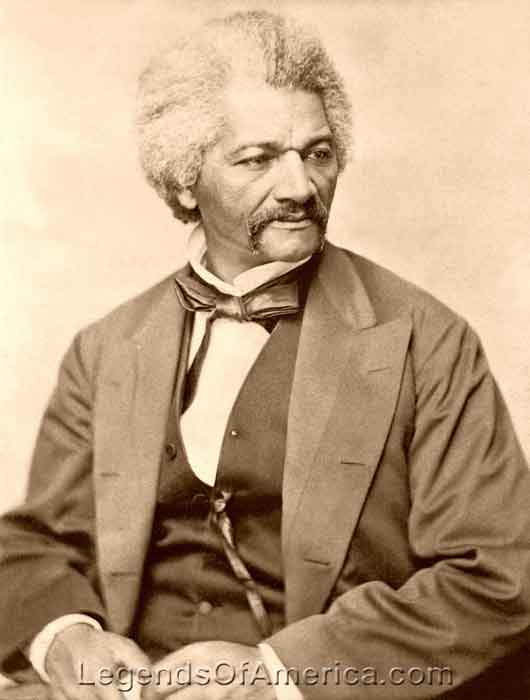

Frederick Douglass was born on a plantation on the Eastern Shore of Maryland around 1818. He died 77 years later in his home at Cedar Hill, high above Washington, D.C. In his journey from captive slave to internationally renowned activist, Douglass changed how Americans thought about race, slavery, and American democracy. Since the early 1800s, Douglass’ life has been a source of inspiration and hope for millions. He has also been an ever-present challenge, demanding that American citizens live up to their highest ideals and make the United States a land of liberty and equality for all.

Slavery and Escape

Douglass began his life on a plantation belonging to Edward Lloyd in February 1818. While the exact date of his birth is unknown, he would later decide to make February 14 his birthday. He was named Frederick Bailey after his mother, though he only met her three or four times in his life. After being sent to live with one of his owner’s relatives in Baltimore, Maryland, around the age of eight, Douglass was mistakenly taught the first several letters of the alphabet. Those few letters opened a new world to him and began his lifelong love of language.

At 15, the now literate Douglass was returned to the Eastern shore to work as a field hand. Here, the increasingly independent teenager educated other slaves, resisted efforts to beat him, and planned a failed escape attempt.

Three years later, on September 3, 1838, Douglass disguised himself as a sailor and boarded a northbound train from Baltimore carrying a friend’s passport. He arrived in New York City, New York, and declared himself a free man.

Abolition Work

After escaping from slavery, Douglass changed his name to avoid being recaptured and turned his efforts to helping those still held in bondage. He traveled around Massachusetts, discussing his experiences with slavery and the need to destroy it. One of the most prominent abolitionists in America, William Lloyd Garrison, heard Douglass and invited him to join the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass soon traveled across the country, speaking against slavery and becoming one of the country’s finest orators.

Douglass was such an impressive speaker who broke many of his audiences’ preconceptions that some people began to doubt he was a fugitive slave. To prove them wrong, Douglass wrote his first autobiography, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, in 1845, revealing his original name, owner’s name, and where he was born. The book was wildly popular, but Douglass was in danger of being returned to slavery with his identity known. Once again, he had to flee, this time to Great Britain.

While in the British Isles, Douglass continued speaking against slavery. British supporters were so impressed with Douglass that they purchased his freedom. After more than two years abroad, Douglass returned to the United States as a legally free man. He settled in Rochester, New York, a hotbed of the abolitionist and women’s rights movements. Using additional money raised in Britain, Douglass bought a printing press and began publishing The North Star newspaper. He now proudly referred to himself as “Mr. Editor.”

Civil War

Re-enactors fire cannons during the 149th Anniversary of the Battle of

Chickamauga, Georgia. Photo by Dave Alexander.

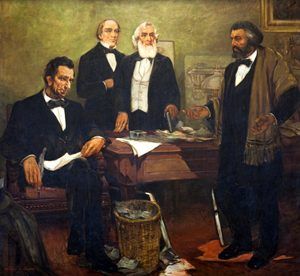

In 1861, tensions over slavery erupted into the Civil War. Douglass welcomed the conflict as the cataclysmic event needed to wipe slavery from America. He acted as the nation’s conscience, arguing that the war was about more than union and state rights. It was, he said, about a new birth of freedom, a significant step towards the promise of the Declaration of Independence.

Douglass knew this new freedom had to be won on and off the battlefield. Though he was too old to serve in battle, he recruited other African Americans to fight in the Union Army, including two of his sons, who served with the famous 54th Massachusetts. Away from the fighting, Douglass continued to write and speak against slavery, arguing for a higher purpose to the war.

He met with President Abraham Lincoln to advocate for African American troops and to encourage Lincoln to see the war as a chance to transform the country into a more perfect nation. Douglass’ influence was crucial to Lincoln’s evolution as a thinker throughout the war. Historians have called Douglass the “godfather” of the Gettysburg Address and Lincoln’s second inaugural speech.

Post Civil War

Following the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, new possibilities opened up for Douglass. He moved from Rochester to Washington, D.C., eventually buying a home at Cedar Hill. During this time, he served as the U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia, the District’s Registrar of Deeds, the U.S. Minister to Haiti, and Charge d’Affairs to the Dominican Republic. Despite his victories and successes, Douglass still had many battles to fight. African Americans’ hold on their newly won civil rights remained tenuous, and women were still not allowed to vote. He continued to work to expand civil rights in the country until he died in 1895.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

African-Americans – From Slavery to Equality

The Underground Railroad – Flight to Freedom

“Riding” on the Underground Railroad

African American History in the United States

Source: National Park Service