William Clark was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor who, along with Meriwether Lewis, led the Corps of Discovery Expedition of 1804–1806.

Born on August 1, 1770, in Caroline County, Virginia, William Clark was the ninth of ten children born to John Clark, III, and Ann Rogers. His parents were common planters of modest means, and Clark received no formal education. Instead, he was taught at home but grew up to be self-conscious about his grammar and inconsistent spelling. His five older brothers fought in Virginia units during the American Revolutionary War. His oldest brother, Jonathan Clark, served as a colonel during the war and later rose to brigadier general in the Virginia Militia. His second-oldest brother, George Rogers Clark, rose to the rank of general, spending most of the war in Kentucky fighting against British-allied American Indians.

In March 1785, Clark moved to Kentucky with his parents and three sisters, settling near Louisville. There, his older brother George Rogers Clark taught William wilderness survival skills. In 1789, he enlisted in the army and was stationed in the Ohio Valley, which protected the Kentucky settlements from Indian attacks. In 1791, he fought against the Indians under General Charles Scott’s command in the Battle of the Wabash in present-day Ohio — part of the Northwest Indian War. He was lucky to have survived, as the conflict was one of the worst defeats in the percentage of casualties ever suffered by the United States Army. It was also the most significant victory ever won by American Indians.

He was transferred to General Anthony Wayne’s unit four years later and was named Lieutenant in command of the fourth brigade. Meriwether Lewis was later placed in the unit under Clark’s command, and the two developed a deep friendship and respect for each other. After serving in the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, he left the Army and returned to his family. A few years later, his father died, and Clark inherited a large amount of land and some slaves, including a man named York, whom Clark had known since childhood. During those years, Clark also met and married Julia Hancock.

In the meantime, Meriwether Lewis continued his military career and served as President Thomas Jefferson’s private secretary. In mid-1803, after Congress had approved a wilderness expedition that had been a pet project of Lewis’s since 1792, William received Lewis’s invitation to co-captain the expedition. Clark eagerly accepted, bringing along his childhood friend and slave, York. Although Lewis and Clark believed they would share the Expedition captaincy, the word that Clark would remain a lieutenant arrived shortly before they departed St. Louis, Missouri. The men of the Expedition, called the Corps of Discovery, having spent a winter addressing “Captain Clark,” were not told of the difference between their two leaders.

They and their men explored the vast uncharted area newly acquired in the Louisiana Purchase for the next three years. William Clark’s contributions to the Expedition were those of a captain. The map he created as they traveled was, at the time, the most accurate map of the trans-Missouri West. His stable personality balanced Lewis’s moodiness. And when Lewis’ pen fell silent during many months of the journey, Clark’s straightforward and creatively spelled words became the Expedition record.

William Clark also left his mark along the Trail. On July 25, 1806, Clark scratched his signature into a sandstone formation along the Yellowstone River in Montana. Recording the event in his journal, Clark noted that “this rock I ascended … had a most extensive view in every direction…I marked my name and the day of the month and year.” He called the formation Pompey’s Tower, using a nickname Clark had bestowed on Sacagawea’s son Jean Baptiste, or Pomp. The etched signature is still seen at the site, now called Pompeys Pillar, near Billings, Montana. Clark’s signature is believed to be the only remaining on-site physical evidence of the expedition.

Having crossed a continent, Clark returned to St. Louis to build a successful and varied family and work life. For his success in the expedition, President Jefferson awarded him 1,600 acres and made him a brigadier general of militia for the Louisiana Territory and superintendent of Indian affairs. In addition to fathering seven children, William Clark temporarily cared for Sacagawea’s son, Jean Baptiste. After Lewis’s death, Clark completed the Expedition work by helping to prepare the journals for publication. Clark’s fair diplomatic relations with American Indians during his years as brigadier general of the militia and Superintendent of Indian Affairs helped him obtain the governorship of Missouri Territory, which he held from 1813 to 1832. Clark died of natural causes in St. Louis on September 1, 1838, and is buried in the Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

One hundred sixty-three years after his death, William Clark received a promotion. In 2001, President Clinton promoted Clark from Lieutenant to Captain. Although Clark’s captaincy was late in coming, in having called the famous journey of 1803 to 1806, the Lewis Expedition would have been inaccurate in spirit, if not in fact. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark shared equally in the tasks and responsibilities of their cross-continental journey.

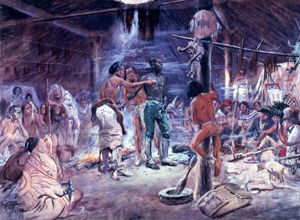

Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, Clark’s slave, York, visits Indians on the Corps of Discovery Expedition. Painting by Charles M. Russell, 1908.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Corps of Discovery – The Lewis & Clark Expedition

Sources:

Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail

University of Virginia

Wikipedia