By Frederick Webb Hodge, 1906

Hamatsa emerging from the woods by Edward S. Curtis

Editor’s Note: Native American cultures have diverse religious beliefs with various spiritual systems. Though many Native American cultures have traditional healers, ritualists, singers, mystics, lore-keepers, and Medicine people, none have ever used the term “shaman” to describe these religious leaders.

Mediators between the world of spirits and the world of men can be divided into two classes: The shamans, whose authority was entirely dependent on their individual ability, and the priests, who acted in some measure for the tribe or nation.

The Shaman is explained variously as a Persian word meaning “pagan” or, with more likelihood, as the Tungus (nomadic Mongoloid people of East Siberia) equivalent for “medicine-man,” and was originally applied to the medicine men or exorcists in Siberian tribes, from which it was extended to similar individuals among the Indian tribes of America.

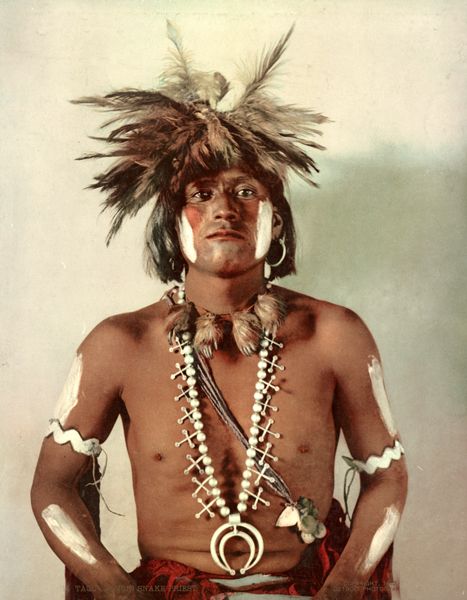

Among the Haida and Tlingit tribes, shamans performed practically all religious functions, including that of a physician. Occasionally, a shaman united the civil with religious power by being a town or house chief. Generally speaking, he obtained his position from an uncle, inheriting his spiritual helpers just as he might his material wealth; but some shamans became such owing to natural fitness.

In either case, the first intimation of his new power was given by the man falling senseless and remaining in that condition for a certain period. Elsewhere in North America, however, the sweat bath was an important assistant in bringing about the proper psychic state, and certain individuals became shamans after escaping from a stroke of lightning or the jaws of a wild beast.

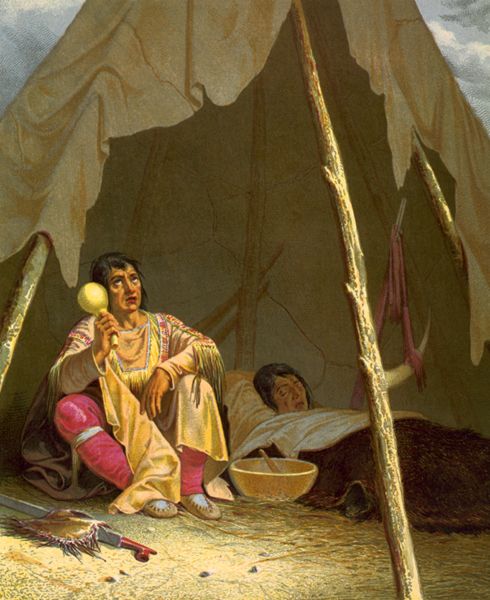

Medicine man with a patient, by Captain Eastman, C. Schussele Lithograph.

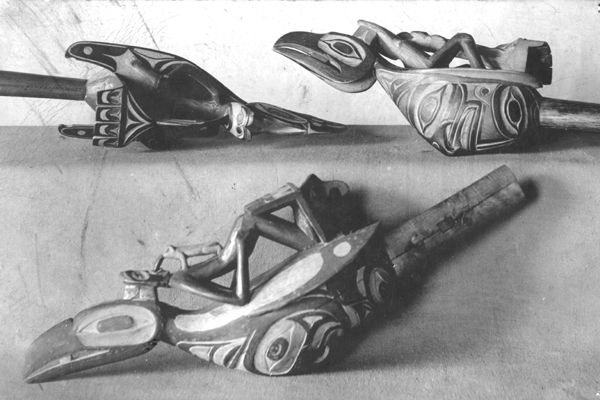

When treating a patient or otherwise performing, a northwest coast shaman was supposed to be possessed by a supernatural being whose name he bore and dress he imitated. Among the Tlingit, this spirit was often supported by several minor spirits represented upon the shaman’s mask, strengthening his eyesight, sense of smell, etc. He let his hair grow long, never cutting or dressing it. When performing, he ran around the fire very rapidly in the direction of the sun while his assistant beat upon a wooden drum, and his friends sang the spirit songs and beat upon narrow pieces of board. Then the spirit showed him what he was trying to discover, the location of a whale or other food animal, the approach of an enemy, or the cause of a patient’s sickness. In the latter case, he removed the object causing pain by blowing upon the affected part, sticking at it, or rubbing a charm. If the soul had wandered, he captured and restored it, and in case the patient had been bewitched, he revealed the offender’s name and directed how he was to be handled. Payment for his services was always made in advance, but in case of failure, it was usually returned, while among some tribes, failure was punished with death. Shamans also performed sleight-of-hand feats to show their power, and two shamans among hostile people would fight each other through the air through their spirits.

The ideas behind shamanistic practices in other American tribes were the same as these, but the forms they took varied considerably. Thus, instead of being possessed, Iroquois shamans and probably others controlled their spirits objectively as if they were handling many instruments, while Chitimacha shamans consulted their helpers in trances. Among the Nootka, there were two classes of shamans, the Ucták-u, or “workers,” who cured a person when sickness was thrown upon him by an enemy or when it entered in the shape of an insect, and the K’ok-oā’tsmaah, or “soul workers,” who were employed to restore a wandering soul to its body.

The Songish of the southern end of Vancouver Island also had two sorts of shamans. Of these, the higher, the squnä’am, acquired his power in the usual way through intercourse with supernatural beings. At the same time, the sī’oua, who was usually a woman, received her knowledge from another sī’oua. The former answered more nearly to the common type of shaman, while the latter’s function was to appease hostile powers, to whom she spoke a sacred language. She was also applied to by women who desired to bear children and for all kinds of charms.

Among the Salish, the initiation of shamans and warriors seems to have taken place similarly, i.e., through animals which became the novices’ guardian spirits. Kutenai shamans had special lodges in the camp larger than the rest, in which they prayed and invoked the spirits.

Shaman’s Rattles

The Hupa of California recognized two sorts of shamans: the dancing shamans, who determined the cause of disease and the steps necessary for recovery, and other shamans, who, after locating the trouble, removed it by sucking. Mojave shamans usually receive their powers directly from Mastamho, the chief deity, and acquire them by dreaming rather than the usual fasting methods, isolation, petition, etc. This latter feature is also among the Shasta. The Maidu seem to have presented considerable variations within one small area. In some sections, heredity played little part in determining who should become a shaman, but in the northeast part of the Maidu country, all of a shaman’s children were obliged to take up his profession, or the spirits would kill them. There were two sorts of shamans, the shaman proper, whose functions were mainly curative, and the “dreamer,” who communicated with spirits and the ghosts of the dead. All shamans were also dreamers, but not the reverse. During the winter months, the dreamers held meetings in darkened houses, where they spoke with the spirits much like modern spirit mediums. At other times the shamans of the foothill region met to see which was most powerful and danced until all, but one had dropped out. One who had not had a shaman for a parent had to go into the mountains to a place where some spirit was supposed to reside, fast, and go through certain ceremonies, and when a shaman desired to obtain more powerful helpers than those he possessed, lie did the same. Shamans in this region always carried cocoon rattles.

Historians list three classes of shamans among the Chippewa, in addition to the herbalist or doctor, properly so considered. These were the wâběnō’, who practiced medical magic; the jěs’sakī’d, who were seers and prophets deriving their power from the thunder god; and the midē,’ who were concerned with the sacred society the Midē’wiwin, and should rather be regarded as priests. These latter were represented among the Delaware by the medeu, who concerned themselves, especially with healing, while there was a separate class of diviners called powwow, or `dreamers.’ Unlike most shamans, the Central Eskimo communicated with their spirits while seated. It was their chief duty to find out the breaking of what taboos had caused sickness or storms.

As distinguished from the calling of a shaman, that of a priest was national or tribal rather than individual. If there were considerable rituals, his function might be more that of a leader in the ceremonies and keeper of the sacred myths than a direct mediator between spirits and men. Sometimes, as on the northwest coast and among the Eskimo, the functions of priest and shaman might be combined. The two terms have been used so interchangeably by writers, especially when applied to the Eastern tribes, that it is often difficult to tell which is the proper one.

Even where shamanism flourished most, there was a tendency for certain priestly functions to center around the village or tribal chief. This appears among the Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Kwakiutl in the prominent part the chiefs played in secret society performances, and the chief of the Fraser River coast Salish was even more of a high priest than a civil chief, leading his people in religious functions.

Most of the tribes of the eastern plains contained two classes of men that may be placed in this category. One of these classes consisted of societies that concerned themselves with hearing and applying definite remedies, though at the same time, invoking superior powers, and to be admitted to which a man was obliged to pass through a period of instruction. The other comprised one of the few men who acted as superior officers in the conduct of national rituals and who transmitted their knowledge concerning it to an equally limited number of successors. Similar to these, perhaps, were the priests of the Midē’wiwin ceremony among the Chippewa, Menominee, and other Algonquian tribes.

Some sources say that there was a high priest in every Creek town. These were persons of consequence and greatly influenced the state, particularly military affairs. They would foretell rain or drought, pretend to bring rain for pleasure, cure diseases, exorcise witchcraft, invoke or expel evil spirits, and even assume the power of directing thunder and lightning. The Natchez state was a theocracy in which the head chief, or “Great Sun,” was directly descended from the national lawgiver who had come out of the sun and was an ex-officio high priest of the nation. The rest of the Suns shared their functions to a minor degree and formed a sacred caste.

Doubtless, the most highly developed priesthood north of Mexico, however, was among the Pueblos of New Mexico and Arizona, where they control the civil and military branches of the tribe. The rain priesthood was a body almost entirely composed of men whose duty was to bring plentiful rain supplies by secret prayers and fasts. The priesthood of the bow was really a war society whose ceremonies were held to give thanks for abundant crops or, after a scalp had been taken, to bring about rain through the pleasure that the taking of this scalp gave to the gods, the controllers of the rain. The two head priests of the bow and the rain priests of the six cardinal points form the fountainhead of all authority and the court of the last appeal in Zuni. Each of these, except the priest of the zenith, had several assistants, and the priestess of fecundity, the female assistant of the priest of the north, who stood highest in rank, possessed great authority. Below these were the society of Kótikilli and the esoteric societies. All male Zuni and very rarely some females were admitted into the former, which dealt directly with the gods and whose ceremonials were to bring rain. The esoteric societies, however, had to do mainly with the zoic or beast gods and were primarily healing societies. They might treat a patient at the time of the ceremonies, or they may send for a single member. These societies also held very important ceremonies to bring rain. The active members of these societies, including the Kótikilli, in contradistinction to the rain and war priests, were called by a special name, “theurgists,” but their functions approached nearer to those of priests than of shamans.

By Frederick Webb Hodge, 1906. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Text from The Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico by Frederick Webb Hodge, Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office, 1906. The above text is not verbatim; it has been truncated and heavily edited.

Also See:

Medicine Wheel & the Four Directions