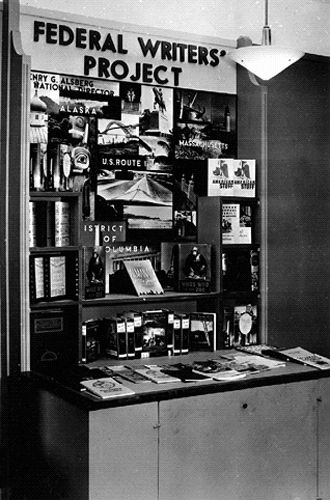

By the Federal Writer’s Project in 1938

Interview with Captain W. H. Hembree:

On April 28, 1938, Captain W. H. Hembree, who was then working in a gold mine near Estacada, Oregon, was interviewed by the Andrew C. Sherbert of the Federal Writer’s Project for his knowledge of pioneering days and what he might know about the legend of the Lost Blue Bucket Mine. At that time, Captain Hembree was 73 years old and described by Mr. Sherbert as short, stocky, extremely rugged, and with the appearance of great physical capabilities for one his age. Sherbert also stated that Hembree was knowledgeable in the various methods used in recovering gold and at the time, had the appearance of a typical prospector, complete with carrying ore samples and a magnifying lens in his pocket.

Hembree’s Words:

I was born in Monmouth, Polk County, Oregon, on October 7, 1864, and was christened by William Harry Hembree. My father’s name was Houston Hembree. He was named after the illustrious Sam Houston and was born in Texas, though his family later moved to Missouri. My mother’s name was Amanda Bowman, and she was born in Iowa, and coming to Oregon in 1848. My father left Missouri for Oregon in one of the first emigrant trains of the great migration of the 1840s, arriving in the Willamette Valley sometime in 1843. The train my father came to Oregon with is said to have been the first “wheels” ever to make the entire journey from the east to The Dalles.

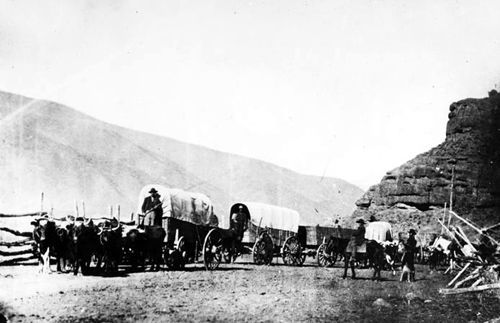

Wagon train

The wagon train of which my father and his kinfolks were members was more fortunate than the parties which followed the old Oregon Trail in the years immediately after. The Indians did not trouble the earlier emigrants, were friendly in fact, according to accounts given to me by my father. It was not until the later emigrants came through that the Indians began to attack travelers — in 1844, 1845, and thereafter. Father’s train arrived at The Dalles with exactly the same number of members as it had when it left Missouri. There had been, however, a death and a birth on route, both occurring simultaneously at a place now called Liberty Rock, Idaho. The one who died was a second cousin of mine, whose name I have forgotten. The child that was born, was my aunt, Nancy Hembree.

Though there had been gold stampedes, land grants from the government, and all sorts of empire-building activities in Oregon after my father arrived from the east, he had not yet struck it rich when I squalled onto the scene 10 years later. When I am asked to recall incidents of my early life and to describe the games we played in my childhood, I can truthfully answer that there was no childhood, in the sense meant. There were no games. All that I remember about my childhood is work, work, and work. Work long before the sun came up. Work, long after the sun had set. When I was eight years old I was doing real labor — labor that today would draw a man’s wages. Union working hours? Sit down strikes? Such things were not dreamed of then.

My father and older brothers used to make shingles every day of the week except Sunday. They made them by hand, driving them out of cedar bolts with a tool called a “frow.” If you’ve never seen one, a frow is a steel, wedge-shaped cleaver-like blade with a sharp edge, with a handle set at right angles from one end of the blade. You hit the frow with a mallet, driving through the shingle bolt, cleaving the bolt with the grain of the wood. Only the best, the very best straight-grained cedar, was used for these shingles. The manufactured shingles of today have a useful life of about ten years or so, but, I’m willing to wager that some of the shingles my family made — if there was any possible way of identifying them — are still giving service somewhere in Oregon. They were made to be practically everlasting.

At the tender age of eight years, I worked with the rest of the men of the family. As the youngest, my job was to keep the shavings all raked up into piles and bundle the shingles as fast as my father and brothers made them. That was no easy job for a youngster so small, for they contrived to fashion a surprisingly large number of shingles each day, and the piles of shavings grew prodigiously large as the day wore on. No sooner would I arrange and tie one bundle of shingles than it seemed another was ready to tie. We used to work well on into the evening. That’s when the piles of shavings were put to use. I would set fire to the shaving piles, one after another, as each burned out, and we worked by the light of these pungent fires. It was not unusual for us to work 14 or 16 hours from when we started in the morning until we gave up and called it a day. I was always a pretty tired youngster when I had tied off the last bundle and was mighty glad when my father would say, “Alright, boys, let’s put out the fire.”

I worked along with the family, riving shingles until I was 12 or 13 years old, when I began to work out for others. Boys in those days seemed to mature earlier than they do now. As soon as a lad had a sign of fuzz on his cheek, he was considered a man and was expected to fill any place that a man could. I was no exception. At 15, I was riding the range, and at 17, had been pretty much all over the great plains of central and eastern Oregon.

As I said before, we worked every day but Sunday, and except for chores, Sunday really was a day of rest and a very welcome one. The day was really a quiet and holy day in those times. My family was not what one would consider overmuch pious or religious, for those times, but, it seemed that every family embraced some sort of faith. God did not seem so far away as he does today. He seemed mighty close to us. We seemed to see evidence of His works all around us and were mightily awed by His power. I noticed that folks, in general, don’t have that sort of religious consciousness in them of late years.

Our home was typical of a pioneer Oregon family. Mother made home-spun. I can see her at the spinning wheel, treading out the yarn that was to go into the things that we would be wearing a few months later. Today, women of the age she was then use the same toe my mother used on the treadle, to step on the accelerator as they drive to a department store for machine-made cloth and ready-made garments. Our work clothes, shirts, and pants, were usually made of home-tanned buckskin. This stuff wore like iron, and though it was not very beautiful to look at, it was extremely serviceable. When a man — and I mean by that, any male person over 16 or thereabouts — was able to accumulate the required number of dollars, one of his most important investments would be in a Sunday-go-to-meeting outfit made by eastern tailors, and consisting of a swallow-tail coat, a fancy, light-colored vest, and a striped pair of pants. He would top this elegant attire with a high, beaver hat. He was then ready for — and considered properly dressed to be acceptable in — the most dignified and formal gathering, or social function.

After a good deal of wandering about, mostly within Oregon’s boundaries, I came to Portland and got a job in Portland’s “Paid” fire department. The fire department personnel, at that time, comprised both paid and volunteer firemen. I stayed with the department for about three years, making an excellent record as a fireman, and then went to sea as a sailor. I liked the seafaring life very much, and my travels took me to many foreign ports, where I saw a great deal to interest a young man of my active and curious disposition. But, I hadn’t quite forgotten the thrill and excitement that went with fighting fires, so I returned to Portland, and because I had left a good service record behind me when I quit the department previously, I was immediately placed on the roster and became once more a fireman. After another few years as a fireman, the sea beckoned again, and I returned to walk the caulked planks of a ship’s deck. A couple of years at sea and I again found myself yearning for the prancing fire-horse and clanging gong. Back to the fire department, where I served during Mayor Simon’s administration, quitting finally and never again returning because of disgust with political wrangling going on within the department’s ranks. I then worked on riverboats in various capacities, where I earned the courtesy title of Captain. I have no papers, however.

In between other activities, even as a young man I was interested in gold mining. I have prospected in the past 50 years in almost every section of Oregon where gold had been or appeared that it might be found. I have panned every river and creek in the state where I thought there was a remote possibility of making worthwhile findings. In recent years, I have operated small mines with more or less success. I am, at present, beginning the operation of a mine in Clackamas County, near the Marion County line. The sample essay looks good, and in spite of many former disappointments in similar enterprises, I have every hope that this one will turn out prosperously. However, if it doesn’t, I shall promptly find another likely-looking hole-in-the-ground, and with a true prospector’s unquenchable optimism, my hopes will doubtless rise again.

Perhaps the most widely publicized Oregon gold mine, if there ever was such a mine, is the famous “Blue Bucket.” I have been erroneously credited with knowing a great deal about this mysterious, lost mine. As a matter of fact, in common with many other persons, I have been tremendously interested in the historic “Blue Bucket”; have gathered a considerable amount of data concerning it, and have journeyed to the region where it was supposed to have been located. I might even go so far as to say that I am satisfied in my own mind that I have been to within a few furlongs of the actual spot where it was. However, until the elusive “Blue Bucket” is actually and indisputably rediscovered, one man’s story is as good as another’s.

Here’s Mine:

The Blue Bucket Mine got its name from the fact that a wagon train which is supposed to have stumbled onto the rich gold deposit, was made up of a string of wagons, the bodies of which were painted blue. In those days, wagons had no hub nuts to hold a wheel in place on the axle. Wheels were held on the axle by a linch pin, merely a pin or bolt, that slipped through a hole in the axle outside the hub of the wheel. Between the hub and pin was a washer that rubbed on the hub. To prevent wear, it was necessary to constantly daub the axle, at the point of friction, with tar, which the immigrants carried in buckets that hung on a hook at the rear of the wagon. The tar buckets of this particular wagon train were also painted blue. The train made a “dry camp” (no water in sight) one night on a meadow in a valley between two ridges of hills. Needing water for their horses, members of the train set out on foot, each in a different direction, to attempt to locate a small creek or pond nearby. Each carried one of the blue tar buckets to carry water if any were found. One member came upon a wet, cozy spot where it appeared water was near the ground’s surface. He dug down, using the bucket as a spade, and upon raising the bucket, found it filled with wet dirt containing nuggets of gold. And that was how the Blue Blue Bucket Mine was discovered.

I was privileged once to see a diary said to have been kept by a man whose name, I believe, was Warren. The man was a member of the “Blue Bucket” train. In the diary, he kept a day-by-day log of the train’s progress. By a series of calculations, based upon the mileages and directions given in the diary, I was able to reach a position that must have been in the vicinity of the fabulous mine. To further convince myself that I had found the mine’s exact location in my search, I one day stumbled onto a weathered portion of a wagon box, with unmistakable traces of blue paint still visible on its bleached boards. That the wagon box was of the wagon-train era, as evidenced by the foot that it was built like a scow, or flatboat, and was caulked with rags, fragments of which were still intact. Emigrant wagons were constructed in such a manner to permit them to ford streams handily without damaging their contents.

Well, there’s my story of the Blue Bucket Mine. Many think the mine never existed. I think it did; however, I realize that my story would carry far more conviction were I able to exhibit a few buckets of gold taken from it — regardless the color of the buckets.

By William Harry Hembree, 1938.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

About This Article: Part of the Life Histories from the Folklore Project, WPA Federal Writers’ Project of 1936-1940, this interview with Captain William Harry Hembree was conducted by Andrew C. Sherbert in 1938. As it appears here, the interview is not entirely verbatim, as minor editing has occurred. However, the context remains essentially the same.

Also See: