A Battle in the Air

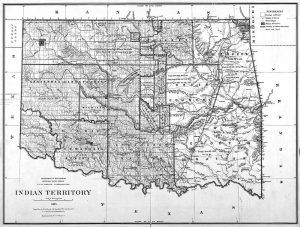

In the country about Tishomingo, Indian Territory (Oklahoma), troubles are foretold by a battle of unseen men in the air. Whenever the sound of conflict is heard it is an indication that many dead will lie in the fields, for it heralds battle, starvation, or pestilence. The powerful nation that lived here once was completely annihilated by an opposing tribe, and in the valley, in the western part of the Territory, there are mounds where hundreds of men lie buried. Spirits occupy the valley, and to the eyes of the Indians, they are still seen, at times, continuing the fight.

In May 1892, the last demonstration was made in the hearing of John Willis, a U.S. Deputy Marshal, who was hunting horse thieves. He was belated one night and entered the vale of mounds, for he had no scruples against sleeping there. He had not, in fact, ever heard that the region was haunted. The snorting of his horse in the middle of the night awoke him and he sprang to his feet, thinking that savages, outlaws, or, at least, coyotes had disturbed the animal. Although there was a good moon, he could see nothing moving on the plain. Yet the sounds that filled the air were like the noise of an army, only a trifle subdued as if they were borne on the passing of wind. The rush of hoofs and of feet, the striking of blows, the fall of bodies could be heard, and for nearly an hour these fell rumors went across the earth. At last, the horse became so frantic that Willis saddled him and rode away, and as he reached the edge of the valley the sounds were heard going into the distance. Not until he reached a settlement did he learn of the spell that rested on the place.

— By Charles M. Skinner in 1896

The Comanche Rider

The ways of disposing of the Indian dead are many. In some places ground sepulture is common; in others, the corpses are placed in trees. South Americans mummified their dead, and cremation was not unknown. Enemies gave no thought to those that they had slain, after plucking off their scalps as trophies, though they sometimes added the indignity of mutilation in the killing.

Sachem’s Head, near Guilford, Connecticut, is so named because Uncas cut a Pequot’s head off and placed it in the crotch of an oak that grew there. It remained withering for years. It was to save the body of Polan from such a fate, after the fight on Sebago Lake in 1756, that his brothers placed it under the root of a sturdy young beech that they had pried out of the ground. He was laid in the hollow in his war-dress, with a silver cross on his breast and bow and arrows in his hand; then, the weight on the trunk being released, the sapling sprang back to its place and afterward rose to a commanding height, fitly marking the Indian’s tomb. Chief Blackbird, of the Omaha, was buried, in accordance with his wish, on the summit of a bluff near the upper Missouri River, on the back of his favorite horse, fully equipped for travel, with the scalps that he had taken hung to the bridle.

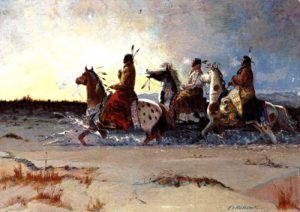

When a Comanche dies he is buried on the western side of the camp, that his soul may follow the setting sun into the spirit world the speedier. His bow, arrows, and valuables are interred with him, and his best pony is killed at the grave that he may appear among his fellows in the happy hunting grounds mounted and equipped. An old Comanche who died near Fort Sill, Oklahoma was without relatives and poor, so his tribe thought that any kind of a horse would do for him to range upon the fields of paradise. They killed a spavined old plug and left him. Two weeks from that time the late unlamented galloped into a camp of the Wichita on the back of a lop-eared, bob-tailed, sheep-necked, ring-boned horse, with ribs like a grate, and said he wanted his dinner.

Having secured a piece of meat, formally presented to him on the end of a lodge-pole, he offered himself to the view of his own people, alarming them by his glaring eyes and sunken cheeks, and told them that he had come back to haunt them for a stingy, inconsiderate lot because the gate-keeper of heaven had refused to admit him on so ill-conditioned a mount. The camp broke up in dismay. Wichita and Comanche journeyed, en masse, to Fort Sill for protection, and since then they have sacrificed the best horses in their possession when an unfriended one journeyed to the spirit world.

— By Charles M. Skinner in 1896

The Legend of the Cherokee Rose (nu na hi du na tlo hi lu i)

“We are now about to take our leave and kind farewell to our native land, the country that the Great Spirit gave our Fathers, we are on the eve of leaving that country that gave us birth…it is with sorrow we are forced by the white man to quit the scenes of our childhood… we bid farewell to it and all we hold dear.”– Charles Hicks, Tsalagi (Cherokee) Vice Chief on the Trail of Tears, November 4, 1838

More than 175 years ago, gold was discovered in the mountains of North Carolina and Georgia and as thousands of new settlers invaded the area, it spawned tensions with the American Indian tribes. As a result, President Andrew Jackson established the Indian Removal Policy in 1830, which forced the Cherokee Nation to give up its lands east of the Mississippi River and migrate to Indian Territory.

The forced march, which began in 1838, was called the “Trail of Tears,” because over 4,000 of the 15,000 Indians died of hunger, disease, cold, and exhaustion. In the Cherokee language, the event is called Nunna daul Tsuny — “the trail where they cried.”

Along the way, the Cherokee mothers cried and the elders prayed for a sign that would lift their spirits to give them strength. One night along the trail, the old men spent the evening in powerful prayer, asking the Great One to help them with their suffering and save the children to rebuild the Cherokee Nation.

The Great One responded to the elders by saying: “Yes, I have seen the sorrows of the women and I can help them to keep their strength to help the children. Tell the women in the morning to look back where their tears have fallen to the ground. I will cause to grow quickly a plant, which will grow up and up and fall back down to touch the ground where another stem will begin to grow.

The next day when the Cherokee continued their journey, the elders advised the mothers to look behind them. In each place where the mother’s tears fell, a beautiful white rose began to grow. As the women watched the beautiful blossoms form, they forgot to cry and felt strong. By the afternoon they saw many white blossoms as far as they could see.

Its rose’s gold center is said to represent the gold taken from the Cherokee lands, and its seven leaves on each stem signify the seven Cherokee clans. Today, the wild Cherokee Rose can be found all along the Trail of Tears from North Carolina to Oklahoma.

Compiled and edited Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2021.

Also See:

Native American Legends & Tales