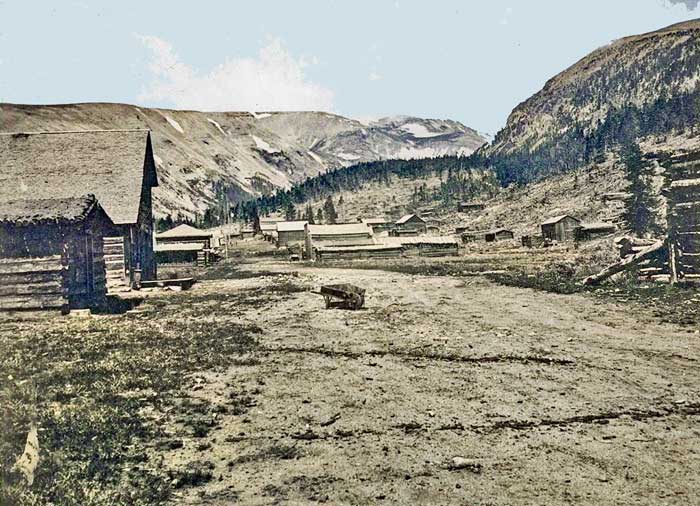

One of only two known photos of the original Buckskin Joe mining camp, taken in 1864. Touch of color by LOA.

Buckskin Joe, Colorado, also called Laurette, was a deserted ghost town that once served as the county seat of Park County, then a reborn attraction, and finally dismantled and moved to a private ranch. This once flourishing mining camp, located about two miles west of Alma, Colorado, started in 1859 when a prospector named Mr. Phillips filed a mining claim. However, he didn’t think the claim looked rich, so he soon moved on.

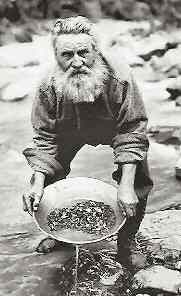

Joe Higgenbottom, the man for which the settlement of Buckskin Joe was named.

Phillips’ claim was soon taken over by Joseph Higgenbottom, who was known for wearing buckskin clothing. As more miners came to the area, the camp took on the name of “Buckskin Joe.”

Joe Higgenbottom soon traded his workings for a gun and a horse, gave up his water rights to pay a whiskey bill, and left for the mines of the San Juan Mountains.

A short time later, rich claims were discovered in the vicinity, and the news of the gold discovery quickly spread. By the spring of 1860, other miners began pouring into the mining camp. Sluice boxes were built, and considerable gold was recovered from Buckskin Creek. The old Spanish method of arrastra was employed at first, but later, a mill was built to crush the soft ore from the load. By September of 1860, all the claims in the district had been purchased, and 2,000 men were working in the area.

The mining camp then blossomed into a town. Despite some attempts to officially name the settlement Laurette, a contraction of the first names of the only two women in the camp — sisters Laura and Jeanette Dodge, it continued to be called Buckskin Joe by most, and the name stuck.

A post office opened in 1861, at which time the town boasted two hotels, 14 stores, and a bank. In August 1861, Horace and Augusta Tabor loaded their supplies, groceries, and household merchandise and moved to Buckskin Joe. Their store soon became the area’s most successful. During the next seven years, Horace invested in local mines and became the postmaster. In reality, Augusta ran the post office, although she could not legally hold that position. Meanwhile, Horace became increasingly involved in community affairs.

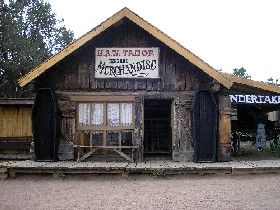

Tabor’s Old Store, Buckskin Joe, Colorado

Buckskin Joe had itinerant preachers, Father John L Dyer, a Methodist from Ohio whose circuit covered Fairplay, Park City, Buckskin Joe, and Breckenridge. To stretch parishioners’ contributions in the early days, Dyer would prospect when not in the pulpit. As accessible placer findings vanished and the cost of staples soared ($40.00 for a bag of flour), Dyer added mail-carrying to his church duties. He trekked weekly from Mosquito Gulch and Buckskin Joe over passes to Leadville and Breckenridge. Neither winter nor the absence of improved roads deterred him. Often on skis ten feet long with 30 pounds of mail on his back, Father Dyer would climb through deep snow and wind-swept alpine heights to dispense his earthly and spiritual messages.

In January 1862, the Park County Seat moved from Tarryall, now also a ghost town, to Buckskin Joe.

Though the gold deposits were rich in the area, they mostly played out by 1866. The courthouse building was moved down the valley to the new county seat of Fairplay in 1967. At its zenith, the town of Buckskin Joe sported some 3,000 people and several saloons, gambling halls, and traveling minstrel shows. The street was lined with stores, a post office, an assay office, a courthouse, two banks, a newspaper, a mill, and three hotels.

Buckskin Joe Hotel and Dance Hall

The mining district reportedly produced 16 million dollars in gold from 1859 until the mill closed in 1866. After the mill closed, most people left to seek their fortune in other mining camps and towns throughout the Rocky Mountains.

A few stalwarts remained. One was J.P. Stansell, who made a fortune working the residue of the Phillips Mine long after the others left. Another was Horace Tabor, who would later make his fortune in Leadville.

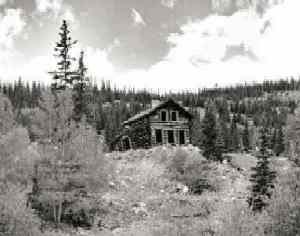

All that is left of the original Buckskin Joe today is the cemetery and its memories. Close inspection of the tombstone dates reveals a cemetery population boom in 1861 and 1862. The cemetery, which is down the road on the right from the old settlement site, also reveals the struggles of the miners and settlers. The stone grave of young Thomas Fahey records that he left his cabin on a blustery February day to go to his mine and did not return. His body was found the following June.

Many of the miners were immigrants from Europe. Images of home and echoes of their languages can be seen on some stones. The stones and gravesites with their ornate rails and gates exhibit a craft and workmanship that outlasted the modest cabins and other structures in the town. The town of Alma still uses the cemetery.

The site of old Buckskin Joe is located northwest of Fairplay, Colorado, on Highway 9, near the present-day town of Alma, Colorado.

The Legend of Silver Heels

A local hero and legend emerged in Buckskin Joe in 1861 — a dance hall girl named “Silver Heels.” From the day she stepped off the stagecoach at the mining camp, her beauty captivated the entire mining camp. Her real name was never known, for the miners had long since dubbed her “Silver Heels,” perhaps for her dance shoes or enchanting performances. In any event, the beloved Silver Heels prepared to travel on after a few nightly performances, but when the miners showered her with gifts and begged her to stay, she agreed.

In the winter of 1861, the deadly disease smallpox invaded the mining camp. The epidemic swept through the town, and miners and families became very ill almost overnight. Within days, the rutted dirt road to the cemetery became lined with the living carrying the dead up the hillside for burial. The citizens of Buckskin Joe sent to Denver for nurses, but none came. All who could help did so, including Silver Heels. Especially Silver Heels.

All through the deadly horror of the smallpox explosion, Silver Heels stayed in cabin after cabin, nursing the sick, caring for the families, burying the dead. By the spring of 1862, the worst was over, at least for the mining camp of Buckskin Joe. In the aftermath, Silver Heels had vanished. The surviving miners searched the entire mountain area. Her cabin was clean, yet she was gone. She had not left by stage or horse. Some say she, herself, had contracted smallpox, leaving her once beautiful face horribly scarred. A few years later, it was said that a heavily veiled woman was seen in the Buckskin Joe cemetery that many thought might have been the missing Silver Heels.

Miners in Buckskin Joe in the 1890s

The area’s people named a mountain “Mount Silver Heels” in gratitude to this brave woman.

Legend has it that Silver Heels has never left. Several members of the community claim to have seen the ghost-like presence of a heavily veiled woman, dressed all in black, walking through the cemetery. Carrying flowers, the once-beautiful Silver Heels has been seen, and her presence felt for over a century. The ghost is said to vanish into the mountain air if approached. Once so beautiful, but then scarred, she was still loved; she just didn’t know it.

Another restless spirit is said to inhabit the bones of J. Dawson Hidgepath. The man came to Fairplay to find gold and a wife but instead found tragedy. In July 1865, Dawson’s broken, lifeless body was found at the bottom of the west side of Mount Boss, where he had fallen several hundred feet while trying to prospect for gold on the mountainside.

Soon after his burial, Dawson’s bones were discovered on the bed of a prostitute in the town of Alma. Believing a tasteless prank had taken place, townspeople reburied the bones in Buckskin Joe Cemetery. Nevertheless, time after time again, the bones showed up at the house of some “fair lady.” By 1872, Dawson’s bones were the talk of the state, and people were throwing them down outhouses to get rid of them. What went on is almost impossible to determine today, but whatever “force” kept Dawson’s bones from staying buried is said to still reside in the old cemetery.

The New Buckskin Joe

In the 1950s, Karol Smith desired to restore Buckskin Joe but did not find the people he needed to help him in his effort until sometime around 1957. It was at this time that he met Don Tyner and Malcolm F. Brown. Brown was an art director at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, and Tyner was the owner of the Royal Gorge Scenic Railway. Each was interested in the rebuilding of Buckskin Joe. It was decided the rebirth of the mining city would take place next door to the Royal Gorge Scenic Railway. At that time, investors purchased land approximately eight miles east of Cañon City, where the town of Buckskin Joe was recreated.

Each building and structure represented the actual buildings from the original town of Buckskin Joe, and all were original buildings from various ghost towns in the region. The Tabor store building was moved there from the original town of Buckskin Joe. It was the last remaining building at the original townsite. Each structure was acquired and dismantled at its original site, transported to the new site, and reassembled. Each structure was chosen to represent a different type of building, such as a saloon or a jail. The main townsite is a long street with another street heading at right angles between the main street and the Royal Gorge Railroad.

The new Buckskin Joe opened in 1958 to the general public. In each case, an effort was made to maintain the atmosphere of a mining town in the mid-1800s. No modern vehicles were permitted on the streets, and the inhabitants’ dress was like that worn in the “good old days.”

Until 2010, the spirit of the Old West exploded to life at Buckskin Joe Frontier Town & Railway. The park combined actual Colorado history with family entertainment, creating a truly unique experience. This authentic old west town was brought to life with hourly gunfights, some historical and humorous, exciting live entertainment, barnyard animals for the kids, numerous buggies and wagons, and one Concord type stagecoach. John Wayne was shooting movies here in the early 1970s, and as recently as 2001, the History Channel was filming a documentary entitled “The Haunted Rockies” on location.

After 53 years of operation, owner Greg Tabuteau announced in the summer of 2010 that he was selling the tourist attraction. In August of 2011, it was revealed that the buyer was Billionaire William Koch, who moved most of the buildings to his 6,400 acre Bear Ranch near Gunnison, Colorado. Bill Koch, a Florida billionaire, loves Old West memorabilia and planned to display his collection in the reassembled buildings on his ranch for private viewing only by friends and family. One of the buildings moved to his ranch was the Tabor Store, which once stood in the original Buckskin Joe in Park County.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See:

The Argonauts and the Founding of Denver

Colorado Ghost Towns Photo Galleries

Bear Ranch, by Devon Meyers for Aspen Journalism

Ghost Towns & Mining Camps of Colorado

Pike’s Peak Gold Rush and Colorado Territory

Sources:

Ute Pass Historical Society

Westword

Wikipedia

Wolle, Muriel Sibell, Stampede to Timberline; Aircraft Press, Denver, Colorado, 1850.