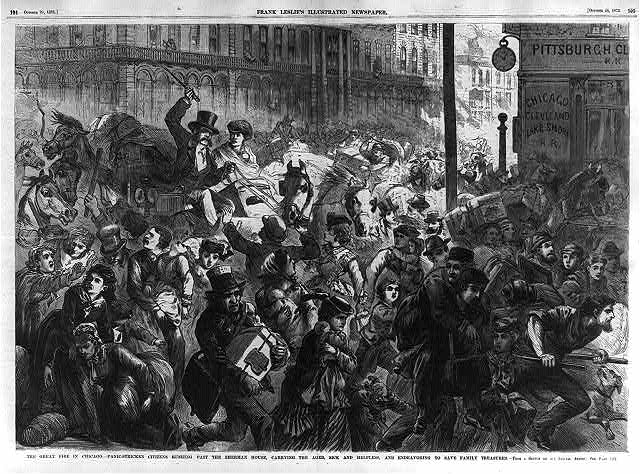

The Great Fire in Chicago – panic-stricken citizens rushing past the Sherman House, carrying the aged, sick and helpless, and endeavoring to save family treasures. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 28, 1871.

On the night of October 8, 1871, only an hour or so after the Peshtigo Firestorm began some 250 miles away in Wisconsin, the city of Chicago would see the beginnings of one of the largest disasters of the 19th Century that would leave at least 300 people dead, and destroy over 3 square miles of the city.

The conditions for the disaster that would become known as the Great Chicago Fire actually began earlier that Summer. The region was struck by drought and the ground was ready for a spark. That also meant that any wooden city, such as Chicago, was especially vulnerable.

That evening about 9 pm around a small barn behind DeKoven Street owned by Patrick and Catherine O’Leary, the fire started. Although the O’Leary’s would be widely blamed, with the common story being the O’Leary’s cow kicking over a lantern, no one really knows the exact cause of the blaze, and convergence of weather and human errors would cause it to spread.

Local firefighters, exhausted from fighting a large fire the previous day, were initially sent to the wrong neighborhood when the alarm came in. By the time they arrived at the O’Leary’s, the fire was already out of control and quickly spread east and north. A frontal system bringing high winds whipped the flames to other nearby buildings and carried hot embers toward the heart of the city.

While the fire was eating away at mansions, industrial buildings, churches, businesses and homes, at first residents didn’t realize the extent of the danger they were in. But as it continued through the city’s central business district, mass panic ensued as residents tried to flee the flames.

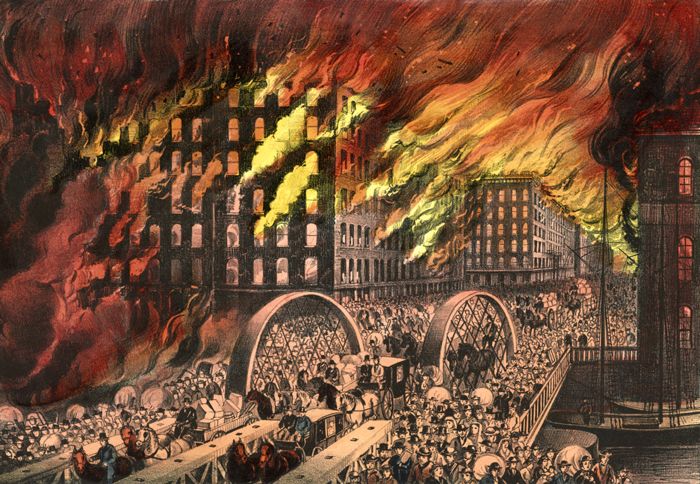

As the size of the blaze grew, it created it’s own weather, generating strong winds and heat, which is said to have ignited rooftops ahead of the actual blaze. The fire would continue for 36 hours through Monday into early Tuesday, October 10, leaving over 100,000 homeless.

At one point, the Mayor of the city, in an attempt to calm the situation, placed Chicago under martial law. This was coordinated by noted Civil War Union General Philip Sheridan. Martial law was lifted only a few days later as no widespread disturbances resulted.

The fire finally abated as the winds from the frontal system diminished and a light drizzle began falling late that Monday night. In its wake, the Great Chicago Fire destroyed an area about four miles long and averaged three-quarter mile wide. The tally of destruction included 17,450 buildings and over $220 million in property. Ironically, the O’Leary’s home was spared as the fire blew away from their home.

Chicago Fire, 1871 by Currier & Ives

News of the blaze would be headlines for weeks in Newspapers as word spread across the globe. Money and donations of food and clothing poured into the city, and it wasn’t long at all before rebuilding began. In fact, the fire is recognized as the turning point for Chicago’s early history and secured the city’s reputation as a place of opportunity, renewal, and future promise. Though the fire was spectacular, its news would overshadow a greater tragedy that started only a couple of hours before when up to 2500 people lost their lives in the Peshtigo Firestorm some 250 miles away in Wisconsin. Just like the Chicago Fire, the Peshtigo blaze was fanned by the same frontal system and is known as the deadliest blaze in United States recorded history.

In fact there were three other major fires along the shores of Lake Michigan at the same time as the Chicago fire. In addition to the Peshtigo fire to the north, across the lake to the east the town of Holland Michigan burned to the ground. And further east along the shore of Lake Huron, the Port Huron Fire destroyed another large area of Michigan. Another fire on October 9 swept through Urbana Illinois, and Windsor Ontario Canada also reported a fire on October 12.

This lead to theories about the fires being started by meteorites and yet another theory as recent as 2004 is that a comet broke up over the Midwest causing the calamity. Scientists discount those theories though, especially since meteorites are not known to cause fires and are cool to the touch after reaching the ground.

Whatever started the Great Chicago Fire, it was the same dry conditions, coupled with human error and carelessness, and a timely frontal system that set the region ablaze that October. In the aftermath, the city, and others, improved their building techniques, and Chicago quickly re-wrote its fire standards and developed one of the country’s leading fire fighting forces.

Today, near where the blaze started that night around O’Leary’s barn, stands the Chicago Fire Monument in front of the Chicago Fire Academy.

©Legends Of America, Dave Alexander – updated September 2020.

Also See:

Chicago – The Route 66 Journey Begins

Chicago’s Flapper Ghost of the Roaring Twenties

Illinois (main page)

Sources: Chicago History Museum, Library of Congress, Wikipedia.