of that Company and their guests, completed the party. About 1,100 people were present, including a detachment of the 21st United States Infantry and its band from Fort Douglass, Utah.

The Chinese laborers of the Central Pacific Railroad soon leveled the gap preparatory to putting down the ties, and all but one rail length was finished. Then Engines Number 119 of the Union Pacific Railroad and No. 60, the “Jupiter” of the Central Pacific Railroad, were brought up to either side of the gap. These engines were gaily decorated with flags and evergreens in honor of the occasion. The Reverend offered a suitable prayer. Dr. Todd of Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The remaining ties were then laid, the last one being of California Laurel finely polished and ornamented with a silver plate bearing the inscription “The last tie laid on the Pacific Railroad, May 10th, 1869”, with the names of the directors of the Central Pacific Railroad and that of the donor.

This tie was put in position by Superintendents Reed of the Union Pacific Railroad and Strawbridge of the Central Pacific Railroad, and was taken up after the ceremonies and has since then been on exhibition in the Superintendent’s office of the Southern Pacific Company at Sacramento, (California) Depot.

For the closing act, California presented a spike of gold; Nevada one of silver; Arizona one of combined iron, gold, and silver; and the Pacific Union Express Company, a silver maul. At twelve noon at a given signal, Governor Stanford on the South side of the rail and Vice-President Durant on the north struck the spikes, driving them home.

The two engines were then moved up until they touched, and a bottle of wine was poured over the last rail as a libation. The trains of the respective roads were then run over the connecting link and back to their own lines. Speeches and a banquet closed the occasion.

In the Crocker Art Gallery in Sacramento hangs a large oil painting of the meeting of the two engines. The artist having inserted actual portraits of many of the more prominent officials of the two lines who participated in the ceremonies.

By previous arrangement, the strokes on the final spikes were to be signaled over all the wires of the several telegraph companies through the United States, business being suspended for this purpose. First, the message was sent over the wires “Almost ready. Hats off; prayer is being offered.” Then “We have got done praying; the spike is about to be presented.” Seven minutes later, “All ready now; the spike will soon be driven.” The signal will be three dots for the commencement of the blows. Connection being made between the hammers and the wires, the blows on the spikes were flashed over practically the whole telegraph system of the United States. At 2:47 P.M. Washington time, 12:47 P.M. Promontory local time, came the signal “Done” and the bells of Washington, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and hundreds of other cities and towns announced that the American continent had been spanned, that through rail communication was established, never to be broken, that the Union Pacific Railroad was completed.

The formal announcement to President Grant and through the Press Associations to every inhabitant of the civilized world was couched in the following language:

Promontory Summit, Utah, May 10th, 1869.

“The last rail is laid, the last spike driven. The Pacific Railroad is completed. The point of junction is ten hundred and eighty-six miles west of the Missouri River and six hundred and ninety miles east of Sacramento City.”

Leland Stanford, Central Pacific Railroad.

T. C. Durant,

Sidney Dillon,

John Duff, Union Pacific Railroad.

No sooner were the ceremonies complete than there was a rush made to obtain souvenirs. In ignorance of the fact that the “Last Tie” had been taken up and an ordinary one substituted, the relic hunters carried off the substitute piecemeal. In fact, some half dozen “last ties” were so taken in the first six months after the roads were completed.

An odd coincidence occurred at the closing ceremonies. The rail on the east was brought forward by the Union Pacific laborers—Europeans, that on the west by Chinese, both gangs having Americans as bosses. Consequently here were Europe, Asia, and America joining in the work, the Americans dominating.

Next morning the Union Pacific Railroad brought in from the East half a dozen passenger coaches for the Central Pacific Railroad, these being attached to the special train of Governor Stanford when he was returning to California, constituting the first through equipment.

All over the land, the different cities vied with one another in celebrating the event—which it truly felt marked the beginning of a new epoch in the history of the United States.

New York City celebrated with the “Te Deum” being sung in “Trinity,” the chimes ringing out “Old Hundred” (Praise God from whom all blessings flow), and a salute of a hundred guns fired by order of the Mayor.

Philadelphia rang the “Liberty Bell” and all fire alarm bells.

Chicago had a parade four miles long, the City being lavishly decorated, and Vice-President Colfax speaking in the evening.

Omaha ad the biggest day in its history: a hundred guns when the news came. A procession embracing every able-bodied man in the town, in the afternoon. Speeches, pyrotechnics, and illuminations in the evening.

At Salt Lake, the Mormons and Gentiles held a love feast in the Tabernacle and decided to build a few railroads for themselves.

San Francisco could not wait until the 10th. They started the evening of the 8th when it was announced at the theaters the two roads had met, and it took two good solid days of celebrating to satisfy the people of that town.

It was rightly felt that the completion of the line was an event in the history of our country. It marked the progress of the West and united the Pacific Coast population with that of the East. It was the commencement of the end of the Indian troubles—assured the settlement of the West and the development of its mines and other resources.

There have been but three general celebrations held in this country over works of public improvement: the Erie Canal, Atlantic Cable, and the Pacific Railroad. Of the three, the latter was by far the more general.

The Poem by Bret Harte on this event is reproduced below:

What the Engines Said.

What was it the engines said,

Pilots touching head to head.

Facing on the single track,

Half a world behind each back.

This is what the engines said,

Unreported and unread.

With a prefatory screech,

In a florid Western speech,

Said the engine from the West,

“I am from Sierra’s crest,

And if Altitudes’ a test,

Why I reckon its confessed,

That I’ve done my level best.”

“Said the engine from the East,

They who work best, talk the least,

Suppose you whistle down your brakes,

What you’re done is no great shakes.

Pretty fair, but let our meeting,

Be a different kind of greeting,

Let these folks with champagne stuffing,

Not the engines do the puffing.

“Listen where Atlanta beats,

Shores of-snow and summer heats.

Where the Indian Autumn skies

Paint the woods with wampum dyes.

I have chased the flying sun,

Seeing all that he looked upon,

Blessing all that he blest.

Nursing in my iron-breast;

All his vivifying heat.

All his clouds about my crest

And before my flying feet

Every shadow must retreat.”

Said the Western Engine, “phew!”

And a long whistle blew,

“Come now, really that’s the oddest

Talk for one so modest.

You brag of your East, you do,

Why, I bring the East to you.

All the Orient, all Cathay

Find me through the shortest way

And the sun you follow here

Rises in my hemisphere.

Really if one must be rude,

Length, my friend, ain’t longitude.”

Said the Union, “don’t reflect, or

I’ll run over some director,”

Said the Central, “I’m Pacific

But when riled, I’m quite terrific,

Yet today we shall not quarrel

Just to show these folks this moral

How two engines In their vision

Once have met without collision.”

That is what the engines said;

Unreported and unread,

Spoken slightly through the nose

With a whistle at the close.’

The first through train reached Omaha on May 6th, arriving in two sections and bringing about five hundred passengers.

Although through trains were on a regular schedule commencing with May 11th, it was not until November 6th, 1869, that the road was completed (according to Judicial decision.) Congress to make sure of the fact, authorized the President by resolution passed April 10th, 1869, to appoint a board of five “eminent” citizens to examine and report on the condition of the road and what would be required to bring it up to first class condition. This board duly reported in October 1869 that the line was all right but that a million and a half could be spent to advantage in ballasting, terminal facilities, depots, equipment, etc. On the strength of which the wise acres decided the road could not be considered complete and withheld a million dollars worth of bonds due under the charter act. It was October 1st, 1874, before the fact that the line was completed sifted through departmental red tape. The Secretary of Interior, on the further report of “three eminent citizens,” discovered that the road had been completed November 6th, 1869, as reported by the previous board of five, and further that the total cost of the line had been one hundred and fifteen million, two hundred and fourteen thousand, five hundred and eighty-seven dollars and seventy-nine cents, as shown by the books of the Company.

For a while, business was interchanged at Promontory, but it was but a short time until the two companies got together. An agreement was reached by which Ogden should be the terminus and that the Central Pacific Railroad Company should purchase at a cost of two million, six hundred and ninety-eight thousand, six hundred and twenty dollars the line from a point five miles west of Ogden to the connection at Promontory. This five miles was subsequently sold to the Central Pacific Railroad. This arrangement was, as the West puts it, “clinched” by a Resolution of Congress, making Ogden the terminus.

William Francis Bailey, 1906. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexanderer/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Author & Notes: This tale is adapted from a chapter of a book written by William Francis Bailey, entitled The Story of the First Trans-Continental Railroad: Its Projectors, Construction and History, published in 1906, by the Pittsburgh Printing Co. The tale is not 100% verbatim, as minor grammatical errors and spelling have been corrected.

Also See:

A Century of Railroad Building

The Alpine Tunnel – An Engineering Marvel

Frontier Era Time Capsule– (Johnson Canyon Rail Tunnel)

Indian Troubles During Construction